What Russian classic writers thought about FISHING

Theorists & Practitioners

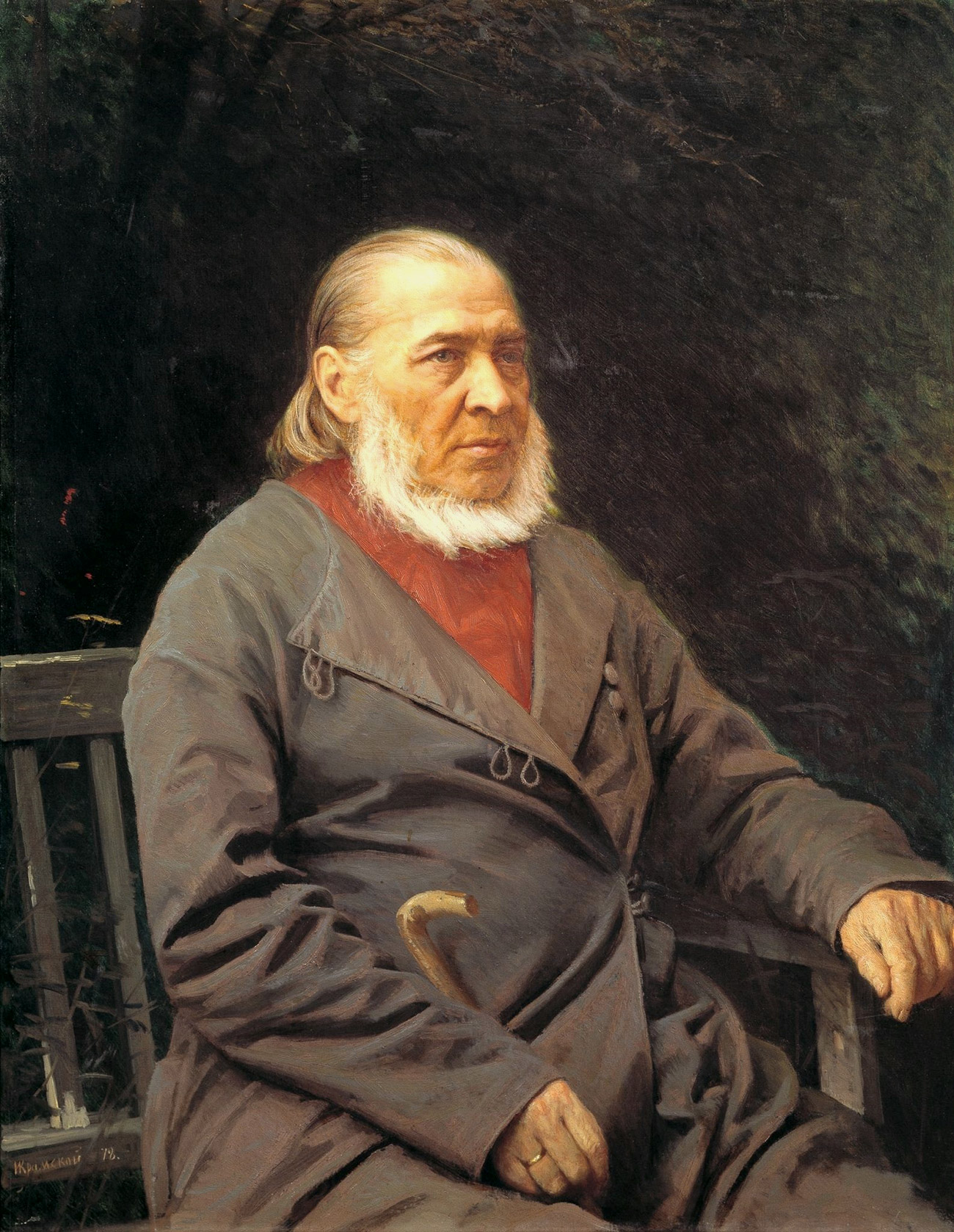

One of the first to express his passion for fishing in literary form was writer Sergei Aksakov, author of the fairy tale ‘The Scarlet Flower’. He himself learned to fish as a child on the family estate. “The fishing rod fascinated me most of all and, under the supervision of my uncle Efrem Yevseich, I devoted myself to fishing with self-forgetfulness…”

Since then, he has not changed his passion. “I first became acquainted with the biggest pleasure of a fisherman, with catching large fish: until then, I had only caught roach, perch and gudgeon… Having put a piece of crushed black bread the size of a large Russian nut on the hook, he threw my rod to the bottom right under the bush and let it go near the shore near the grass and reeds. I sat quietly and did not dare to flinch from my float, which was quietly rowing back and forth…”

In 1847, Aksakov published ‘Notes on Fishing’ with practical advice on where, how and with what to go fishing with. And he was puzzled why many people treated fishing with disdain, calling it “hunting for idle people and lazy people”, “the entertainment of old people and children” and even “the occupation of the feeble-minded”.

