Why were peasant weddings in Russia truly MAGICAL?

Russian peasant weddings were not just a celebration, but a true magical rite, the purpose of which was to protect the newlyweds, ensure the birth of healthy children and the prosperity of the new family. Some of these traditions, in simplified forms, have even survived to this day.

Weddings would begin with matchmaking. This marked the beginning of a multi-day game, in which it was crucial to do everything "by the rules". Otherwise, people would think ill of the family or even bring misfortune upon the newlyweds.

Matchmaking & agreement

After the groom's family had decided which family to marry, matchmakers would go to the bride's home. These could be the groom's relatives, his godfather or a respected villager who knew the art of "beautiful speech". The matchmaking would usually take place in the evening. The journey to the bride's family, meanwhile, would always be a long, roundabout journey and conducted in silence. At the bride's home, the matchmakers would behave very politely and cautiously, referring to the bride and groom playfully and figuratively – ‘merchant goods’, ‘two lumps of dough’ and so on.

Nikolay Feshin. Cheremis wedding. 1908

Nikolay Feshin. Cheremis wedding. 1908

If the matchmaking was successful, the bride's family would visit the groom's home to assess the household. Sometimes, the groom's parents would borrow utensils, grain and livestock from neighbors for this day, creating an image of complete prosperity. After this, the dowry would be negotiated. If all negotiations were successful, the betrothal would take place in the bride's home. The girl's parents would prepare a feast, light candles and pray. Then, the matchmakers would put on mittens or take a pie in each hand and clap them together, signifying the final agreement on the marriage. From that moment on, the bride was considered "betrothed".

After the betrothal, in many villages, the bride would be "veiled", that is, covered with a kerchief or scarf. She would begin to wail, mourning her maiden life, preparing her dowry and rarely showing her face outside until the wedding. "Some girls remain a bride for a little over a week, but they're so overworked that they lose their voice and their knees are bruised," said a peasant woman from the Starorussky district.

Every day, the bride would sew her trousseau and prepare gifts for the groom's family. Her girlfriends would help her and sing songs. In some regions, the groom could visit the bride during this time, bringing her and her girlfriends nuts and gingerbread. His friends might also join him. The girlfriends would sing cheerful songs, while the groom's friends laughed and joked and the bride wept bitterly.

Bachelorette & Stag Parties

In many villages, a banya (bathhouse) would be heated before the bachelorette party. The bride would be dressed in a long robe and her hair would be braided. The braid could contain needles, thorns and threads – it would usually be completely tangled, making it more difficult to unbraid. And this would cause some of her hair to fall out. Afterwards, the bride, covered with a scarf to protect her from the evil eye, would be led to the banya, with twigs from a broom marking the way, each with a ribbon tied around it.

Alexey Korzukhin. Hen Party, 1889, Russian Museum

Alexey Korzukhin. Hen Party, 1889, Russian Museum

Three or four girls would undress and wash with the bride. The boys, meanwhile, would crowd around the banya, climb onto the roof and sing ditties and jokes. After the banya, the bride would be richly dressed and presented to the groom. He could yank her braid hard, step on her foot (until it bled) or ask whose daughter she was. After the bride's answer, the groom would kiss her.

The bride was then presented with gifts, while she treated the guests and, after their departure, she would "say goodbye to her braid", which would be unbraided again. In many villages, the bride wore her hair loose until her wedding.

A final evening, a bachelor party, was also arranged for the groom, for which his friends and relatives would typically gather. The banya would also be heated, blessings given and singing took place. After the bachelor party, the groom could go with his friends to the bride's bachelorette party and then host her friends with gifts.

