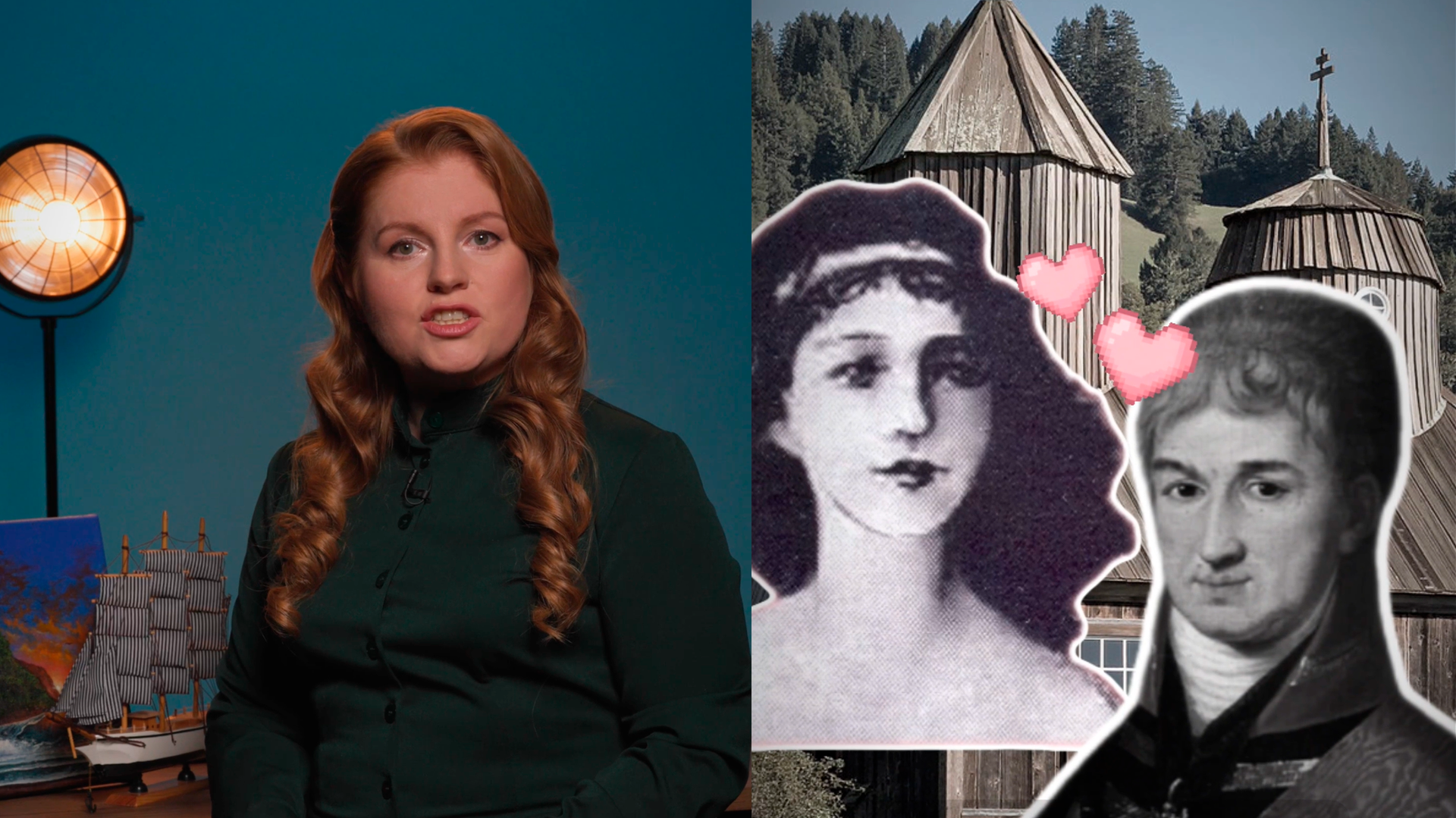

How a Russian poet-nun became a heroine of the French Resistance

Liza was born in Riga (then the Russian Empire), where her father served as an assistant prosecutor, in December 1891. Four years later, the family moved to Anapa, where they inherited two estates with 2,500 hectares of land.

In 1906, her father passed away, so her mother sold part of the family lands and moved with her children to live in St. Petersburg. There, three years later, Liza graduated from high school with a silver medal and entered the history and philology department of the Bestuzhev Courses.

