Who are Russians, according to Russian writers?

A historical anecdote from the 19th century has survived to this day. It's unknown how close it is to the truth, but it helps us to better define Russian nationality.

It goes like this: Once, at a court ball, Emperor Nicholas I asked Frenchman Marquis de Custine, who was a guest in Russia at the time (and who also wrote a book about his time in the country):

“Marquis, what do you think, how many Russians are in this hall?”

“Everyone, except for me and the foreign ambassadors, Your Majesty!”

“You are mistaken. This close associate of mine is a Pole, that one is a German. Over there stand two generals – they are Georgians. This courtier is a Tatar, here is a Finn and there is a baptized Jew.”

“Then, where are the Russians?” Custine asked.

“All of them together are the Russians,” Nicholas I replied.

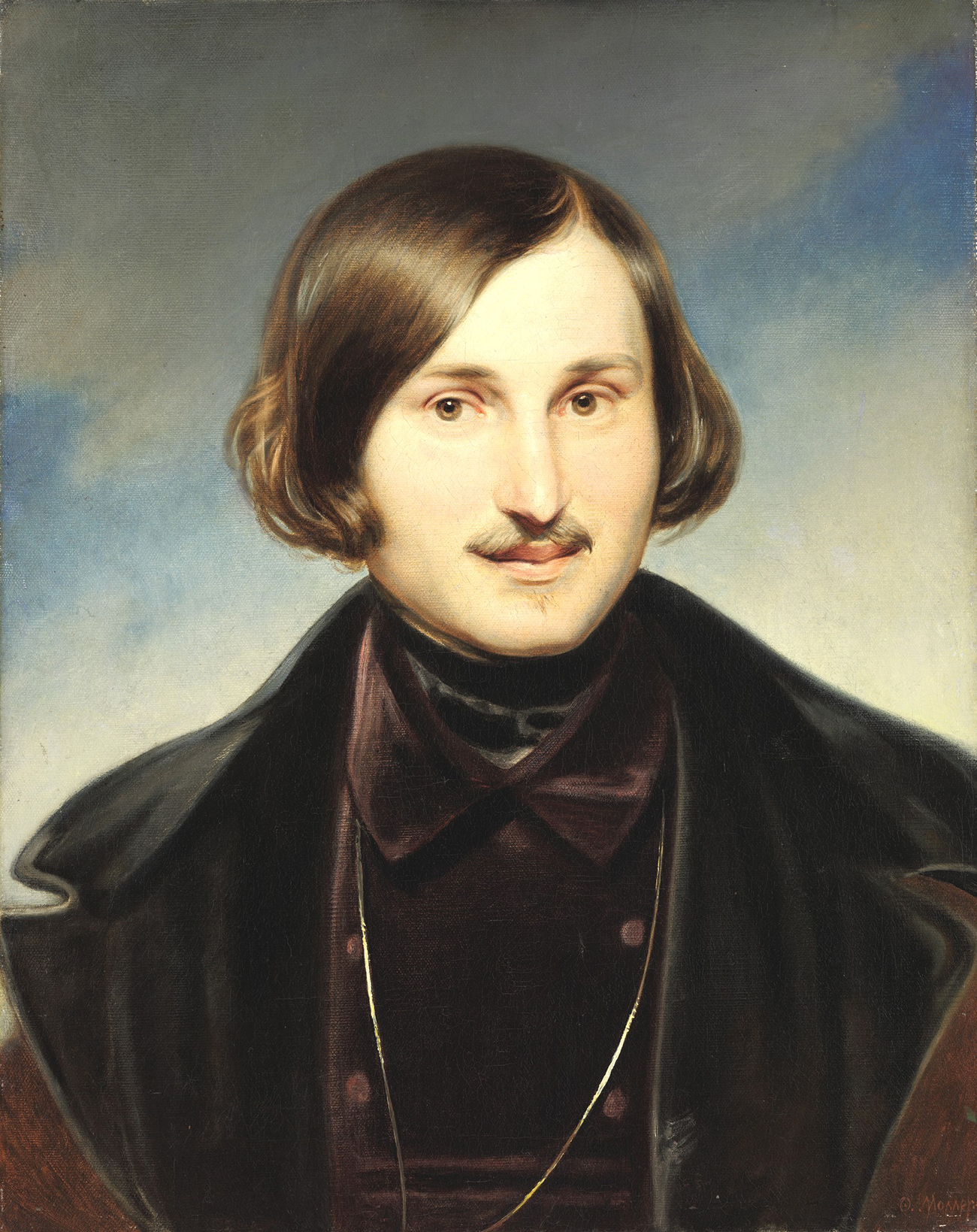

Nikolai Gogol: On the soaring Russian soul

Nikolai Gogol defined the genre of his novel ‘Dead Souls’ as a poem. And, indeed, we see numerous lyrical digressions and reflections on the nature of the Russian person and the fate of Russia itself, which gave rise to famous expressions like: “Whither, then, are you speeding, O Russia of mine?”

“For what Russian does not love to drive fast? Which of us does not, at times, yearn to give his horses their freedom and to let them go and to cry, ‘To the devil with the world!’? At such moments, a great force seems to uplift one as on wings; and one flies and everything else flies,” wrote Gogol about the Russian soul in ‘Dead Souls’.

