5 works by Russian writers about foreign geniuses

British intellectual and Booker Prize winner Julian Barnes studied Russian in his youth. And, in 1965, in the company of his student friends, he took a long road trip around the USSR in a minibus, visiting Minsk, Smolensk, Moscow, Leningrad, Kyiv and Odessa. Since then, his interest in Russian culture has not faded. In 2016, he published a novel about Russian composer Dmitry Shostakovich, ‘The Noise of Time’. Barnes' interest in Shostakovich, one creative person's interest in the fate of another, is not unique. Below, we recall the works of Russian classic writers dedicated to great Europeans.

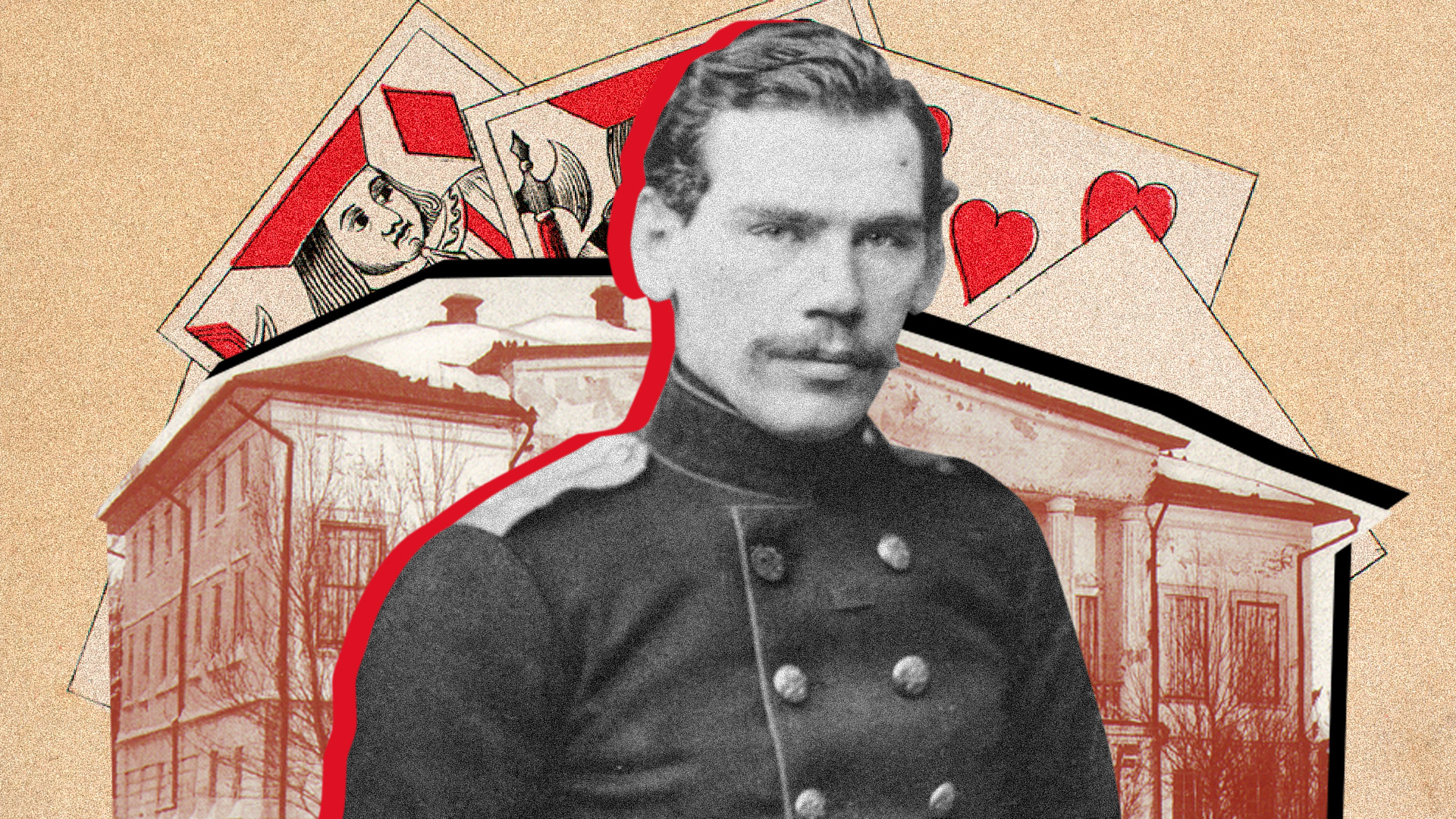

Alexander Pushkin, ‘Mozart and Salieri’

This is a short play written in 1830 about the nature of genius. According to Pushkin, Mozart is a frivolous genius, while Salieri is a hard-working mediocrity. Salieri envies Mozart's talent. He is offended that he writes great music without any effort, while he is forced to work hard on each melody. And, as a result, Salieri decides to poison Mozart. It is known that, in reality, this did not happen, but Pushkin needed this plot twist for "literary plausibility".

