How a Soviet pensioner forged historical artifacts

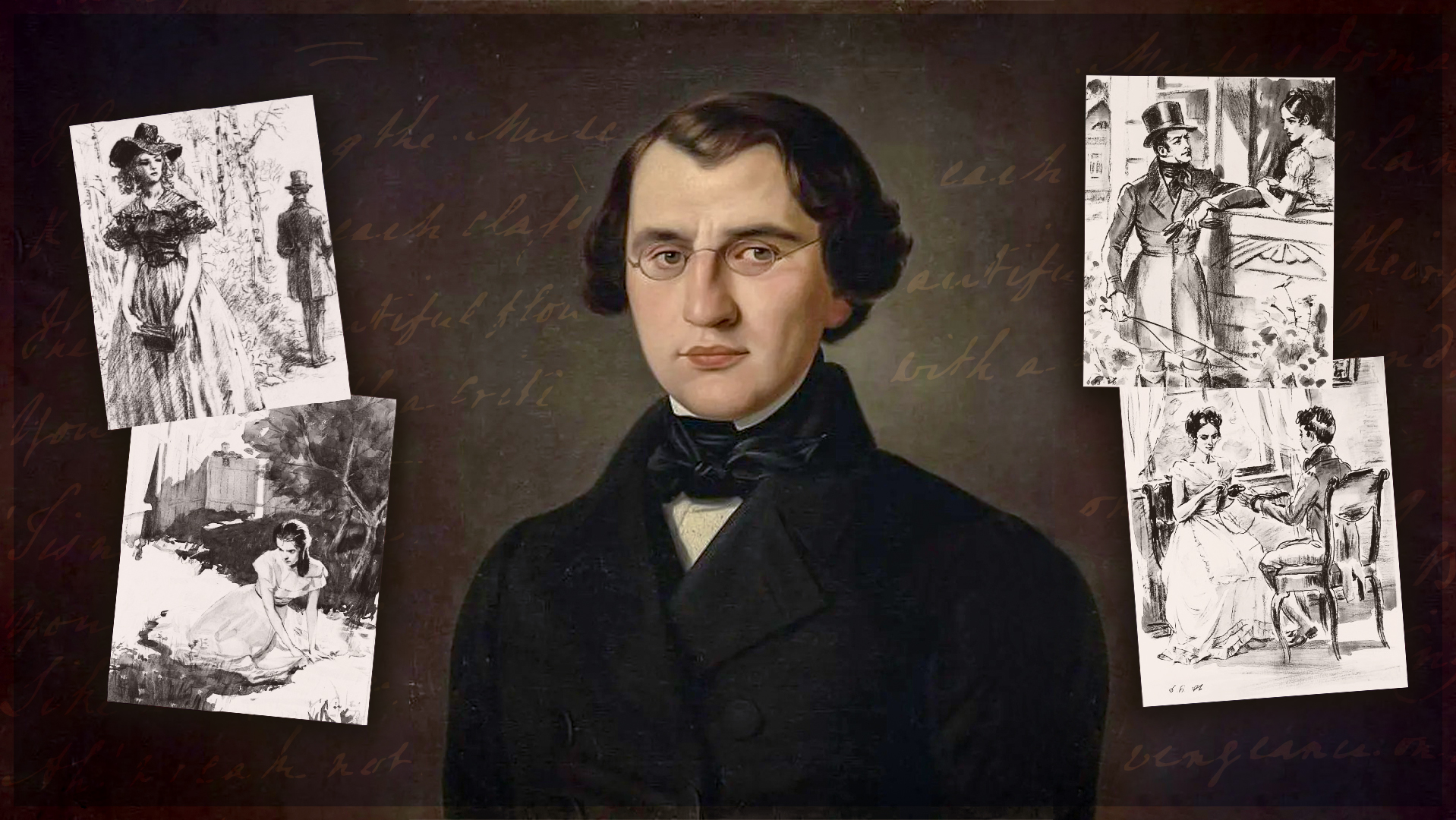

In Soviet times, the figure of poet Alexander Pushkin was literally elevated to a cult. Writer Sergei Dovlatov worked as a tour guide at Pushkin's Mikhailovskoe estate in the 1970s and, in his book ‘Pushkin Hills’, he ironically pokes fun at how the museum staff were fussing over every single of the poet's personal belongings.

Any find associated with Pushkin's name, any of his slightest autograph, an ex-libris or even a material artifact, was perceived as a valuable relic.

Quite often, manuscripts were mistakenly attributed to the poet, but there were cases of deliberate forgeries. The loudest of them is connected with the literary hoax of Antonin Ramensky.