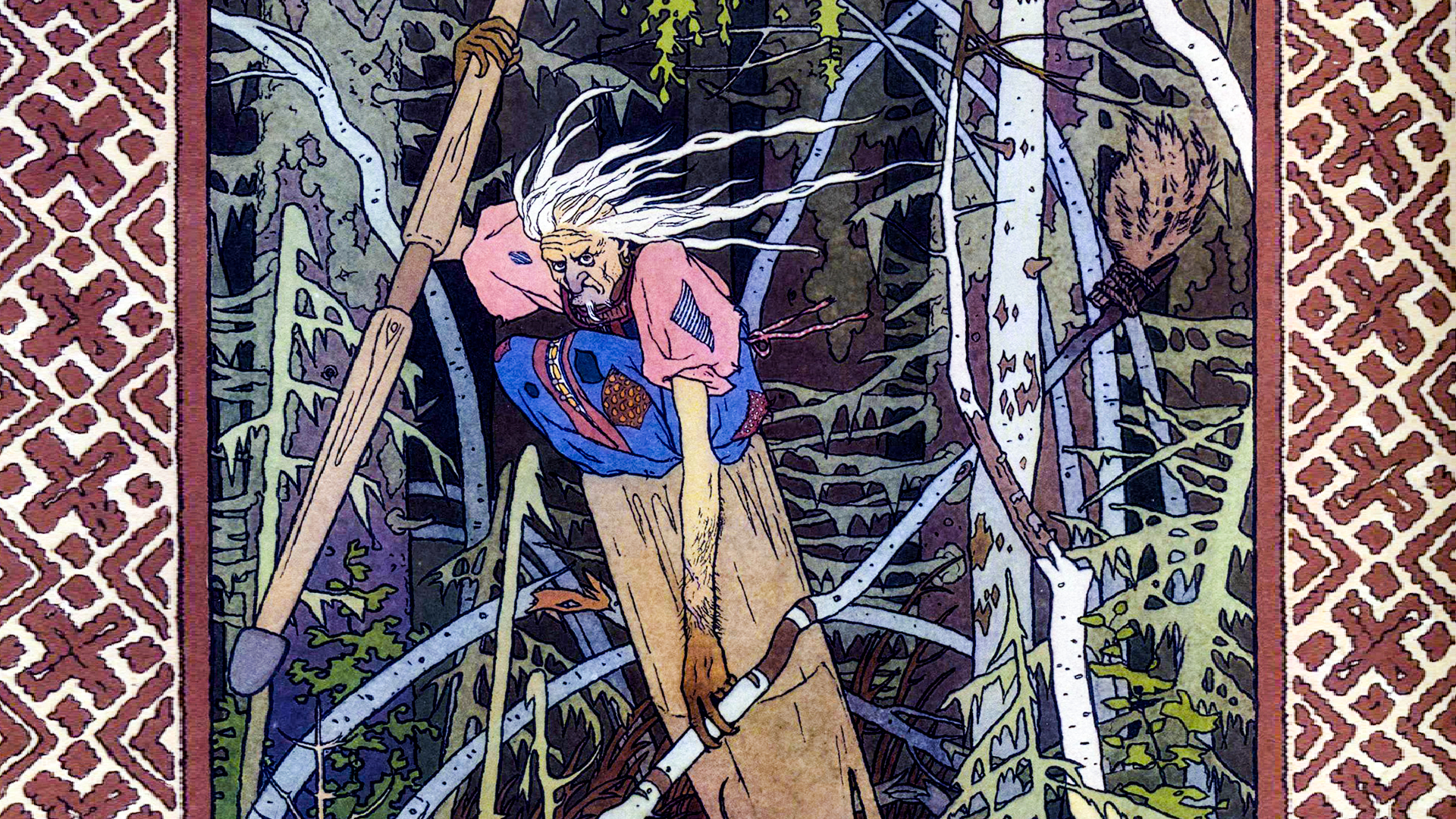

N. P. Bogdanov-Belsky. "The Wedding", 1904

N. P. Bogdanov-Belsky. "The Wedding", 1904

Wedding

Naturally, this was the most important and eventful day. In the morning, relatives and neighbors would gather at the groom's house, arriving in elegantly decorated carts. The best man (the man closest to the groom) would be girt with a towel, presented with a whip, bread and an icon – he became the chief organizer of the wedding. Then the wedding procession would depart to fetch the bride.

Along the way, various obstacles would be set up for the procession, demanding a ransom (blocking the path, lighting fires, firing guns), while matchmakers scattered flaxseed.

Meanwhile, the morning in the bride's family would begin with lamentations. The bride's girlfriends would help the bride dress, sing songs, unbraided her hair for the last time, dressed her, covered her with a large kerchief, and left her to wait for the groom or best man. The meeting of the groom's procession was like a performance. The bride's relatives closed the gates and locked the doors. The best man had to knock for a long time, pretending to break down the gates. Riddles were posed to him, and he answered them.

This could be followed by the purchase of the bride, the bride's braid and the seating arrangements at the table. Then, the newlyweds would be seated at the table on a fur coat turned inside out (a symbol of wealth and fertility). The bride and groom would then be blessed by the bride's parents.

Vasily Maksimov. The Sorcerer's Arrival at a Peasant Wedding, 1875

Vasily Maksimov. The Sorcerer's Arrival at a Peasant Wedding, 1875

Afterwards, the groom would place the bride in the carriage and the wedding procession would set off for the church. Along the way, the planned obstacles would again be encountered.