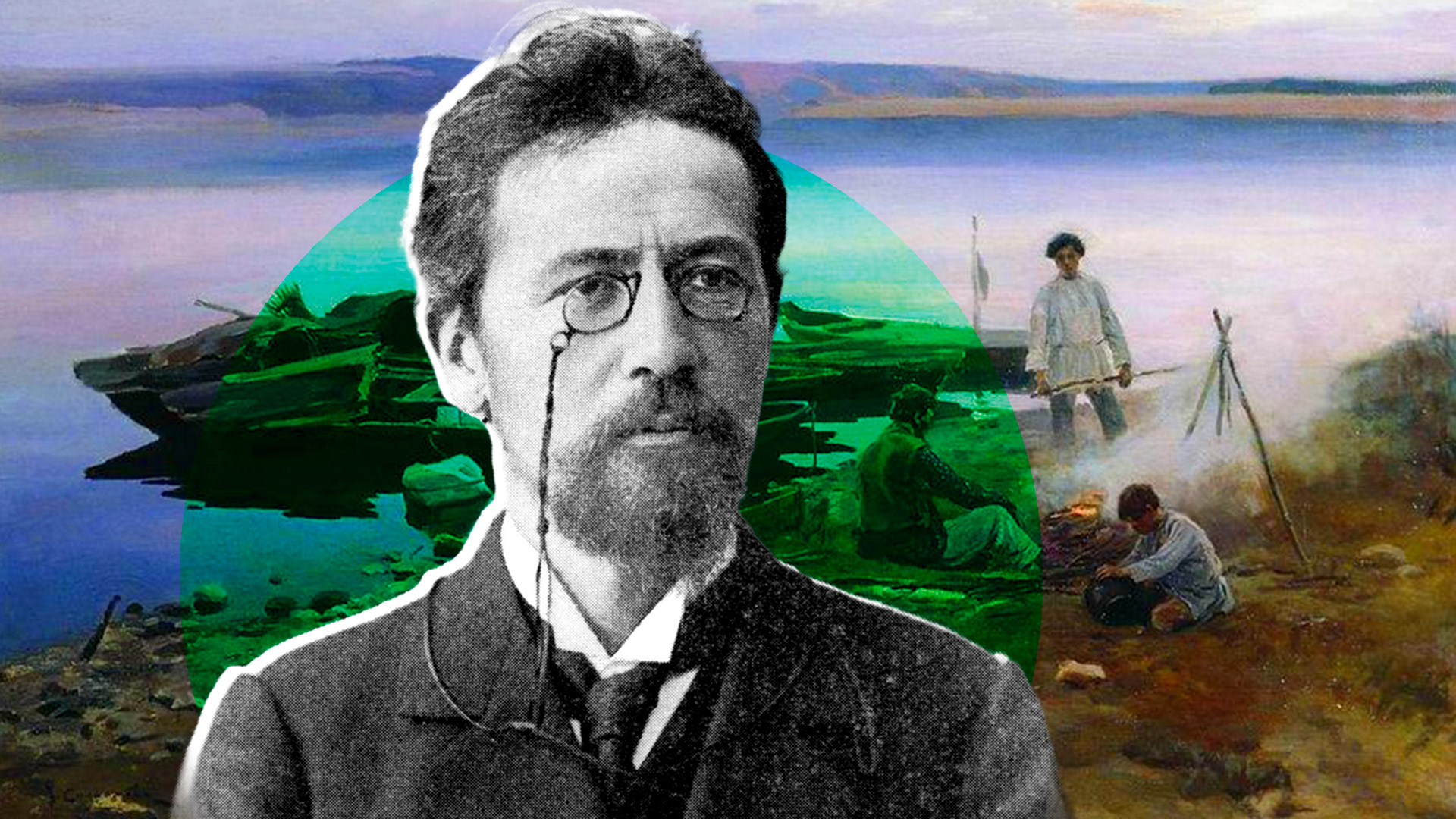

In one of his essays, writer Konstantin Paustovsky admitted: “…deep down in my soul, I never part with the cherished thought of writing a guide to fishing. It should be a kind of encyclopedia of fishing, a story filled with the purest poetry of fishing and everything connected with it.”

In letters to his wife, he wrote: “Dudin arrived at two o’clock in the morning and we drank tea with him at night and discussed all sorts of fishing plans. We spent the first day on the Canal and the second on the Prorva. We caught a pike weighing 14 pounds.”