In 1910, she married lawyer and historian Dmitry Karavaev-Kuzmin. But, three years later, she left for Anapa. Life in St. Petersburg oppressed her and her relationship with her husband deteriorated. In October, she gave birth to a daughter, whom she named Gayana – or “earthly”. The identity of Gayana's father remained a secret.

Liza "wanted glory – to die for all the untruths of the world". She "dreamed of meeting real revolutionaries, who were also ready to sacrifice their lives every day for the sake of the people". During these years, she studied theology and even took exams at the St. Petersburg Theological Academy. She did this "for herself" – women could not be theologians at that time.

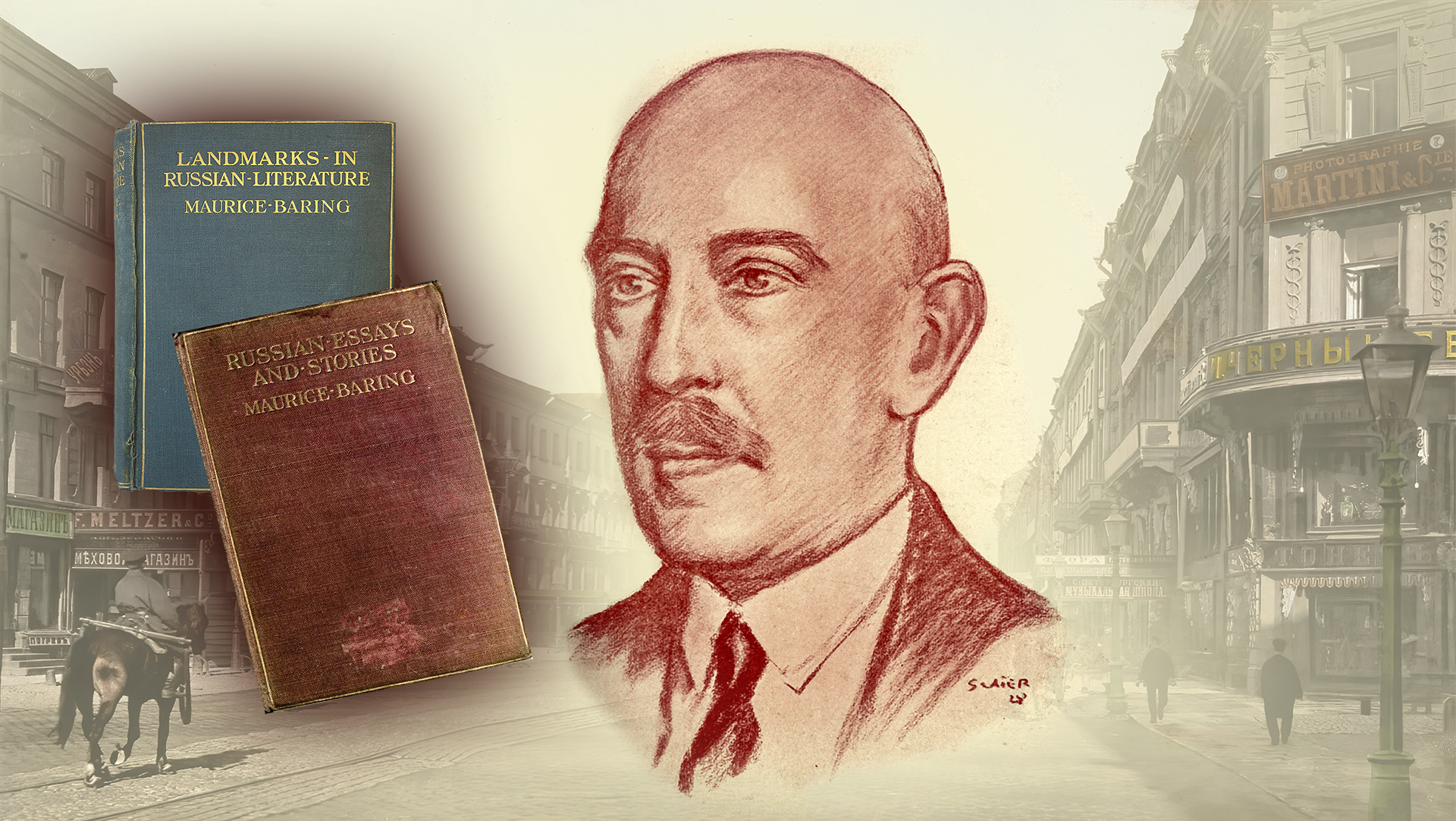

In 1915, she published the religious and philosophical story ‘Yurali’. Its main character is a poet, wanderer, preacher and sage, who attempts the evangelical path of Christ and defines the moral criteria with which one should treat life and people's actions. A year later, her ‘Ruth’ poetry collection was published.