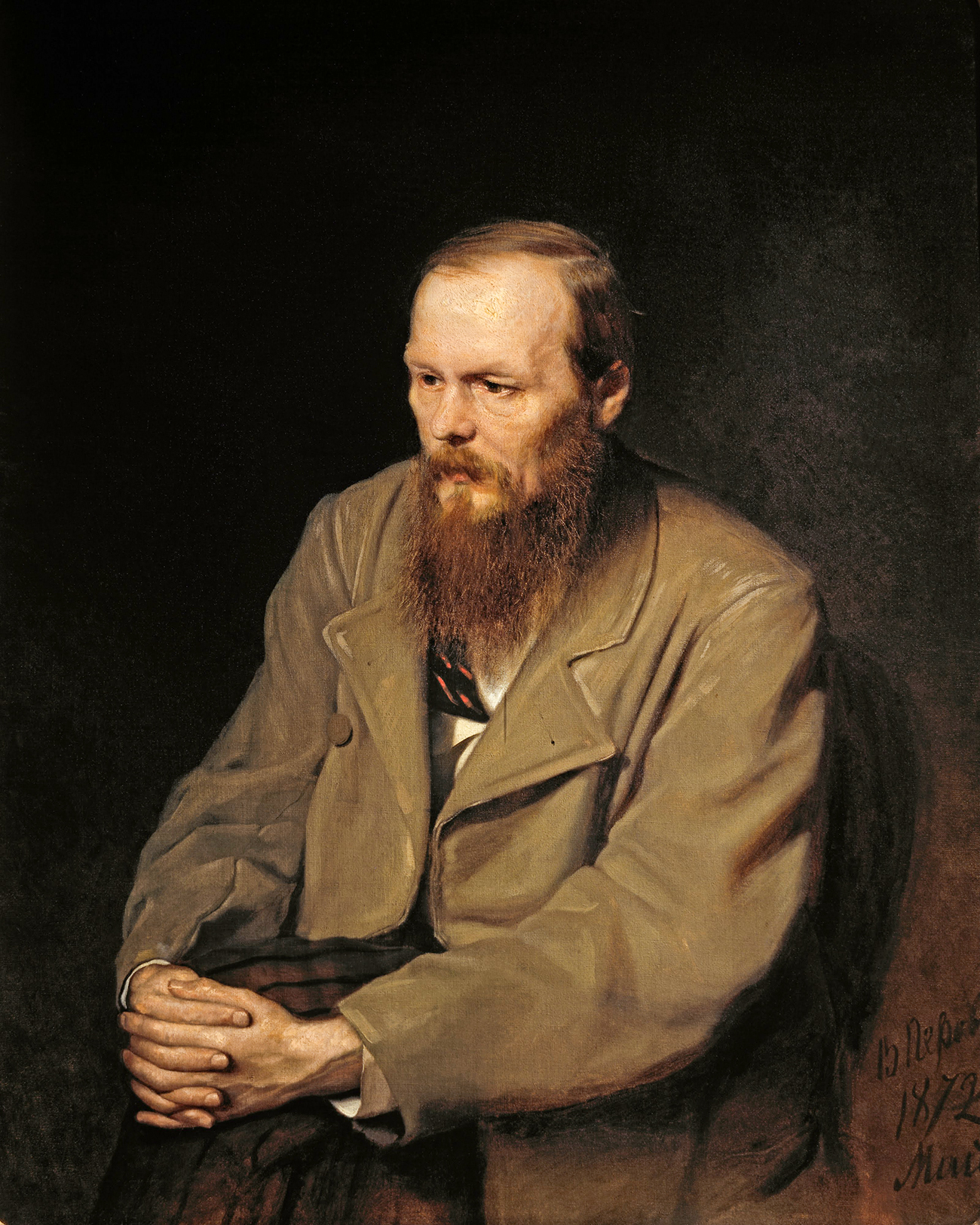

Fyodor Dostoevsky: Russians can get along with anyone

“The Russian nation is an extraordinary phenomenon in the history of all mankind. The character of the Russian people is so unlike the characters of all other contemporary European nations that Europeans still don’t understand it and misunderstand everything about it…” mused Fyodor Dostoevsky in one of his philosophical articles on Russian literature.

Dostoevsky speaks of the Russian capacity for “universal reconciliation” and “all-humanity”.

“In the Russian person, there is no European angularity, impenetrability or inflexibility. He gets along with everyone and adapts to everything. He sympathizes with everything human, regardless of nationality, blood or soil.”

