Did Leo Tolstoy copy ‘Anna Karenina’ from Flaubert's novel?

Scandal with ‘Bovary’

Flaubert's ‘Madame Bovary’ was published in Paris in 1856 and immediately caused a scandal. Already at the beginning of the following year, the author was put on trial for a novel about a pious girl, who becomes a bored wife trying to get her lover back who has lost interest and, in the end, kills herself. The book was called immoral. And a month later, triumphantly... lauded.

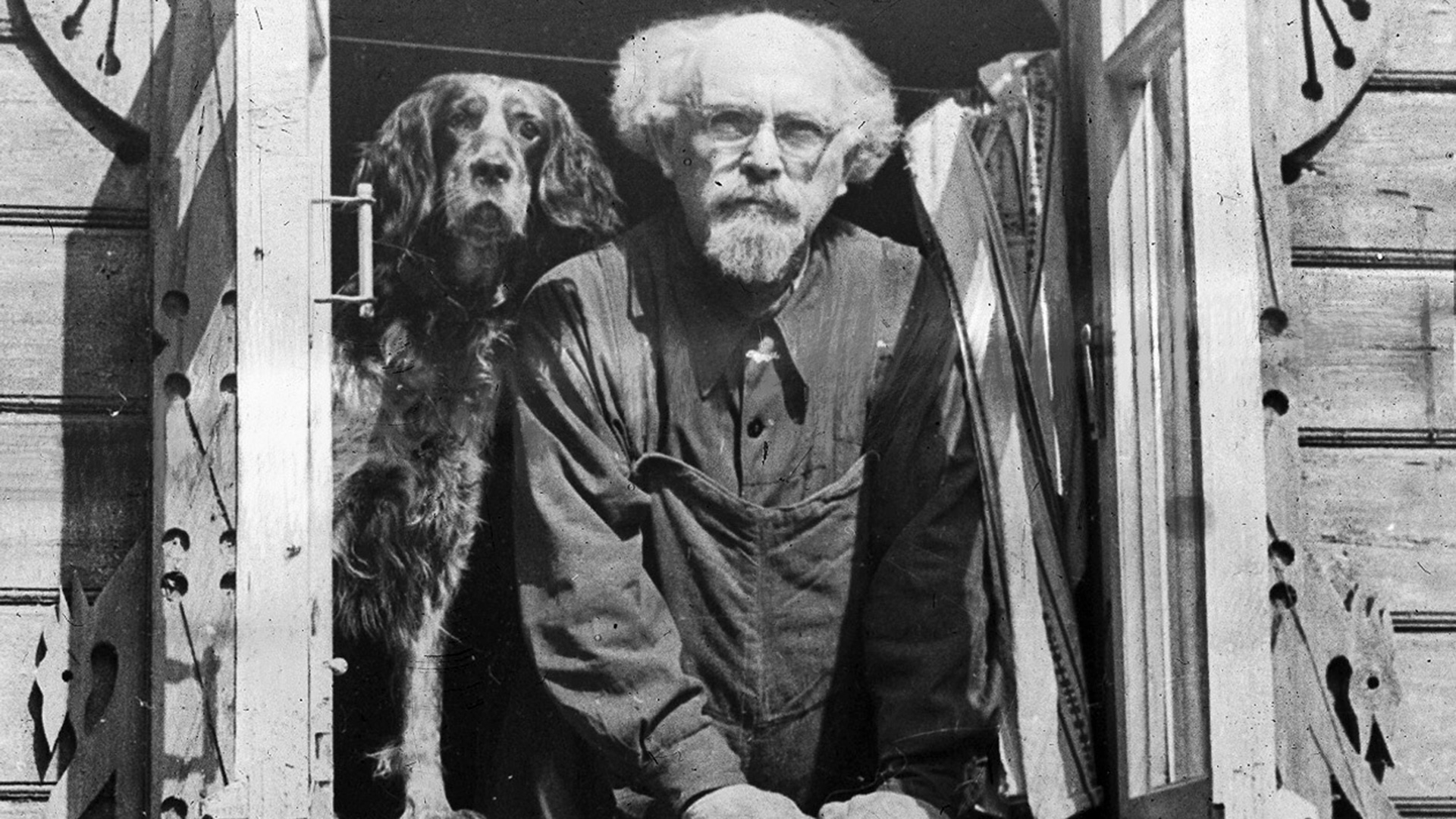

Leo Tolstoy arrived in Paris two weeks after the end of Flaubert’s trial. There, Tolstoy spent time with Ivan Turgenev. The Francophile Turgenev, of course, had already read ‘Madame Bovary’ and was absolutely delighted – he called the book the best work "in the entire literary world". It’s hard to imagine that Turgenev did not divulge all the details of the literary sensation to his friend. And even if Tolstoy had not read Flaubert's novel then, it is highly likely that he had heard about its plot. However, he stubbornly hid this fact – both Professor of Russian Literature Andrei Zorin and Tolstoy scholar Pavel Basinsky agree on this in their works.

