How French writer Alexandre Dumas discovered Russian cuisine

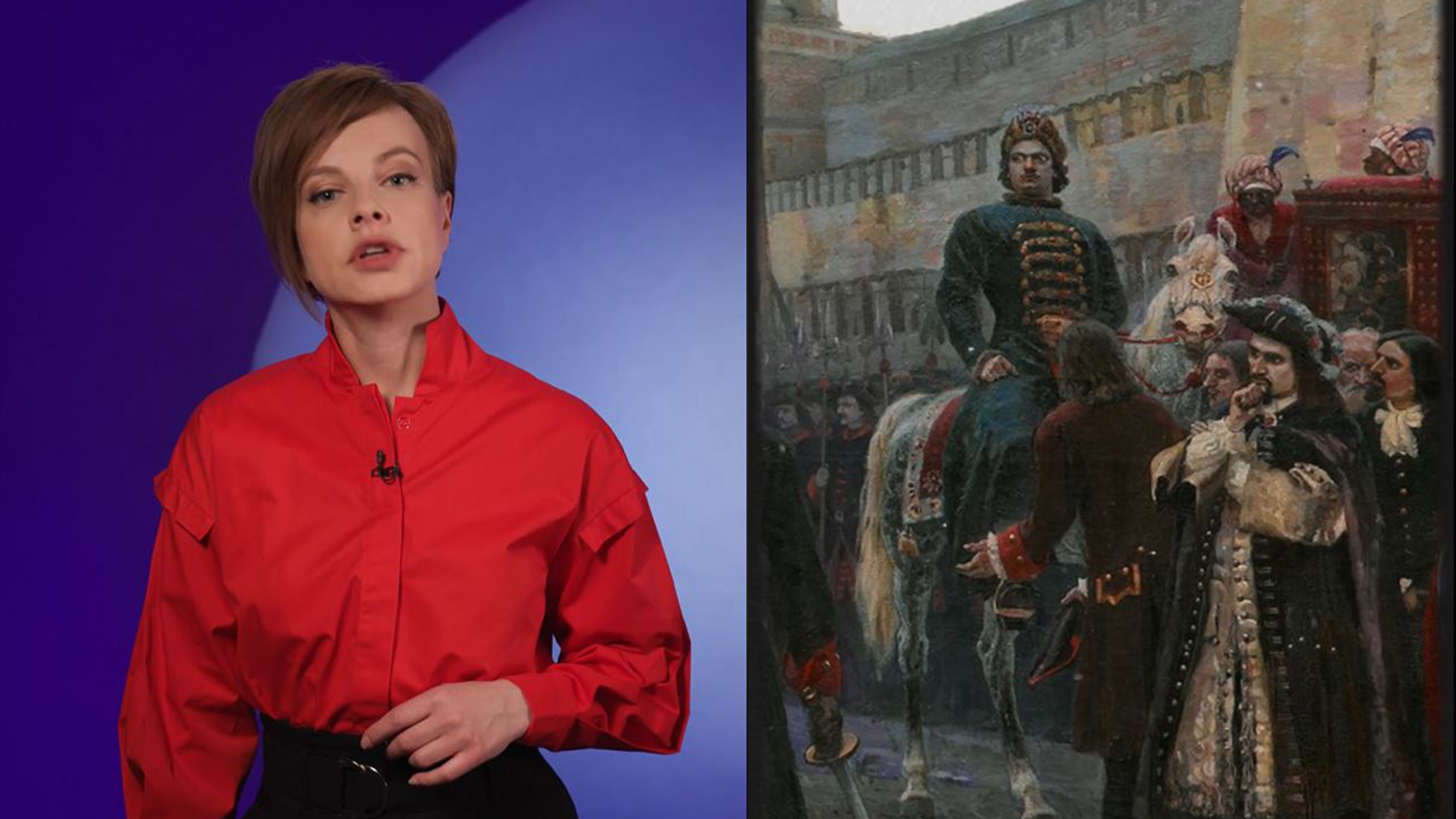

A Frenchman barred from entry

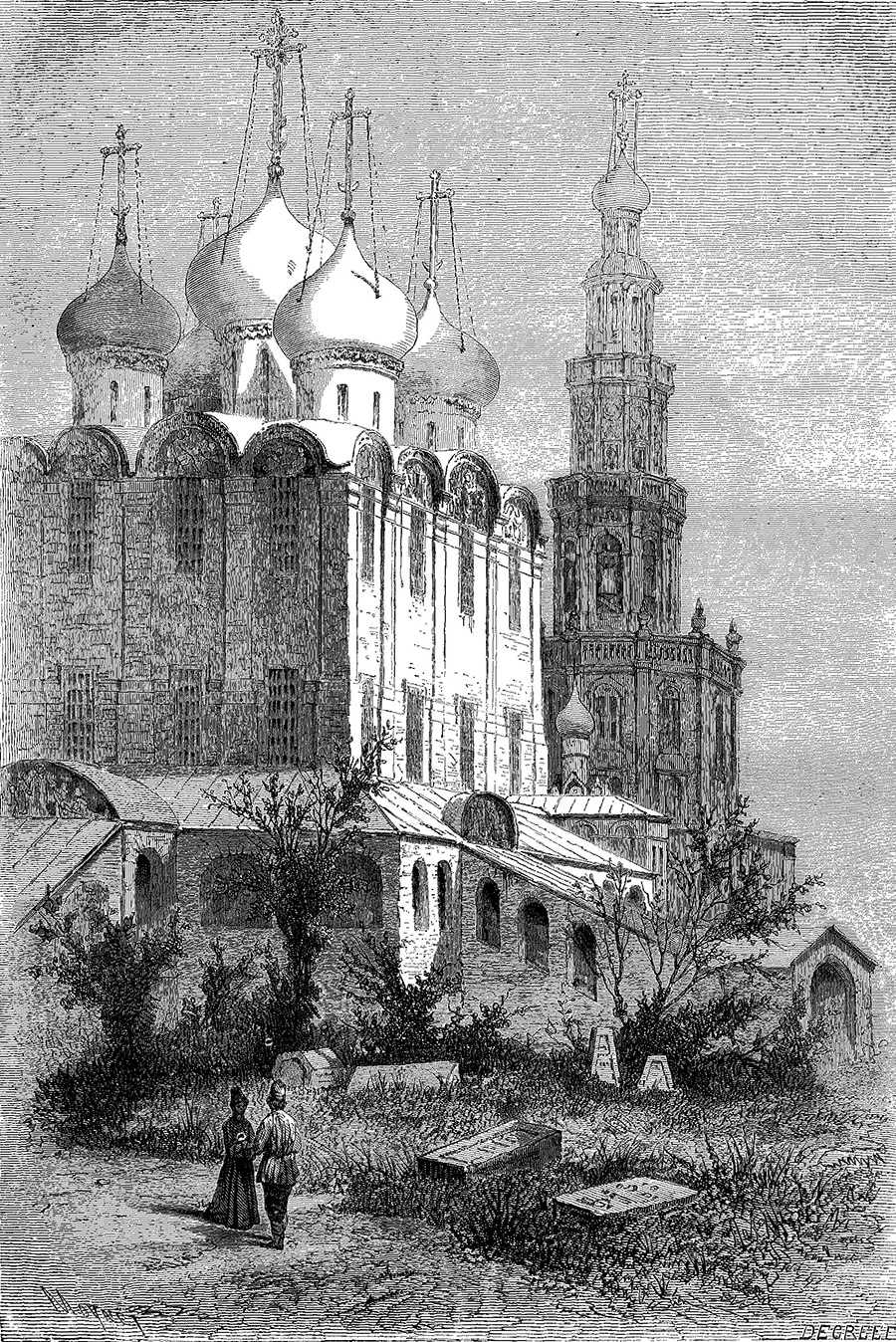

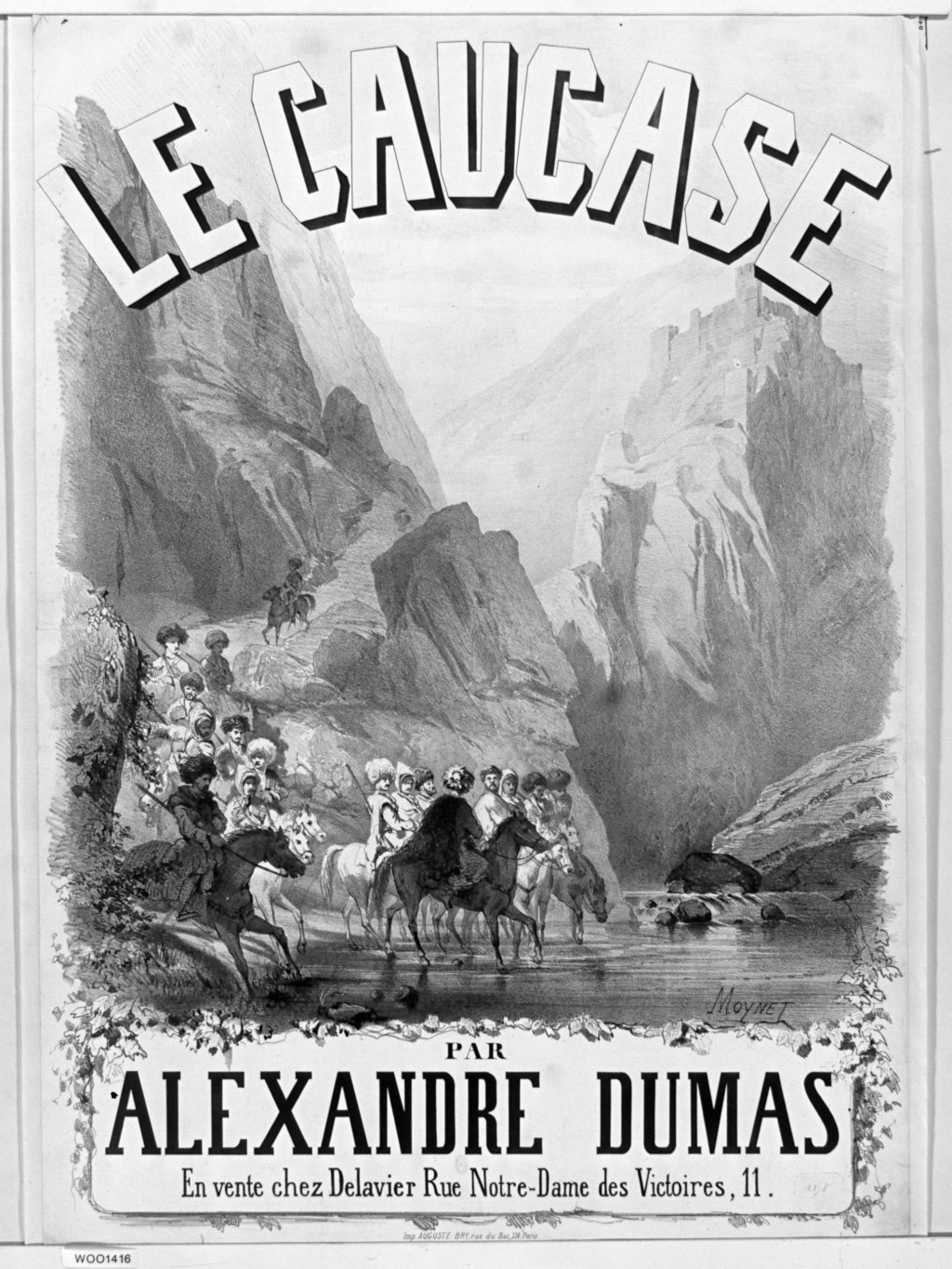

Dumas dreamed of visiting Russia, but nothing ever came of it. After the publication of his novel ‘The Fencing Master’, about the Russian Decembrists and the 1825 uprising, in which the writer directly implicated Alexander I in the conspiracy and assassination of Paul I, any visit to Russia was out of the question. The book was banned and Dumas himself was considered an unwelcome guest. Everything changed only after the accession of Alexander II. Count Grigory Kushelev-Bezborodko unexpectedly invited the writer to his relative's wedding in St. Petersburg and promised to introduce him to Russia. In Summer 1858, Dumas arrived in the northern capital, accompanied by artist Jean-Pierre Moinet.