Passionate Fishermen

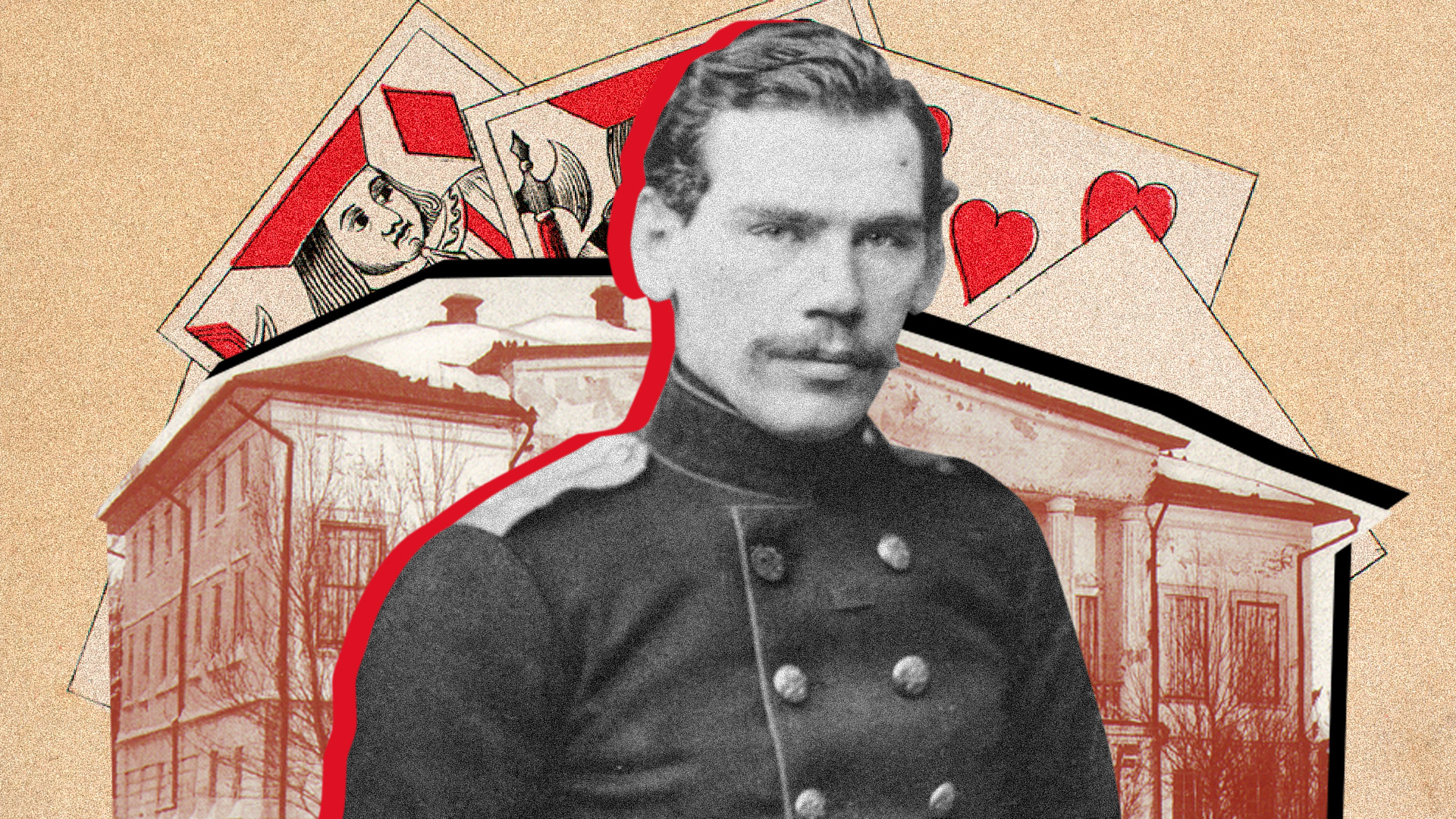

Some writers treated fishing as a sacred act, for the sake of which one could forget about everything. "Writing a feuilleton at a time when you can fish and hang out is terribly hard… And the fishing is superb. The river is in front of my windows – 20 steps away… Catch as much as you can, with fishing rods, weirs and tip-ups…" Anton Chekhov complained in a letter to publisher Nikolai Leikin.

And he confessed the following to publisher Alexander Suvorin: "I love staging a play as much as I love catching fish and crayfish: you throw in a line and wait to see what comes of it? And you go to the Society to receive your fee with the same feeling with which you go to look into a weir or a trap: how many perches and crayfish were caught during the night? It's a pleasant pastime."

At his dacha in Melikhovo, Chekhov even dug a pond where he released fish. According to his brother Mikhail, all kinds of species that live in Russia, except for pike, lived there.