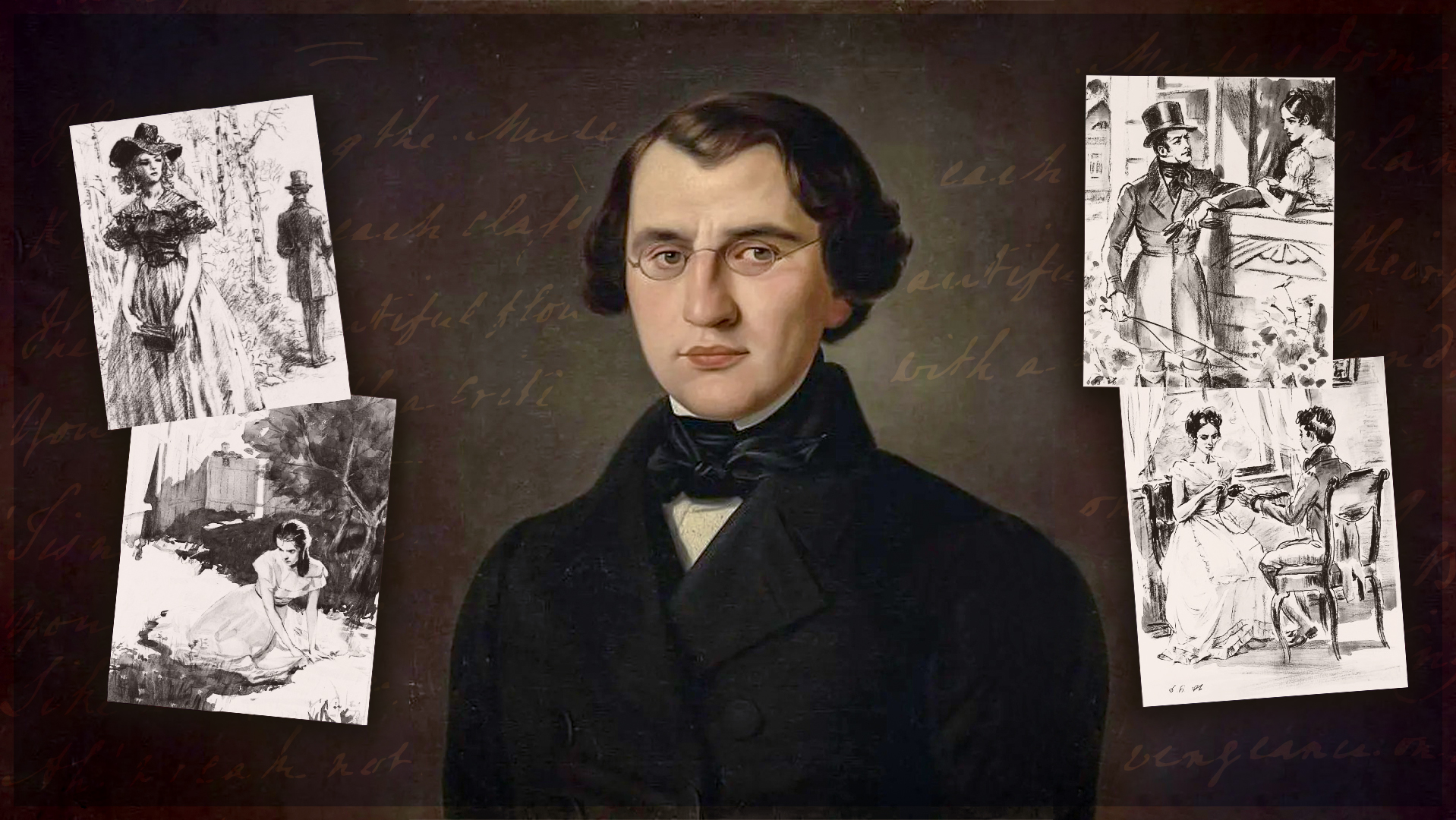

Ivan Turgenev, ‘Hamlet and Don Quixote’