Feast

After the wedding, the matchmaker would braid the bride's hair into two braids and style it, placing a ‘povoinik’ (a married woman's headdress) on her head and covering it with a kerchief. The newlyweds would then ride in the same carriage to the groom's home. Along the way, they would again be asked to pay a ransom and, at the house, the horse and carriage typically would pass through burning straw gates to ward off the evil eye.

At the house, the couple would be met by the young man's parents, often dressed in fur coats with the fur inside out. They would hold bread and an icon for blessing. The newlyweds would typically be blessed on a fur coat, skin or rug and showered with rye, oats and hops. They would be given milk, honey and cranberries to drink and they would nibble on a loaf of bread. At the wedding table, the newlyweds would sit on fur coats or pillows, eat with the same spoon and drink from the same cup. And the meal would always be hearty, during which the bride was no longer allowed to lament. They would all sing songs of praise to the newlyweds, joking and laughing at the mummers.

After the feast, the newlyweds would be put to bed in a separate room. The groom's female relatives would lie on the bed, demanding a ransom from the bride. Afterward, the bride would remove the groom's boots, finding money in them. The newlyweds would then be left alone for about half an hour. After said half hour, the matchmaker would call the newlyweds out for tea. And, after tea, everyone would go to bed.

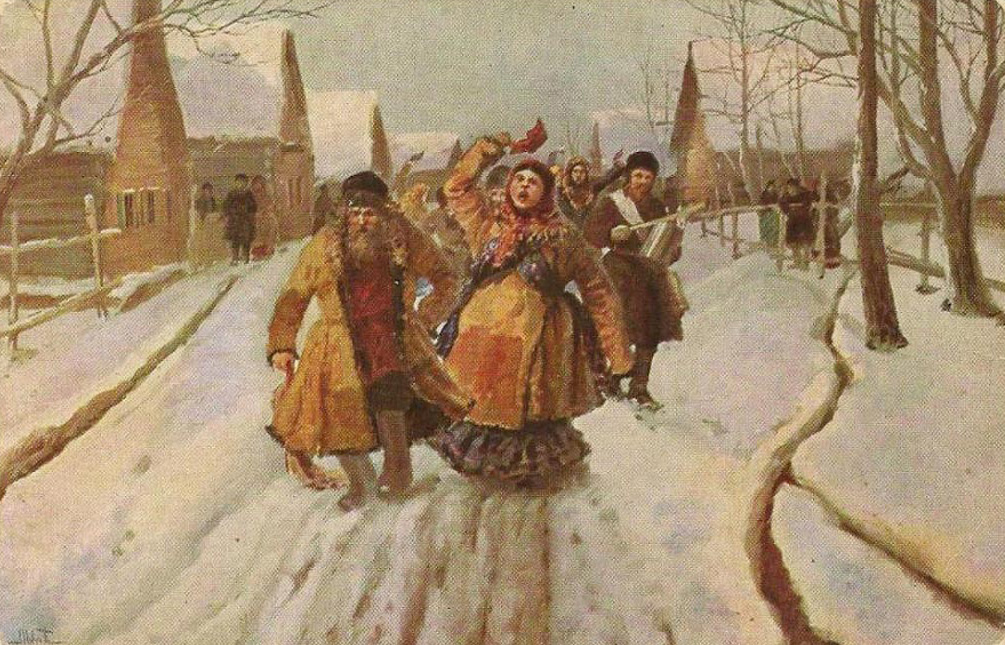

I.M. Lvov. Wedding Festivities. Postcard published in Moscow in 1912

I.M. Lvov. Wedding Festivities. Postcard published in Moscow in 1912

Post-wedding rituals

The following morning, the newlyweds would be awakened by smashing pots against their bedroom door (symbolizing lost virginity) and banging buckets. Everyone drank tea, after which the guests scattered trash and feathers around the hut and the newlyweds were expected to sweep the hut. The bride would be given a chopped-off broom. Then she would fall at her mother-in-law's feet and beg her to teach her how to sweep – her mother-in-law would give her a proper broom. Money would also often be thrown on the floor along with the trash.

After cleaning, she would be sent to fetch water. The entire village would gather to watch the young wife draw water. They would interfere with her, empty buckets of water, trying to splash the newlywed and each other. The matchmaker would hand out pies and the young wife would "ransom the spring" by throwing money into the water.

Afterwards, they would have a feast, ride in decorated tarantasses or sleighs through the villages and sing love songs.

The wedding would end with a visit to other relatives. After this, the wedding would be considered over and the young wife would return to her daily work routine. And so it continued until the early 20th century.