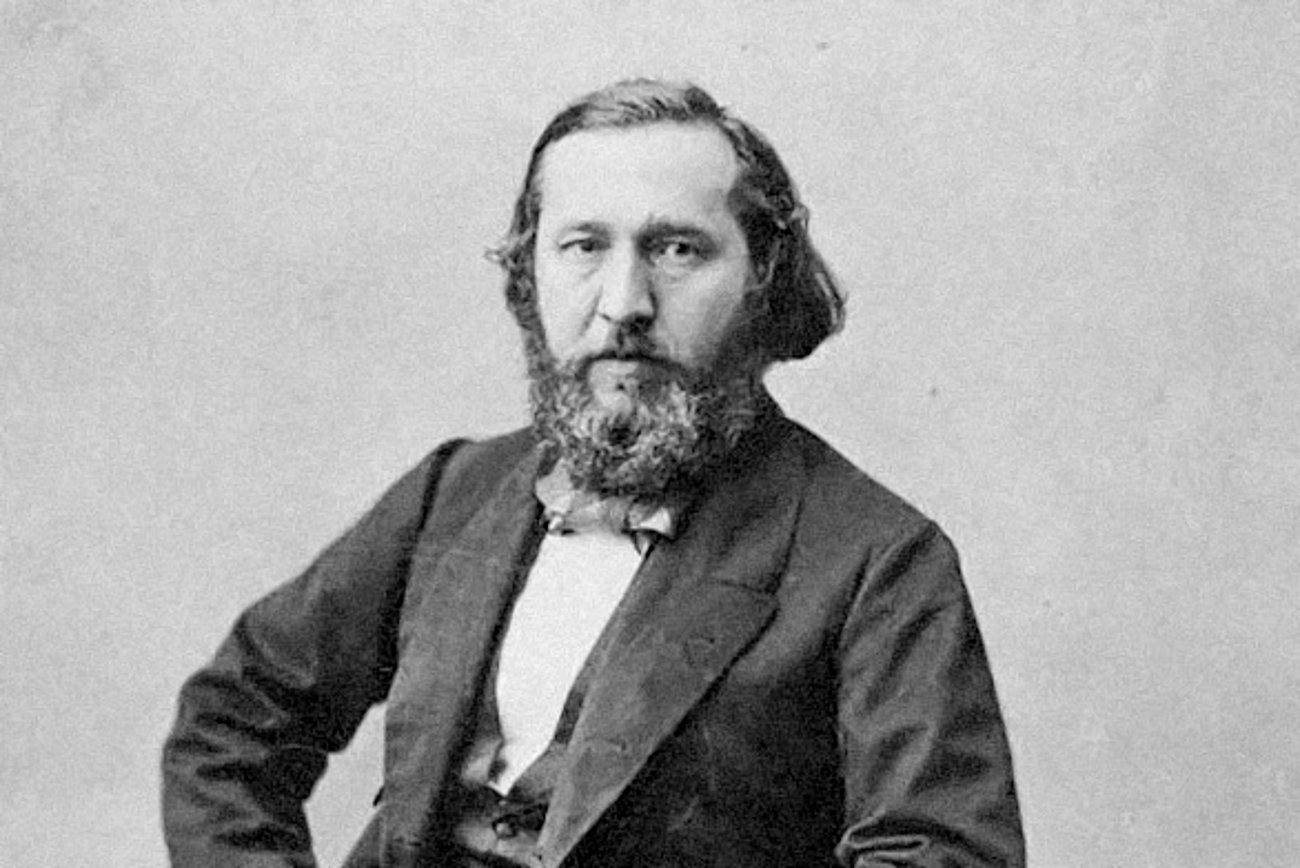

Ivan Turgenev: The strength of Russians is in their language!

“On days of doubt, days of mulling over stories and destiny of my native country, you are the only encouragement and support to me, oh, great and mighty, free and sincere Russian language!” wrote Ivan Turgenev in his prose poem ‘The Russian Language’.

“If you had not been there, how would it be possible for me not to despair on seeing what is being done at home? Still, it cannot be believed that such a language has not been given to a great nation!”