On January 10, 1860, at a public reading for the benefit of needy writers and scientists, Turgenev delivered a speech titled: ‘Hamlet and Don Quixote’. In it, he analyzed in detail two, from his point of view, opposite personality types. First, the distinctive features of the image of Hamlet, according to Turgenev, were as follows: "Analysis, first of all, and egoism and, therefore, unbelief. He lives entirely for himself, he is an egoist." The type of Don Quixote, on the other hand, as understood by the Russian writer, was as follows: "He lives entirely (if one can put it that way) outside himself, for others, for his brothers, for the destruction of evil, for counteracting the forces hostile to humanity – wizards, giants, i.e. oppressors. There is not a trace of egoism in him, he does not care about himself, he is all self-sacrifice – appreciate this word! – he believes, believes strongly and without looking back." Reflections on the characters also become a reason for studying the nature of the talent of Shakespeare and Cervantes.

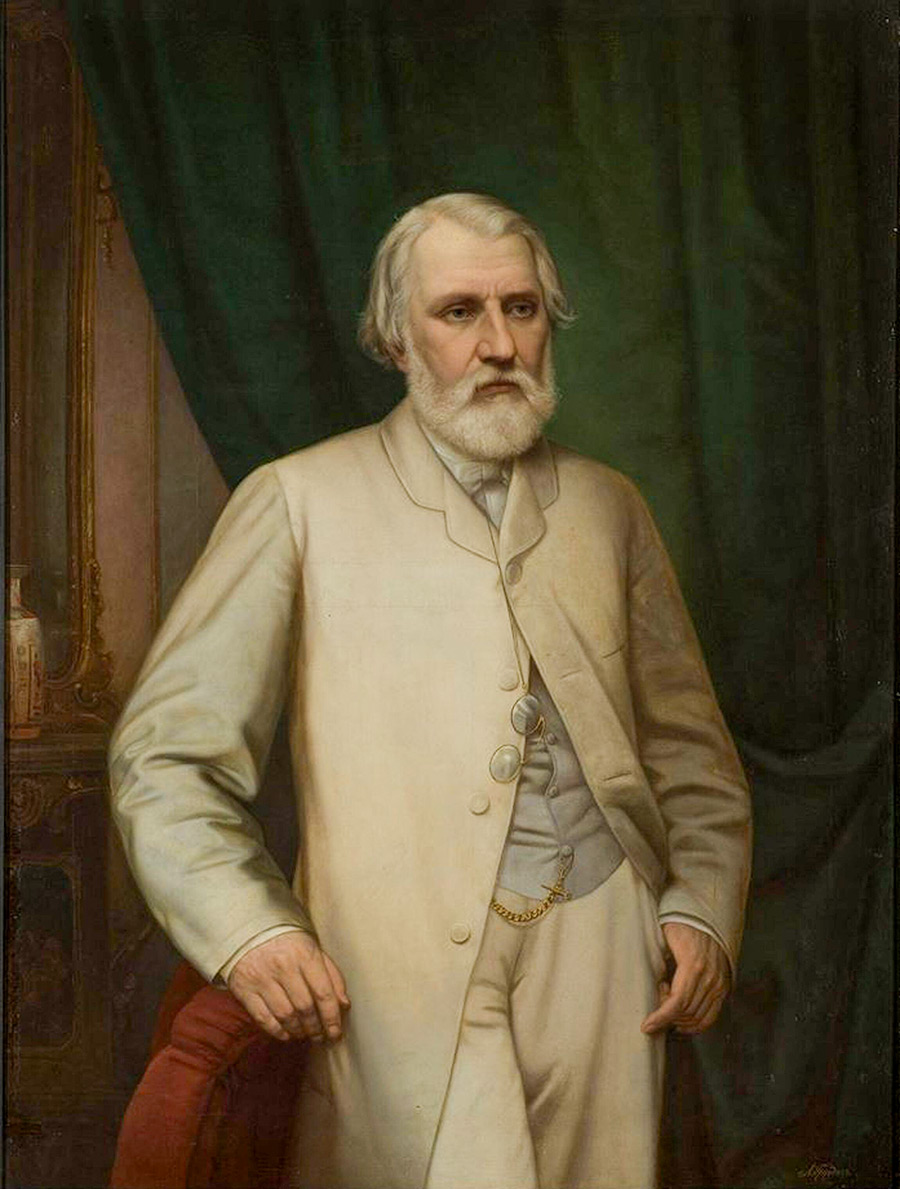

Dmitry Merezhkovsky, ‘The Resurrection of the Gods’

Another reflection on the theme of genius, but, this time, using Leonardo da Vinci as an example. If Pushkin believed that a genius can be young and lazy (talent alone being enough), then Merezhkovsky took art beyond ethics and morality. For him, a genius was an “immortal superman” as a result of his recognition, in whom God and the Antichrist are united. He is contradictory and all the ideas of his time are united in him.