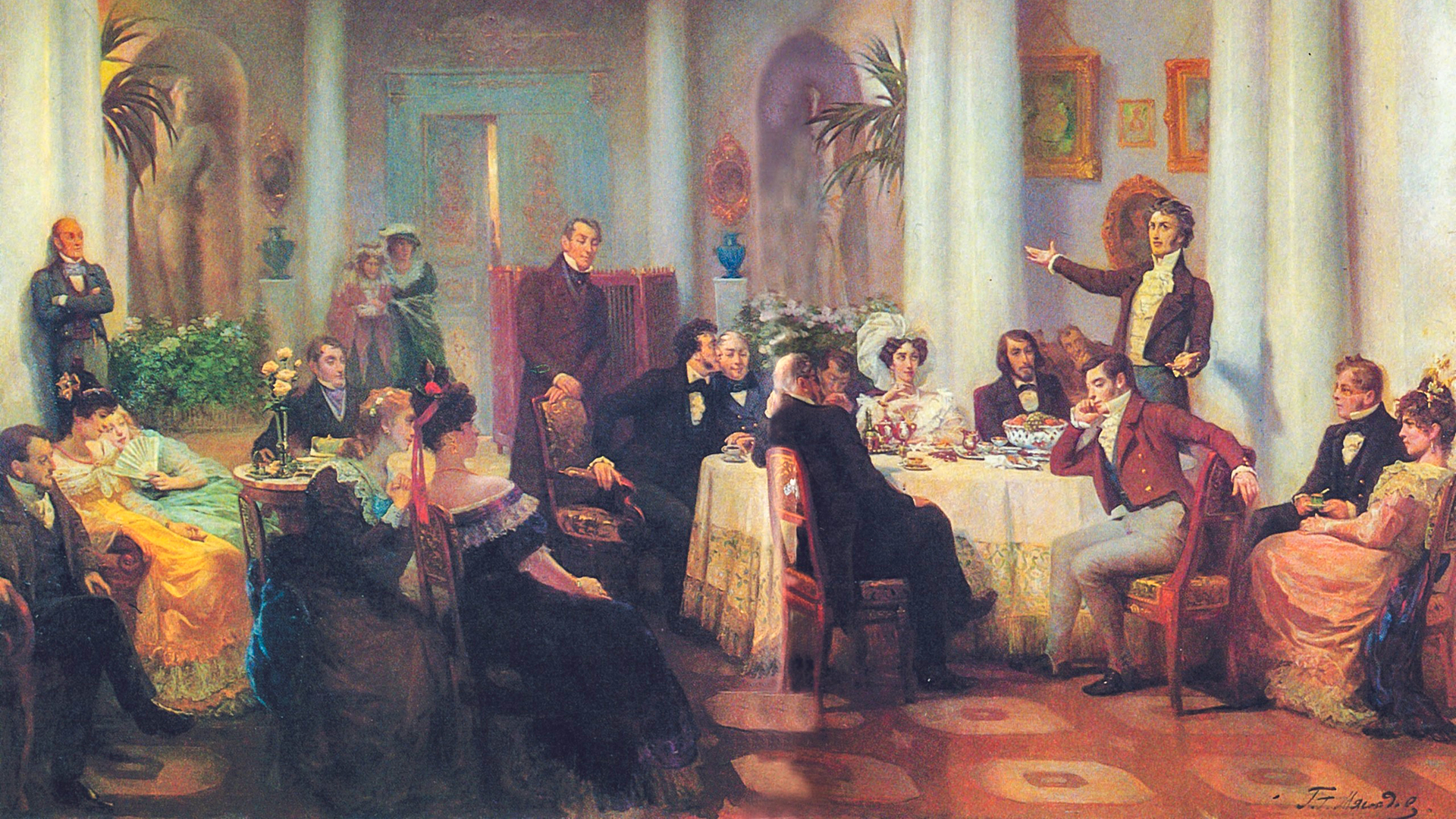

From Table to Table

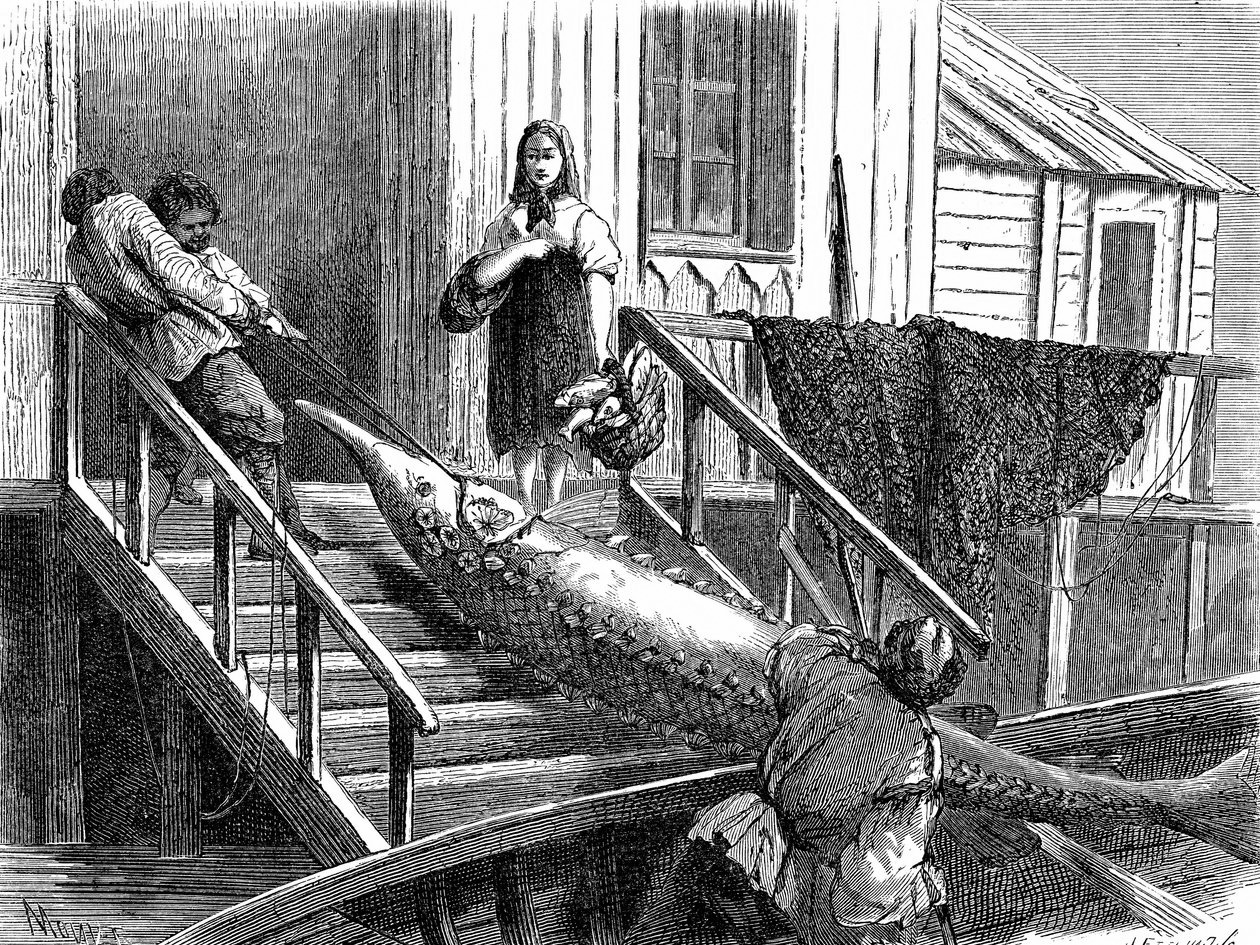

He visited St. Petersburg and Moscow, traveled along the Volga and explored the Caucasus. And, everywhere he went, he would sample the local cuisine. He wrote to his son that he went to Pereslavl to try the famous local herring (a native inhabitant of Lake Pleshcheyevo – vendace, aka a freshwater whitefish – Ed.) and try raw horse meat from the Kalmyks: "A most excellent breakfast – horse thigh!"

He was absolutely delighted with ‘botvinya’, a cold fish soup. "The Russian ‘botvinya’ dish is one of the most delicious in the world. After tasting it, I literally lost my mind." And he also loved lamb shashlik: "In all my travels, I have never eaten anything more delicious," the writer confessed. In his book ‘The Caucasus’, he gave a detailed recipe for it with his comments and recommended marinating the meat overnight for a spicier flavor.

The writer also enjoyed cold boiled stellate sturgeon with horseradish so much that he decided that, if he ever had his own chef, he would allow him to prepare only this dish out of all the vast Russian cuisine.

Strange Russian Soups