Playwright Alexander Ostrovsky was also a big fan of fishing. The author of ‘The Dowry’ and ‘The Storm’ knew perfectly well when and where it was best to fish and loved sharing advice on tackle and bait. In a letter, he admitted: “…Fishing and the village, in general, always improve me significantly. <…> We don’t have trout or grayling, but spring fishing for live bait is interesting, because of the abundance of the catch. Large predatory fish: pikes, large perches, chubs and asps are constantly being caught.”

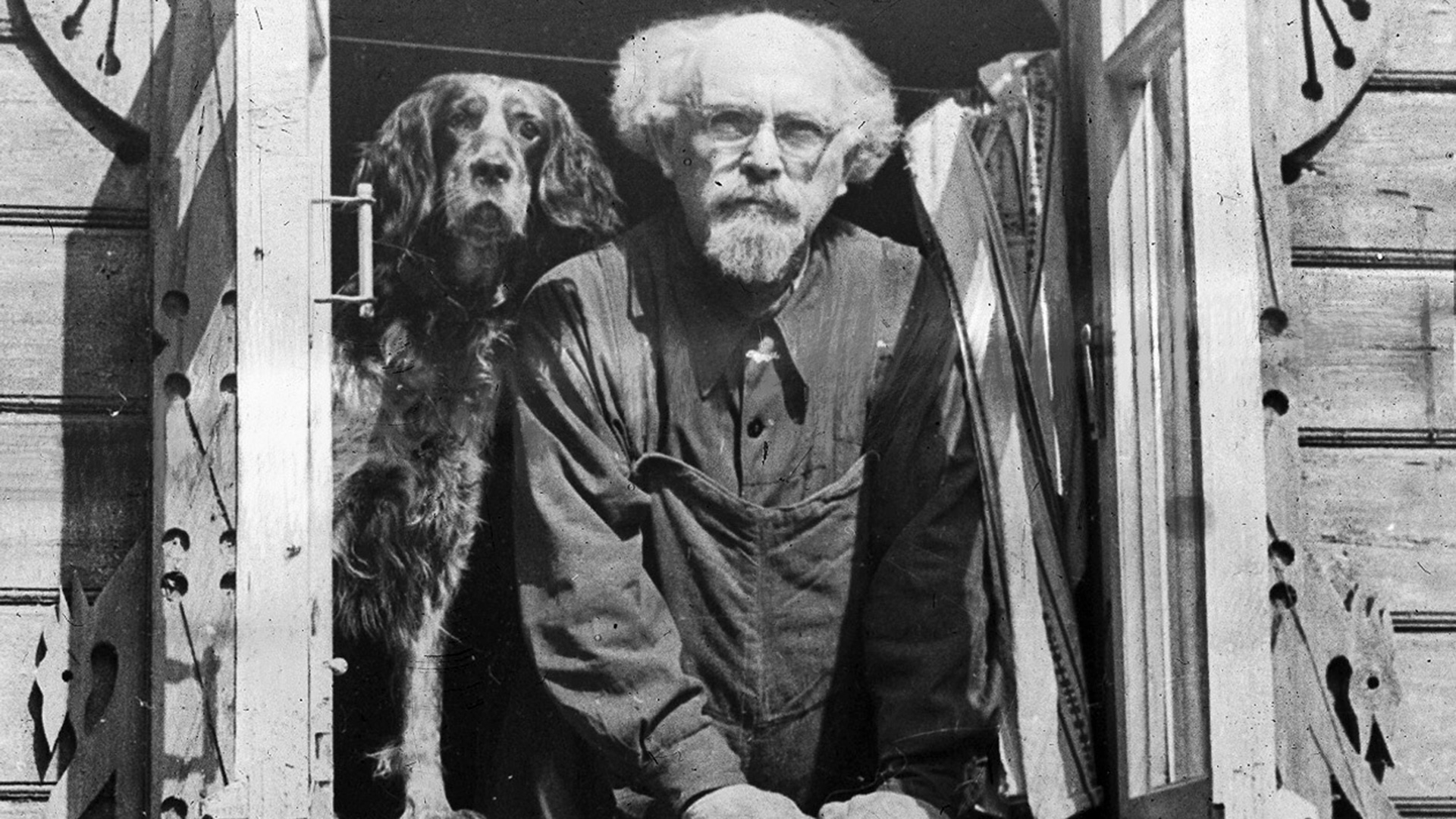

Writer Mikhail Prishvin saw something poetic in fishing. “It’s not the fish that I need, but the thought and feeling that accompany fishing, which is why amateur fishermen sit for days without even knowing it. I’ve realized this so well that I can sit for hours without casting a line. But, sometimes, I feel a kind of guilt about it and then I grab the line. And when you catch a fish, you can think again. So, in the end, to think about the fish, you have to catch it!”