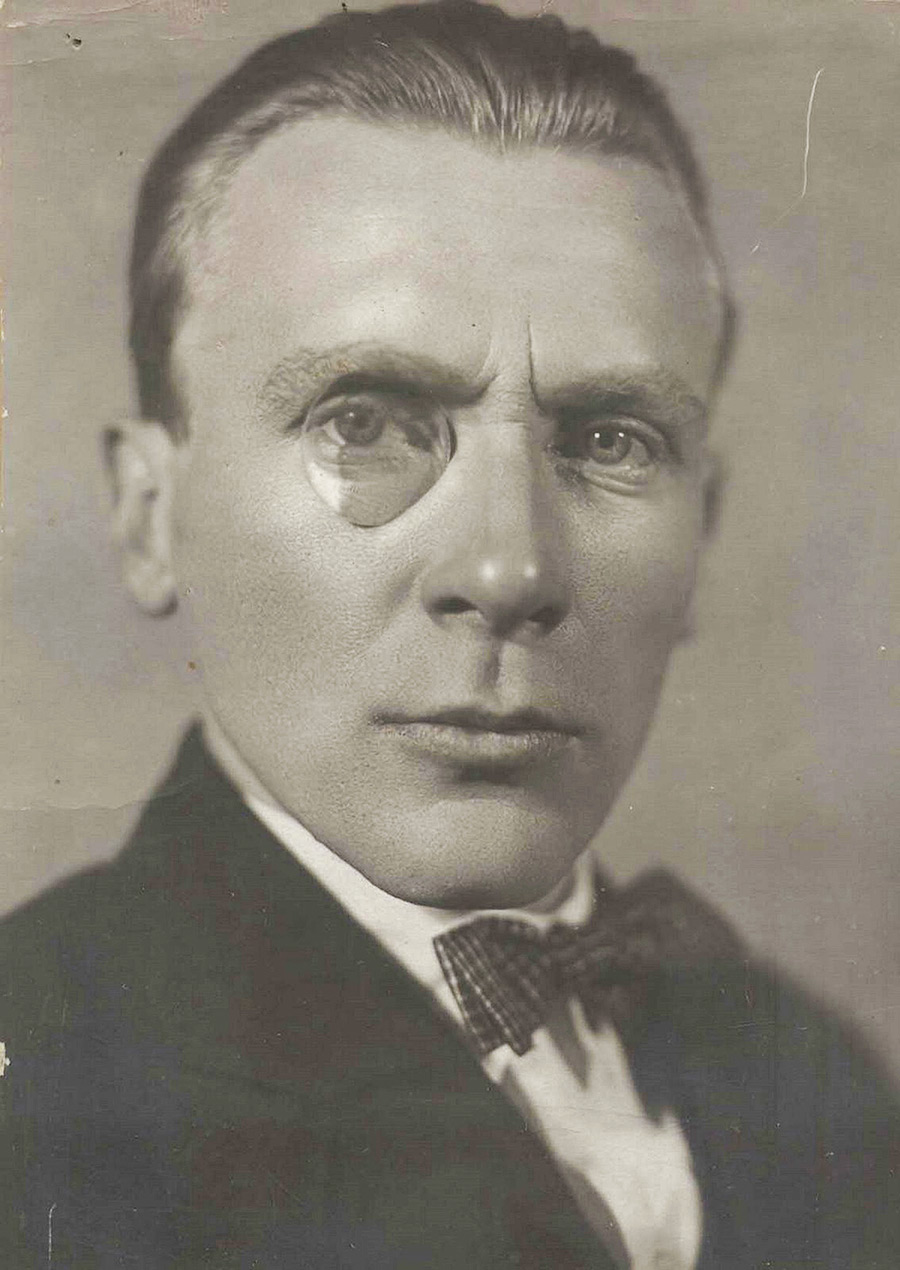

Mikhail Bulgakov, ‘The Life of Monsieur de Moliere’

Bulgakov wrote a fictionalized biography of the playwright in 1933 for an educational series titled: ‘The Lives of Remarkable People’ (conceived and started before the revolution and continued under the leadership of Maxim Gorky from the early 1930s). However, the main conflict of the work – the choice between the creative calling of a genius and public expectations, social order – seemed inappropriate to the editors in the context of the ideology of the young Soviet state and the manuscript ended up not being published. The book was eventually published in 1962, after the author's death.