She enthusiastically accepted the February Revolution. She imagined the future of Russia as a happy life of the people creating a new society on a Christian basis. She voluntarily transferred more than 60 hectares of her land and her grandfather's house, where a school was located for many years, to the Cossacks for free use.

In the spring, she joined the Socialist Revolutionary Party. She was elected to the renewed, "democratic" city council, where the Socialist Revolutionaries made up the majority.

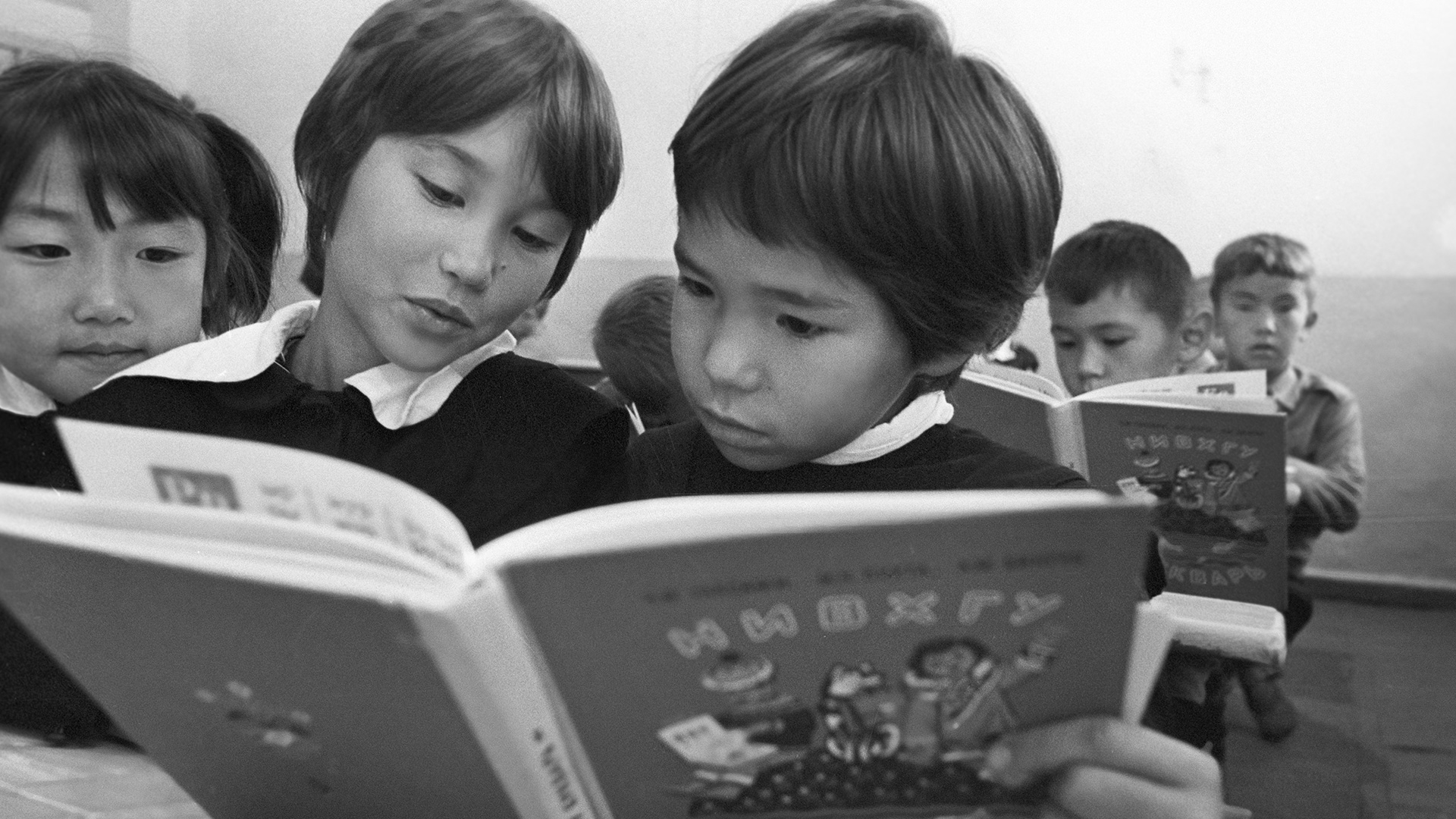

But, on Christmas Day 1918, the Bolsheviks appeared in the city. Pavel Protapov, a professional revolutionary who had contracted consumption in prisons and exile, arrived from Novorossiysk, where Bolshevik committees were already operating. The first meeting under his chairmanship decided to create a military revolutionary committee. The new committee and the paramilitary company under it took over the bank, post office, telegraph, telephone and printing house and nationalized other city institutions and private enterprises. Elizabeth ran for the post of assistant to the city mayor, wanting to control the health and education departments and prevent the looting of property. At the end of February, the acting mayor resigned and she took his place: now she was fully responsible for the management of the city's economy and negotiated with the Bolsheviks, as she put it, face to face.

Karavaeva-Kuzmina and Protapov had much in common: they were almost the same age and both were born in Riga. But, they stood on different sides of the barricades. Elizaveta called Protapov a "romantic dictator". The harshness of his policies did not overshadow his ability to be a knight in his own way. “My proposal was strong enough and I could achieve a lot, mainly because I was a woman,” she recalled. For her courage, she was forgiven for things that the Bolsheviks would not forgive any man.. "If, as a result of some dispute with the Council, I felt that things were heading towards my arrest, I would declare: ‘I will make sure that you arrest me’," to which the hot and romantic Protapov would shout: "Never. This would mean that we are afraid of you."

Two weeks after her election as mayor, the city council resigned. That meant the work of the council was paralyzed. But, Elizaveta did not give up. She helped women from the Union of Frontline Wives and once lined them up ten in a row to go to the treasury, which had been seized by the Bolsheviks, to demand the payment of benefits. She helped refugees, saved teachers whom the Bolsheviks arrested for “counter-revolutionary statements” and saved people from reprisals.