However, Dumas still considered French cuisine to be the pinnacle of culinary excellence and was not shy about criticizing the dishes of other countries. And the Russians got their share of it. "You think you're eating meat, but it turns out to be fish. You think you're eating fish, but it turns out to be porridge or cream," he complained.

Many dishes simply struck him as odd. For example, after trying sturgeon fish soup, Dumas delivered a disappointing verdict: "Even if they don't let me into Russia a second time, I must say that sturgeon fish soup is incredibly disgusting." He also disliked ‘okroshka’: "This strange soup is made with onions and green wheat, which is soaked in brine, along with a large quantity of finely chopped shallots and pieces of unripe, cold-killed cucumbers."

Dumas teased Count Naryshkin, who hosted him, saying he preferred the cuisine of Ivan the Terrible ("or Ivan's terrible cuisine").

The Glutton from Paris

The writer not only discovered new dishes, but also diligently wrote down recipes and, whenever possible, took charge of the kitchen. He also devoured food in such quantities that those who received him literally would clutch their heads. In St. Petersburg, Dumas met with writer Avdotya Panaeva. She recalled his visits being "a nightmare": “The Frenchman devoured every last bit of food. He was especially intrigued by the ‘kurnik’, a rich pie with chicken and eggs.”

And it seemed the writer was never full. Panaeva recalled how she once prepared a mountainous feast for him: cabbage soup, rich pies, roast suckling pig, a variety of pickles and appetizers and a sweet pie. Dumas ate it all and, three days later, as if nothing had happened, reappeared. "…Dumas' stomach could have digested fly agarics," Panaeva remarked gloomily.

The writer & cook

Dumas returned to France in Spring 1859. He brought back numerous travel notes from his voyage and, in total, wrote 19 books about his stay in Russia. A "Russian trace" can also be found in one of the writer's most famous novels, ‘The Count of Monte Cristo’, in which sterlet is served.

On the pages of his three-volume essay ‘The Caucasus’, in addition to the shashlik he admired so much, he mentions ‘pilaf’ with chicken, the locals' ability to drink enormous quantities of wine with meals and, finally, crow broth. "Worth two pounds of beef," the writer philosophically noted.

Dumas included Russian recipes in his work ‘The Great Culinary Dictionary’: Its pages mention Crimean wines, as well as jams made from rose petals, pumpkin, nuts and asparagus.