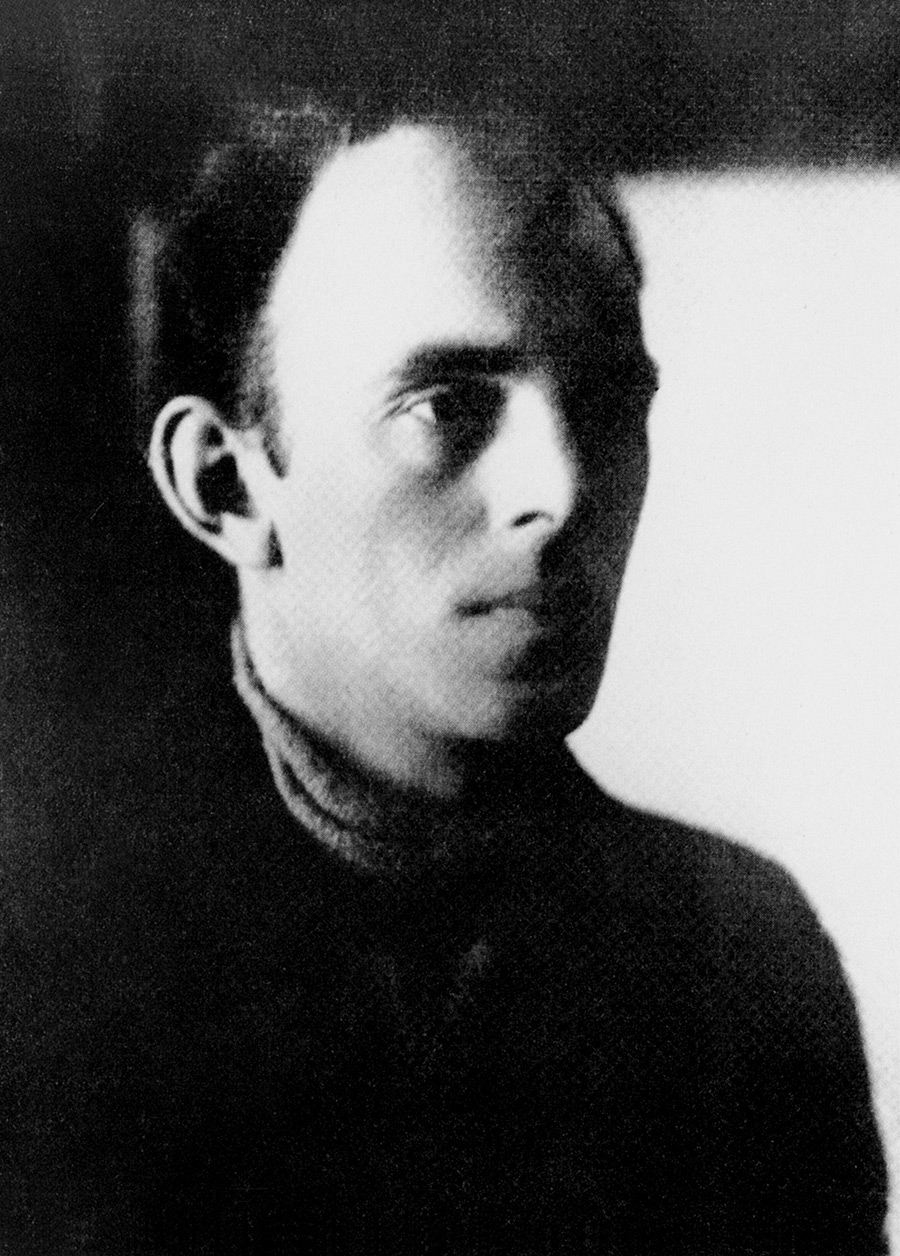

Osip Mandelstam, ‘Conversation about Dante’

In 1933, the poet learned Italian and devoured Dante. He read and reread ‘The Divine Comedy’. This work became for him a kind of optical device, through which Mandelstam peered into modernity. "It is unthinkable to read Dante's songs without turning them to modernity. (I believe) they were created for this. They are projectiles for catching the future. They require commentary in ‘Futurum’," he wrote once. Immediately after completing ‘Conversation about Dante’, he wrote the famous epigram on Stalin. Since then, literature and politics became one for him.