How a native of the Russian Empire saved dozens of Jews from a train headed for Auschwitz

In August 1942, the Nazis began the deportation of Belgian Jews to concentration camps in Eastern Europe, mainly to Auschwitz. They used special convoys, which were heavily guarded by the security police. The trains departed from Mechelen Station, located between Brussels and Antwerp. There was a transit camp there, commonly known as the ‘House of Death’.

Mechelen transit camp

Mechelen transit camp

On April 19, 1943, the 20th convoy was preparing for departure. There were 1,631 people in the carriages, including 262 children. After one of the unsuccessful escape attempts, the Nazis increased security measures. They used tightly closed freight wagons, the windows of which were surrounded by barbed wire.

Belgian deportation wagon

Belgian deportation wagon

It seemed that the prisoners of the 20th convoy didn't have the slightest chance of escaping. They could not have known that, meanwhile, three young men on bicycles were rushing to their aid through the rugged terrain. Armed with pliers, a flashlight and a single pistol, they planned to attack the "death train".

Descendant of Moldovan Jews in the ranks of the Belgian Resistance

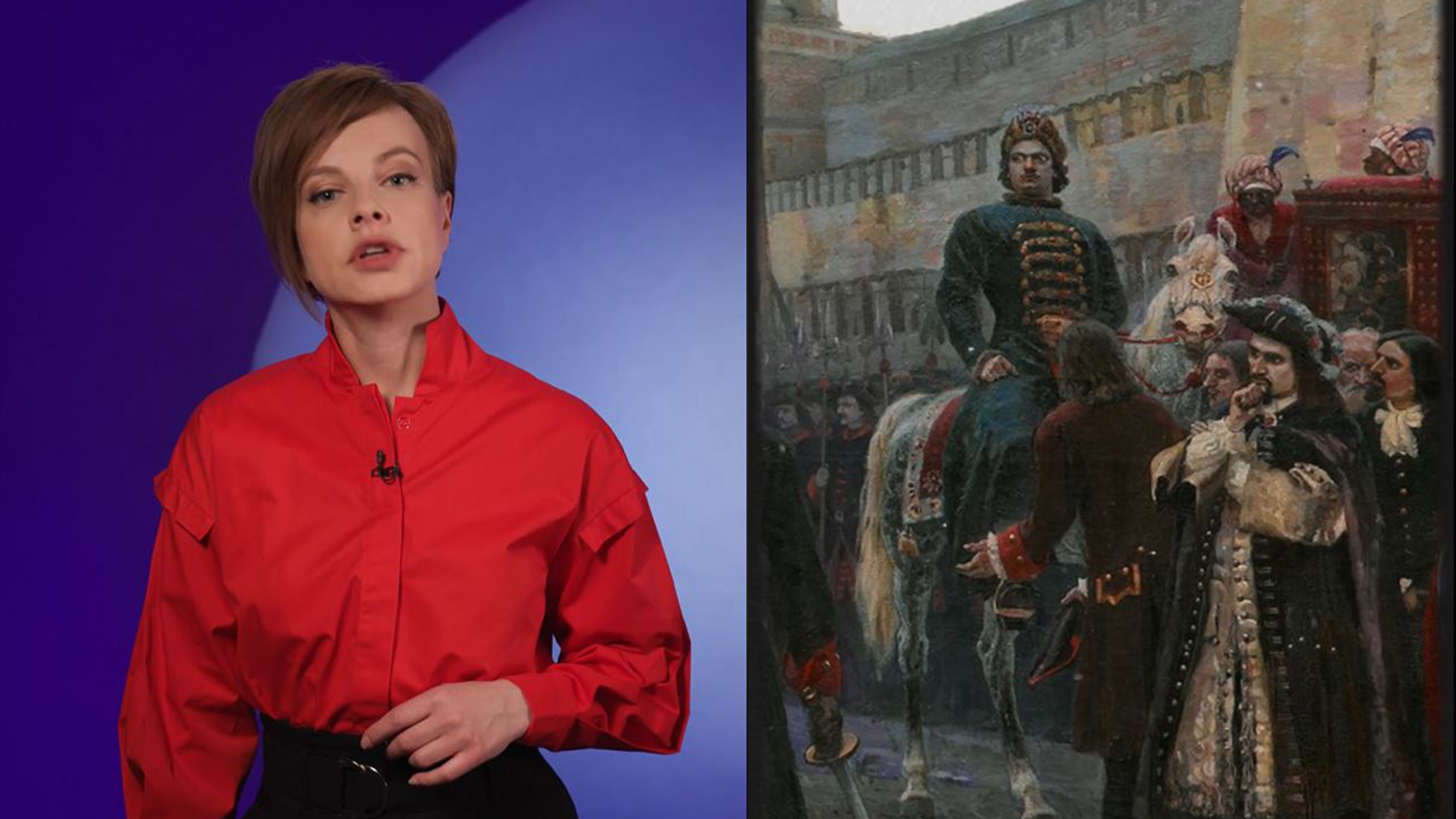

Youra 'Georges' Livchitz

Youra 'Georges' Livchitz

The leader and ideological inspirer of the daredevils was Youra 'Georges' Livchitz. He was born in 1917 to a family of Jews from Bessarabia (a historical area in Moldova), living then in Kiev (then part of the Russian Empire). When Youra was 11 years old, his parents divorced and his mother took the children and moved to Belgium.