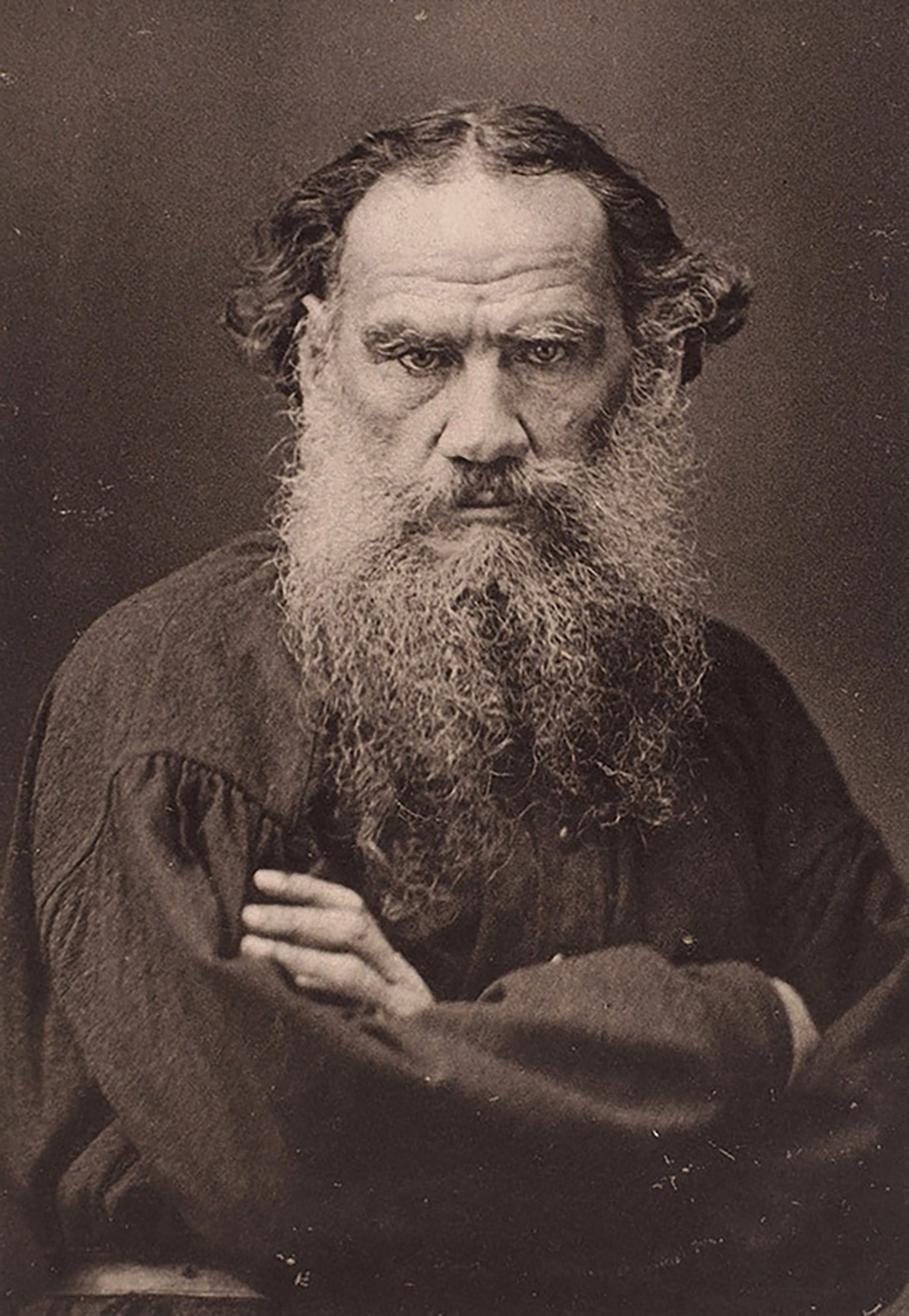

Leo Tolstoy on the profound faith of the people

“From time immemorial, an unofficial, vigorous faith has persisted among the Russian people alongside the official faith. By some strange means, it has become deeply rooted among the people, in their sayings, tales and legends, disseminated through the holy lives of the elders, the holy fools and the wanderers (‘startsy’, ‘iurodivye’, ‘stranniki’),” wrote Leo Tolstoy in his pamphlet ‘Thou Shalt Not Kill’.

“The essence of this faith is that a person should live godly, for the soul, that all people are brothers, that what is great for people is an abomination for God, that a person can be saved not by performing rituals and prayers, but only by works of mercy and love. This faith has always lived among the people and was their true faith, guiding their lives alongside the false church faith that was externally instilled in them."

Konstantin Aksakov: On freedom

“The Russian people is not a people; it’s humanity,” noted Slavophile writer Konstantin Aksakov.

“The Russian people is not a people concerned with government. That is to say, it has no aspiration toward self-government, no desire for political rights and not so much as a trace of lust for power.”

Alexei Tolstoy: On the strength of the Russian character

Soviet writer Alexei Nikolayevich Tolstoy (a distant relative of the author of ‘War and Peace’) dedicated a short story to the Russian character.

Admitting that it was a concept too profound to be easily defined, he tried to describe it and gave an example of a simple peasant who had been through war. He’s from a village, handsome and built like a ‘god of war’, yet with a radiant smile. His father had once told him, “You, my son, will see a lot in life and will visit foreign parts, but, remember always to be proud that you're a Russian!”

During the war, the hero’s face is severely burned and, after several operations, he becomes unrecognizable. His parents and fiancée no longer recognize him and he’s too ashamed to reveal himself, so he pretends to be someone else. But, later, in a letter, he confesses that it was him. Then, his fiancée visits his unit and swears to love him forever, even as he is.

“Yes, there you have them, the Russian characters! A man seems quite ordinary, until grim fate knocks at his door and a great power surges up within him – the power of human beauty,” the narrator concludes.