Anna's prototype & work on the novel

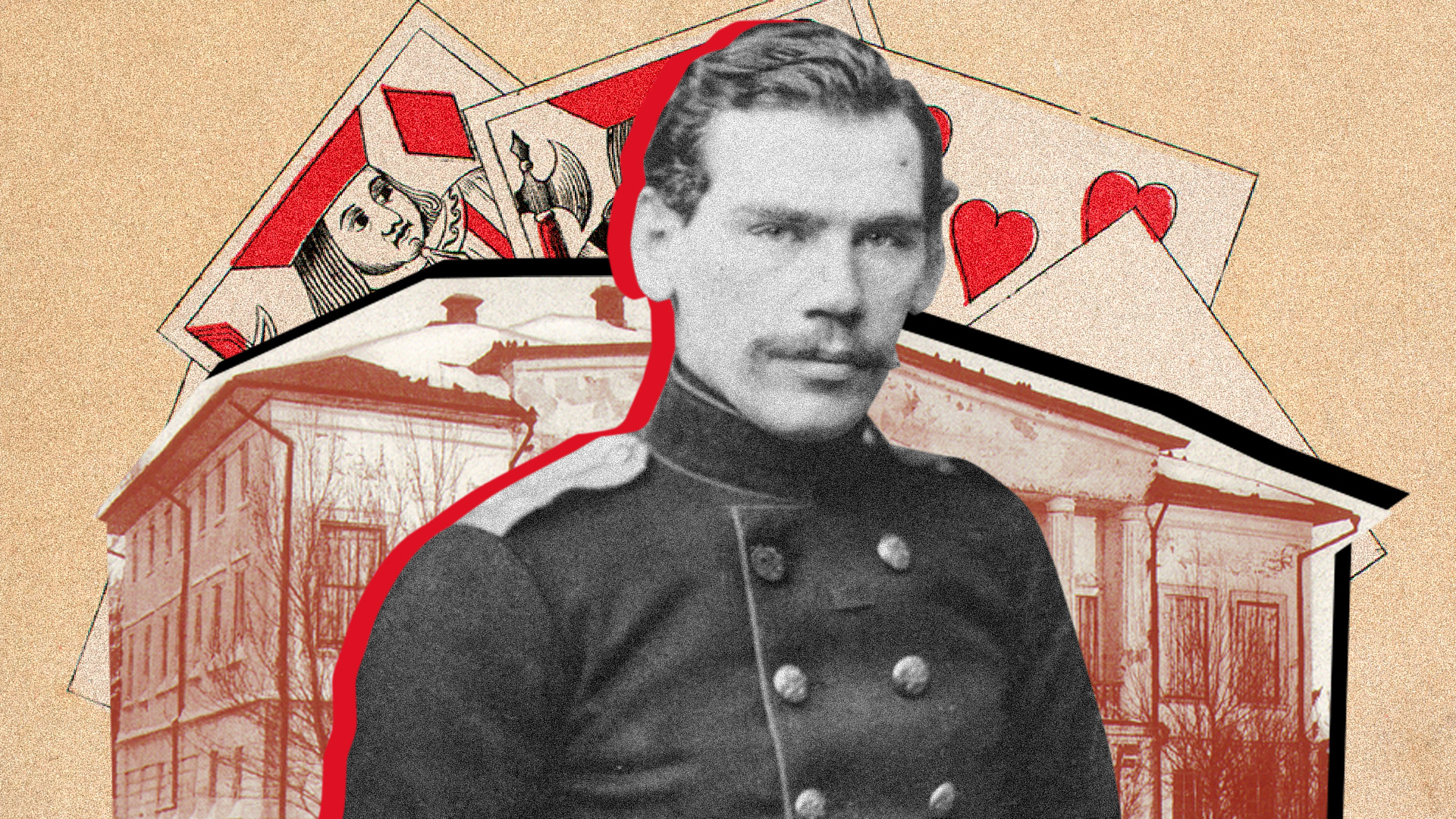

Literary scholars have noted that the first drafts of ‘Anna Karenina’, unlike, for example, the drafts of ‘War and Peace’, indicate that Tolstoy immediately imagined the logic of the plot and knew where he wanted to lead his characters. In early 1872, he even went specifically to look at the disfigured body of a certain Anna Pirogova, the housekeeper and abandoned lover of a landowner, who had thrown herself under a train after a breakup. This method of suicide was quite rare at the time and Tolstoy needed reliable details. Tolstoy wanted to give Anna's story the aura of an ancient tragedy. Therefore, in the interval between working on ‘War and Peace’ and ‘Anna Karenina’, he studied ancient Greek, in order to read the classics in their original language. The works of Sophocles and Euripides were supposed to help him find the right intonation. However, in the final text, the author abandoned the idea of justifying his heroine by evil fate.

Divorces & adultery in Russian society

Cases of open adultery and common-law marriages were not at all uncommon in Russian high society.

For example, it was known in court circles that Emperor Alexander II lived with Princess Ekaterina Dolgorukova and they had children together. Tolstoy's sister Maria Nikolaevna, meanwhile, separated from her husband and gave birth to a child in a common-law marriage with a Swedish Viscount named Hector de Kleen. Later, she repented and went to a monastery at the end of her life, but, in any case, she was never perceived as a pariah.

In addition, Elizaveta, the elder sister of Tolstoy's wife Sofya Andreyevna, divorced her husband and married her cousin, with whom she had been in an open relationship for some time before the divorce. Her social status did not suffer much.