Single pensioner on state benefits

Antonin Ramensky in 1956 (Photo from the book "The dynasty of Ramensky teachers" by M.Makoveev)

Antonin Ramensky in 1956 (Photo from the book "The dynasty of Ramensky teachers" by M.Makoveev)

Antonin Ramensky turned out to be such a skilled mythmaker that, today, it is difficult to determine what facts of his biography are real. He was born in 1913 in Tver Province, graduated from a pedagogical college and taught at a factory school. When he was about 20 years old, he moved to Moscow and became a propagandist and agitator, an activist in the Komsomol (Bolshevik Party youth organization) and then a member of the Bolshevik Party. Party activity was the only way for a man from the provinces without any talents to have a brilliant career.

In the 1950s, Ramensky had some health problems, either because he was beaten during campaigning or because of residual pain from a concussion sustained during the war (although he did not participate in combat). He received a state pension and, sitting at home, began to compose a new biography of his own. In it, he became a lonely pensioner who hailed from an ancient dynasty of teachers.

Fake dynasty

Ramensky family in 1910

Ramensky family in 1910

There actually were some teachers among Ramensky's ancestors: For example, his grandfather taught at a parish school, while his great-uncle was the director of educational institutions in different provinces. And, according to family legend, he was familiar with Lenin's family.

Ramensky (keeping silent about the fact that his ancestors were from the clergy) began to compile a fake pedigree. At first, he was modest in his fantasy and made up only 200 years of family tree, connecting it to Peter the Great. But, later, he expanded the chronology and geography and connected his relatives already to Ivan the Terrible. In this version, all his ancestors were prominent teachers, engaged in educational activities and were familiar with the most famous people of their time – from Pushkin to Lenin.

Ramensky spread his stories with the help of journalists. He kept inventing more and more sensational details about his ancestors. He also invented a fake archive, which allegedly contained thousands of letters from prominent people and material valuables. He even skillfully aged paper for all his hoaxes.

One of his first successful forgeries, which was discussed in the whole of the Soviet Union, were Lenin's "notes" on the text of the first party program. Ramensky also “found” them in his archive.

Forgery of Pushkin's relics

'Ivanhoe' with fake lines and drawings by Pushkin. Infrared photography (from the publication "The Riddle of the Old Book" by N.Deligenskaya)

'Ivanhoe' with fake lines and drawings by Pushkin. Infrared photography (from the publication "The Riddle of the Old Book" by N.Deligenskaya)

The most high-profile cases were associated with Pushkin. Ramensky created a whole fund with Pushkin's relics, forged inscriptions and drawings, sold them or donated them to large institutions. He managed to mislead a huge number of researchers.

In 1963, the Pushkin House in St. Petersburg purchased a volume of Walter Scott's ‘Ivanhoe’ from Ramensky, with notes allegedly made by Pushkin's hand, including a donation inscription and drawings.

"The purchase was sanctioned by several reputable experts and, for almost 30 years, the book was kept among Pushkin's original autographs," says Vladimir Turchanenko, one of the curators of the Pushkin Manuscript Fund.

Ramensky also “found” household utensils and even the poet's baptismal shirt among Pushkin's relics.

Ramensky hoaxes debunked

"Pushkin's turtleneck" and "Arina Rodionovna's towel" in the house-museum of Pushkin's uncle in Moscow

"Pushkin's turtleneck" and "Arina Rodionovna's towel" in the house-museum of Pushkin's uncle in Moscow

The scientific community only suspected forgery 20 years later. In 1985, the reputable ‘Novy Mir’ magazine published a large piece of material, called ‘The Act’, which was a compilation from that very fictional archive. It described in detail the full history of the dynasty and cited letters from famous people addressed to Ramensky.

The family history had already been overgrown with such unimaginable fantasies that this information gathered in one place caused the indignation of historians. They realized that a lot of things just didn't correspond to reality. But, Ramensky was no longer able to respond to criticism – he died later that year.

Ten years later, in 1995, Tatiana Krasnoborodko, a curator of the Pushkin House's manuscript department, examined Pushkin's signature on the ‘Ivanhoe’ volume and, thus, exposed the forgery. And then, she found out that other “finds" were falsifications, as well.

Itomlya coat of arms

Itomlya coat of arms

And yet, according to some experts, Pushkin's fakes made by Ramensky are still kept even in official museums. And the coat of arms of the rural settlement of Itomlya in Tver Region (where Ramensky "found" his archive) still depicts a candle – a symbol of enlightenment, invented by Ramensky.