What’s going on in the painting ‘Assembly under Peter I’ by Stanislav Khelbovsky?

In 1718, Emperor Peter I issued a decree on holding assemblies, which is a French word meaning "a certain number of people gathered together either for their own amusement or for discussion and friendly conversation". They were to be held three times a week, from 5 pm to 10 pm. The locations were appointed by the chief of police in St. Petersburg and the commandant in Moscow. And the dress code was strictly European.

Women's issue

The presence of women was mandatory – a decision that was almost scandalous for that time. After all, before Peter I, girls and women spent almost all their time at home, with the possible exception of going to church. And, for entertainment, they had stories and jokes from nannies, jesters, servants and old women-pilgrims.

However, Peter was adamant: during dances at assemblies, young people had to get acquainted and, in the future, get married. The courtiers did not know how and did not like to gracefully twirl in polonaises, contradanses and minuets to foreign music. But, the emperor taught them by personal example. And those who stumbled and fell were punished: he made them drink a large cup of wine!

At first, after dancing, men and women went to different sides of the room and did not engage in any conversations. Some courtiers even complained that, because of this, "everyone sits like dumb and just looks at each other” at the assemblies."

After the dances, dinner or cold appetizers were served, and at 10 pm, after an announcement about where the next assembly would take place, the reception ended. Over time, people got used to the assemblies, as well as to European dances and outfits and, gradually, they transformed into balls.

No more caftans

Anyone could attend the assemblies, with the exception of servants and peasants. Moreover, the host was not obliged to greet the guests, even if the emperor himself came to his house. This rule was supposed to give the assemblies an informal character. Usually, guests danced in one room, played chess or checkers in another and had conversations over a pipe in a third. If the house was small, then everything took place in one space.

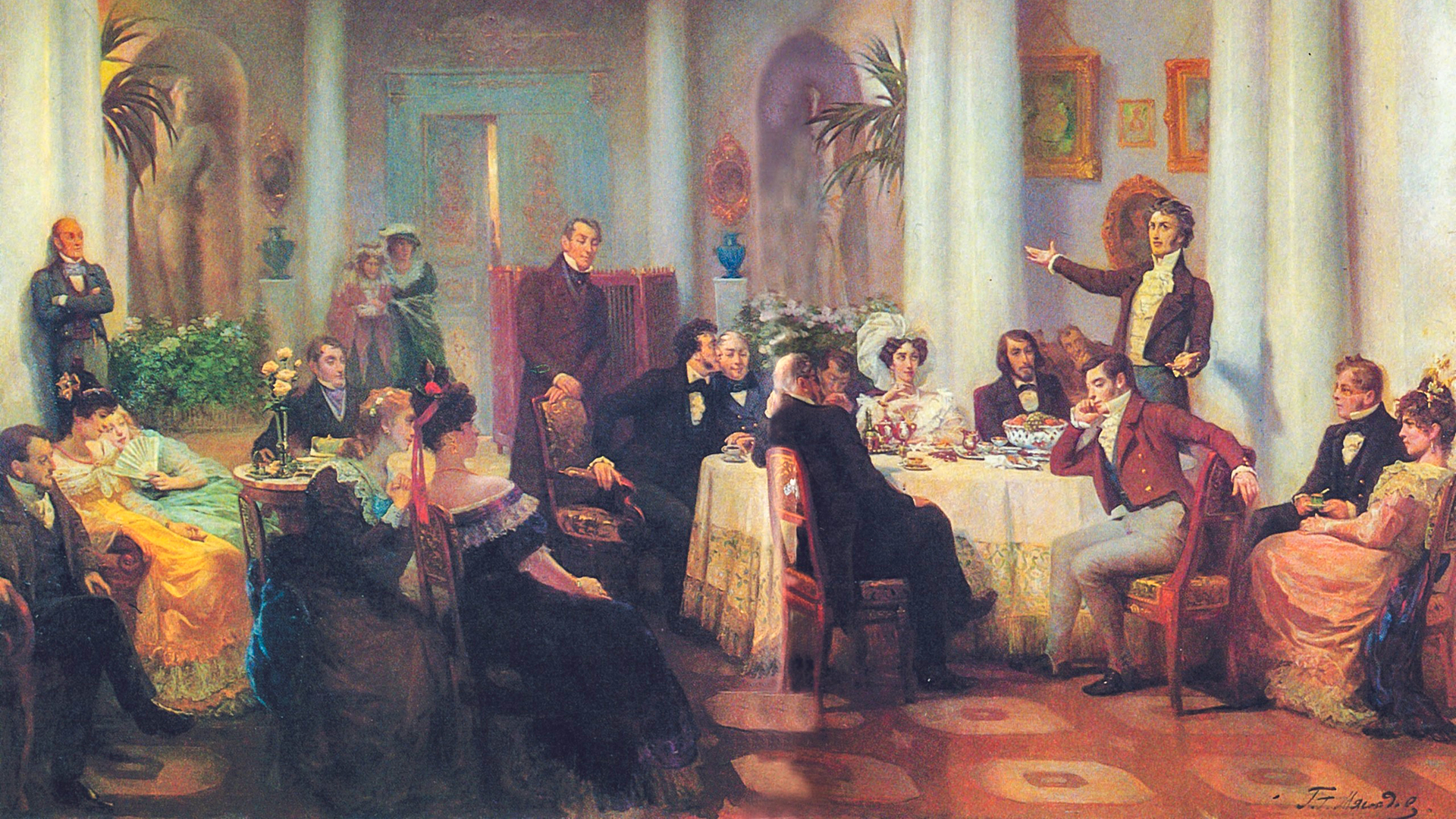

Khlebovsky's painting depicts not just one of the assemblies, but literally a style guide for such a reception. The guests are dressed in the latest fashion, with wigs on the heads of both men and women. Servants are carrying snacks. The emperor is sitting at the table – apparently, he has just been distracted from a chess game with a courtier. Through the slightly open curtain, it is visible that there are also guests in the next room – it seems that dancing is in full swing there.

The attention of those gathered is riveted to a stately gray-bearded man in an expensive caftan, who, with a gesture, refuses a cup offered to him. Several violations are evident at once: by that time, Peter had ordered the courtiers to get rid of their beards and switch to European clothing. One guest, it seems, decided to disregard the royal decrees and, on top of everything else, refused the "penalty cup" that the servant was giving him.

So, it seems most likely that a scandal is brewing: the guests of the evening are not hiding their surprise, looking at the newcomer and whispering. And some are looking at the emperor, waiting for his decision. Catherine I, the wife of Peter I, in a white dress with a blue ribbon, is also watching the scene with interest, standing in the company of one of her daughters.

For this painting, artist Stanislav Khlebovsky received a small gold medal in 1858. In 1940, the canvas was transferred to the Russian Museum, where it remains to this day.