That is, in life, such stories were common and were not strongly condemned. But, Tolstoy adhered to his well-known position – unequivocal condemnation. And, in his novel, he deliberately exaggerated the situation: society did not accept Anna’s extramarital affair.

Poet Nikolai Nekrasov, known for his love affairs, even ridiculed Tolstoy’s position in an epigram: “Tolstoy, you have proven with patience and talent that a woman should not “have fun” with either a chamberlain or an aide-de-camp when she is a wife and mother”.

Did Tolstoy ever read ‘Madame Bovary’?

Yes, he did. But, when exactly? It seems that the figures of silence here are more eloquent than the facts. In 1892, that is, 36 years after the publication of ‘Madame Bovary’ and 15 years after the release of ‘Anna Karenina’, Tolstoy dryly wrote to his wife that he was reading “Flaubert M-me Bovary has great merits and is, not without reason, famous among the French.” However, even if the master is being disingenuous and his ‘Anna Karenina’ was written in the wake of ‘Madame Bovary’, which he had read earlier, this does not in any way diminish the merits of the Russian novel. On the contrary: the living literary process is built on dialogue, debate, mutual citation, cross-references and interpretations. This works not only in relation to the literatures of the past (when postmodernists rewrite ancient plots, for example), but also in relation to the interaction of contemporaries. After all, as literary scholars believe, the contact of different literary points of view creates an environment for the development of great literature.