How did the socialist bloc react to de-Stalinization?

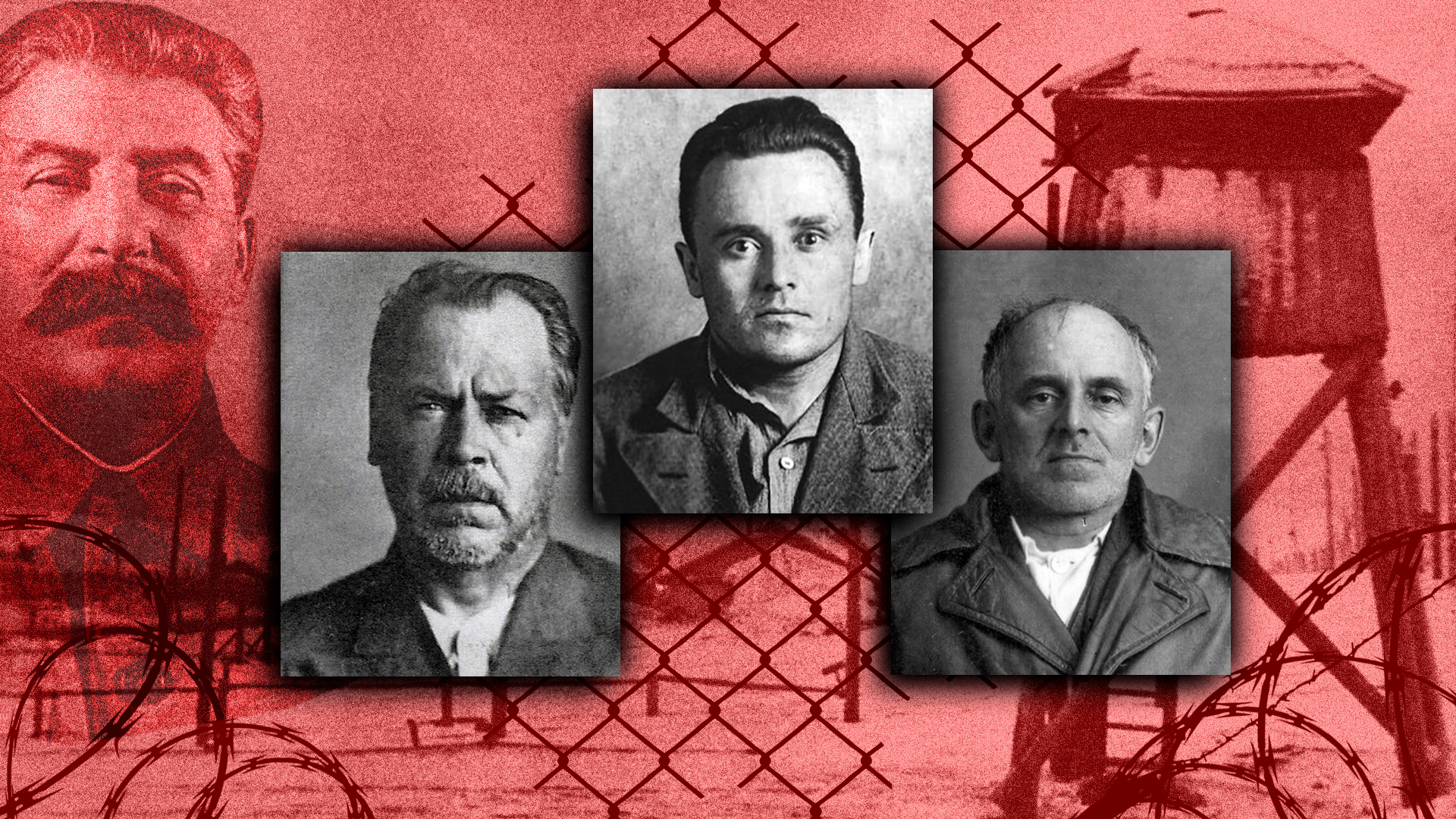

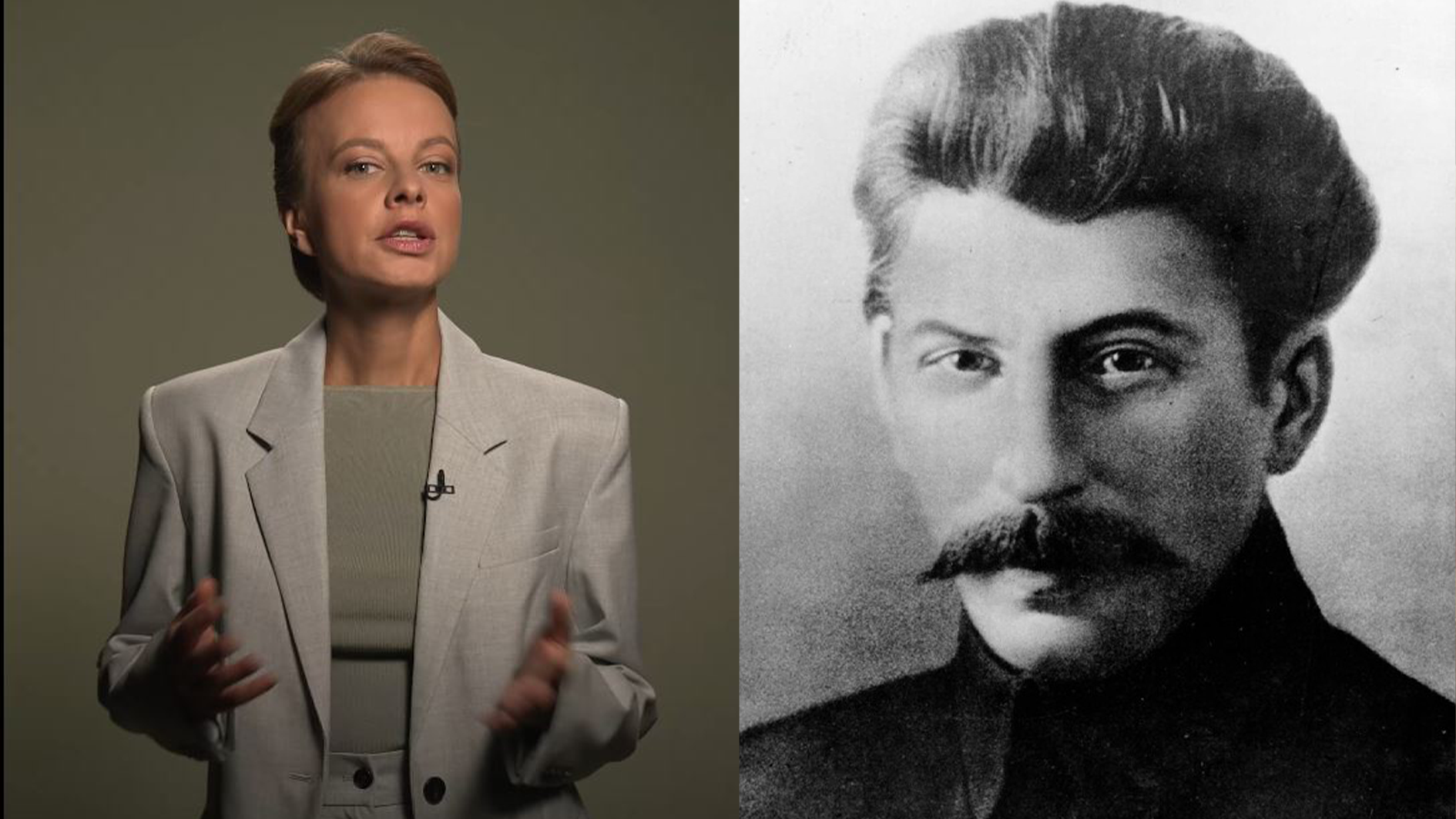

At the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in February 1956, Nikita Khrushchev publicly condemned Stalin's cult of personality and placed all responsibility for the mass terror of the late 1930s – early 1950s on the ‘Father of the Nations’.

The country began restructuring the socio-political system, which was accompanied by a partial liberalization of public life. The authorities rehabilitated the repressed, renamed metro stations, factories and cities named after Stalin, tore down monuments…

De-Stalinization directly also affected the USSR's allies in the Eastern Bloc. However, not everyone was delighted.

Hungary

A crowd of people surround the demolished head of a statue of Josef Stalin, including Daniel Sego, the man who cut off the head, during the Hungarian Revolt, Budapest, Hungary.

A crowd of people surround the demolished head of a statue of Josef Stalin, including Daniel Sego, the man who cut off the head, during the Hungarian Revolt, Budapest, Hungary.

The political struggle between the Stalinists and their opponents in the Hungarian leadership began after Stalin's death in 1953 and intensified after the 20th Congress in Moscow. In July 1956, under pressure from Khrushchev, Matyas Rakosi, the leader of the ruling Hungarian Workers' Party and a supporter of maintaining the previous course, resigned.

However, tensions in the country remained. De-Stalinization led to the growth of anti-Soviet and anti-Russian sentiments in society, calls for radical reforms and demands for the withdrawal of Soviet troops were heard.

In October 1956, an armed anti-Soviet uprising began in the country, during which one of the largest monuments to Stalin in Eastern Europe was destroyed in Budapest. But, by November, the uprising had been suppressed by Soviet troops.

East Germany

Nikita Khrushchev visits the GDR.

Nikita Khrushchev visits the GDR.

East German leader Walter Ulbrich attended the 20th Congress and fully supported the course chosen by Khrushchev. At the same time, part of the society and political elite of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) spoke out against it.

After the outbreak of the Hungarian Uprising, the number of Stalinists in East German society decreased significantly and anti-Russian sentiments openly began to grow. In response, the ruling Socialist Unity Party of Germany expanded the powers of the police and the Stasi security service and carried out a series of arrests among students and intellectuals throughout the country.