At that time, she met Daniil Skobtsov, a deputy of the Kuban Regional Council. He came from a poor Cossack family and had achieved everything himself. He became the very "earthly man" whom she once wanted to find. In the Summer of 1919, they married. Now, for the poetess, family became the most important thing in her life. From 1917 to 1923, she wrote almost nothing. Even work in the Social Revolutionary Party no longer attracted her. She was convinced that the revolution resulted in the death of Russia, but also that this was the fulfillment of God's will, the atoning sacrifice that the Russian people made for the future of all mankind.

In March 1920, Anapa was taken by the Red Army. Elizabeth fled to Georgia, where her son Yuri was born. They were finally united with Skobtsov in Constantinople (now Istanbul) at the end of the year. And, in December 1922 in the Serbian city of Sremski Karlovci, she gave birth to a daughter – Anastasia. In 1924, the family finally settled in Paris.

The death of little Nastia from meningitis in 1926 was a great blow to Elizabeth and prompted her to decide to become a nun. On March 16, 1932, in the church of the St. Sergius Metochion of the St. Sergius Orthodox Theological Institute in Paris, she took the monastic veil and received the name Maria – in honor of St. Mary of Egypt.

Mother Maria did not shut herself away within the walls of the monastery. She set up hostels and canteens for the needy, found food, clothing, money for those who needed it, visited institutions for the mentally ill and opened a sanatorium for tuberculosis patients, which later became a nursing home.

When the Nazis occupied Paris, Mother Maria hid Jews, escaped Soviet prisoners of war and French underground fighters in her shelter on Lourmel Street and prepared documents for their transfer to safe places. Many arrested Russian emigrants received parcels from her in prison. She spent three days at the Paris Velodrome, where the Nazis rounded up Jews, destined for Auschwitz. From there, she managed to smuggle out four children in trash bins.

On February 8, 1943, the Gestapo conducted a search on Lourmel Street and arrested Yuri, the son of Mother Maria and one of her main assistants. The next day, she herself went to the Gestapo: she was assured that Yuri would then be released. But, the promise was not kept. Mother Maria's final martyr's path began, ending with her death in the Ravensbrück gas chamber on March 31, 1945. Yuri, meanwhile, died in the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp in 1944….

This material is published in an abridged form – the original was published in the ‘Russky Mir’ magazine.