Youra wanted to become a military doctor, so he began studying medicine at the Free University of Brussels. In June 1942, a law was passed in Belgium prohibiting Jews from practicing medicine, but the young man managed to get a job at the St. Pierre Hospital in the capital and then, at the ‘Pharmacobel’ pharmaceutical company.

Despite his relative well-being, Youra couldn't calmly take the extermination of the Belgian Jews. So, he joined the Resistance members from the Free Belgian University, who had formed the so-called ‘General Sabotage Group of Belgium’ (‘Group G’).

Three students VS the ‘death train’

The comrades initially rejected Livchitz’s idea to attack the 20th convoy, considering it too risky. Only two friends supported Youra: Jean Franklemon and Robert Maistriau. And, together, they began to implement the plan.

On the day of the attack, after hiding their bicycles, the young men approached the railway tracks, along which the ‘death train’ was already racing, and installed a lantern on them. Then, they covered the lantern with a paper napkin to make it light red and started waiting.

Robert Maistriau's medal, the pistol and the storm lamp

Robert Maistriau's medal, the pistol and the storm lamp

And their plan worked! When the driver saw the red signal light on the tracks, he stopped the train. Youra set off along the train, firing chaotic shots into the air, trying to create the illusion of a massive attack. By this time, his friends were already hurriedly cutting the barbed wire of the first car they came across with pliers.

By the time the guards of the train figured out the trick with the flashlight, the friends managed to free 17 people. But, the train did move on. Nevertheless, Jean and Robert managed to hand over the tools to the other prisoners, so that they could try to free themselves. Risking his own life, the driver slowed down as much as possible to give the prisoners the opportunity to jump off.

Deportation carriage of Mechelen transit camp

Deportation carriage of Mechelen transit camp

More than 233 Jews managed to escape before the 20th convoy reached the Belgian border. 25 of them were shot on the spot, while 92 were recaptured. However, thanks to the feat of those three brave men, 118 Jews managed to avoid deportation.

Sacrificed life for the freedom of others

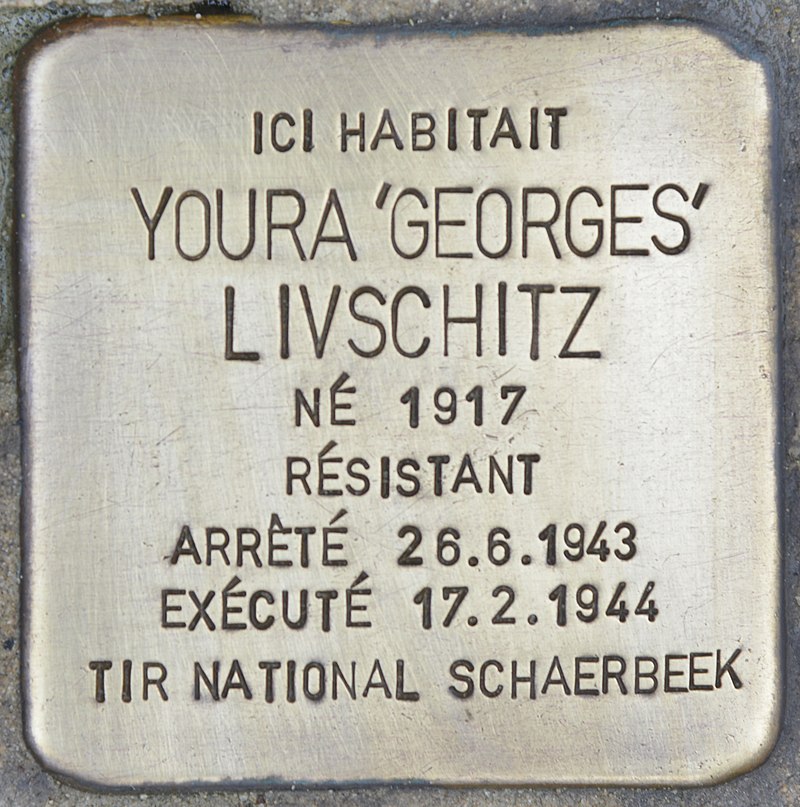

“Stolpersteine”, or “stumbling stone” of Youra Livchitz in Brussels

“Stolpersteine”, or “stumbling stone” of Youra Livchitz in Brussels

Youra Livchitz paid with his own life for the attack on the 20th convoy. At first, he managed to hide at his girlfriend’s parents’ place, but, eventually, the Gestapo tracked down his trace.

Mechelen transit camp

Mechelen transit camp

Youra made an attempt to escape from arrest, planning to take refuge in the UK, but he was captured again and sent to Fort Breendonk, a concentration camp near Antwerp in Belgium. On February 17, 1944, the Nazis executed him along with other fighters of the Belgian Resistance. In his last letter to his mother, he wrote: "Consider that I died at the front line."

As for Jean Franklemon and Robert Maistriau, his Belgian comrades, they also went through the horror of concentration camps, but managed to survive and ended their lives as free men in Belgium.

Memorial to the Attack on the twentieth convoy

Memorial to the Attack on the twentieth convoy

The act of the brave trio was the only attack on the ‘death train’ ever recorded.