The GDR leadership rejected the liberalization of public life that was supposed to accompany de-Stalinization.

Poland

Protests in Poznan, 1956.

Protests in Poznan, 1956.

In Poland, political discussions quickly turned into demonstrations and rallies, where anti-communist slogans were heard. The culmination was the Poznan workers' uprising in June 1956, which resulted in dozens of casualties.

In October, as a result of political struggle within the ruling Polish United Workers' Party, Władysław Gomułka came to power, a figure approved by Moscow. The ‘Gomułka thaw’ was, in many ways, similar to Khrushchev's – the “liberalization of public life” took place under the strict control of the authorities.

Thus, in December 1956, a Polish analogue of the Soviet OMON was created to suppress protests - the ZOMO special forces. Already the following year, it was actively used to disperse demonstrations in Warsaw, Lodz and Rzeszow.

Romania

Romanian leader Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej (front row, left) seeing off Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in Bucharest.

Romanian leader Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej (front row, left) seeing off Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in Bucharest.

Unlike Poland, the Stalinists in Romania retained power. Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, the first secretary of the Romanian Workers' Party, supported the suppression of the uprising in Hungary and managed to build good relations with Khrushchev.

At the same time, he opposed overcoming the cult of Stalin's personality and, at the first stages, carried out de-Stalinization in an extremely limited manner. It was only in the 1960s that the country began to massively rename objects named after the ‘Father of nations’.

Czechoslovakia

Monument to Stalin in Prague.

Monument to Stalin in Prague.

There were no deep social upheavals in Czechoslovakia. Shortly before the 20th Congress, the largest monument to Stalin outside the USSR was unveiled in Prague, and it was dismantled only in 1962.

President Antonin Novotny was extremely reluctant to take measures to soften the regime. Being involved in local repressions of the 1950s, he delayed the rehabilitation of many convicted figures.

Gradually, the conservative policy of the authorities began to cause increasing discontent in society, which led to the political crisis of 1968 and the events of the ‘Prague Spring’.

Bulgaria

Todor Zhivkov.

Todor Zhivkov.

The 20th Congress in Moscow directly influenced the change of power in Bulgaria. In April 1956, the country's leader Valko Chervenkov, nicknamed ‘Little Stalin’, was dismissed.

Todor Zhivkov, who took the helm, initiated a review of the cases of the repressed. And, in 1956, Stalin, the largest port in Bulgaria, was renamed ‘Varna’.

But, liberalization in the country was carried out under strict control of the authorities. Bulgaria tried to act in line with Moscow's policies and remained the most reliable and stable ally of the USSR until the mid-1980s.

Albania

Stalin and Enver Hoxha in Moscow.

Stalin and Enver Hoxha in Moscow.

In small Albania, the story provoked a harsh response from ruler Enver Hoxha. He saw a threat both to himself and to the entire communist world.

Hoxha dealt with the opposition that accused him of being a leader and openly opposed the policies pursued by Khrushchev. The country not only did not get rid of Stalin's name, but even established an order in his honor, while the city of Kuçova bore the name of the former Soviet leader until 1990.

China

Mao Zedong and Nikita Khrushchev in Beijing.

Mao Zedong and Nikita Khrushchev in Beijing.

China also condemned it. Hoxha and Premier of the State Council of the People's Republic of China Zhou Enlai even left the 20th Congress before it closed.

De-Stalinization became one of the main reasons for the Soviet-Chinese split that began in the late 1950s. Khrushchev openly accused Mao Zedong of a cult of personality and called him "the new Stalin", putting only negative connotations into this definition.

At the same time, Chinese authorities even initiated some liberalization in the country, but it did not last long.

North Korea

Residents of the North Korean capital of Pyongyang, are shown lining one of the main thoroughfares waving a happy greeting to U.N. troops as they entered the city, 1950.

Residents of the North Korean capital of Pyongyang, are shown lining one of the main thoroughfares waving a happy greeting to U.N. troops as they entered the city, 1950.

In the DPRK, attempts were made to remove Kim Il Sung from power. The internal party struggle ended in favor of the ruling leader, which led to the beginning of mass repressions in the country. The Stalinist system in North Korea not only did not weaken, but also strengthened in the form of the state ideology of ‘Juche’ – communism with a nationalistic bias and a pronounced cult of personality of the leader.

Mongolia

Statue of Stalin that formerly decorated the entrance to the National Library.

Statue of Stalin that formerly decorated the entrance to the National Library.

De-Stalinization manifested itself in the debunking of the cult of personality of Marshal Khorloogiin Choibalsan, the country's leader, who died in 1952. However, this process was extremely moderate: they noted the “mistakes” made during his rule, but they did not demolish monuments nor did they remove his body from the mausoleum in Ulaanbaatar (this happened only in 2005)

Stalin himself also avoided condemnation. Khrushchev's repeated requests to demolish his monument in the Mongolian capital were invariably refused. It was dismantled only in 1990.