How ‘matchmakers’ became the main marriage broker in merchant Russia

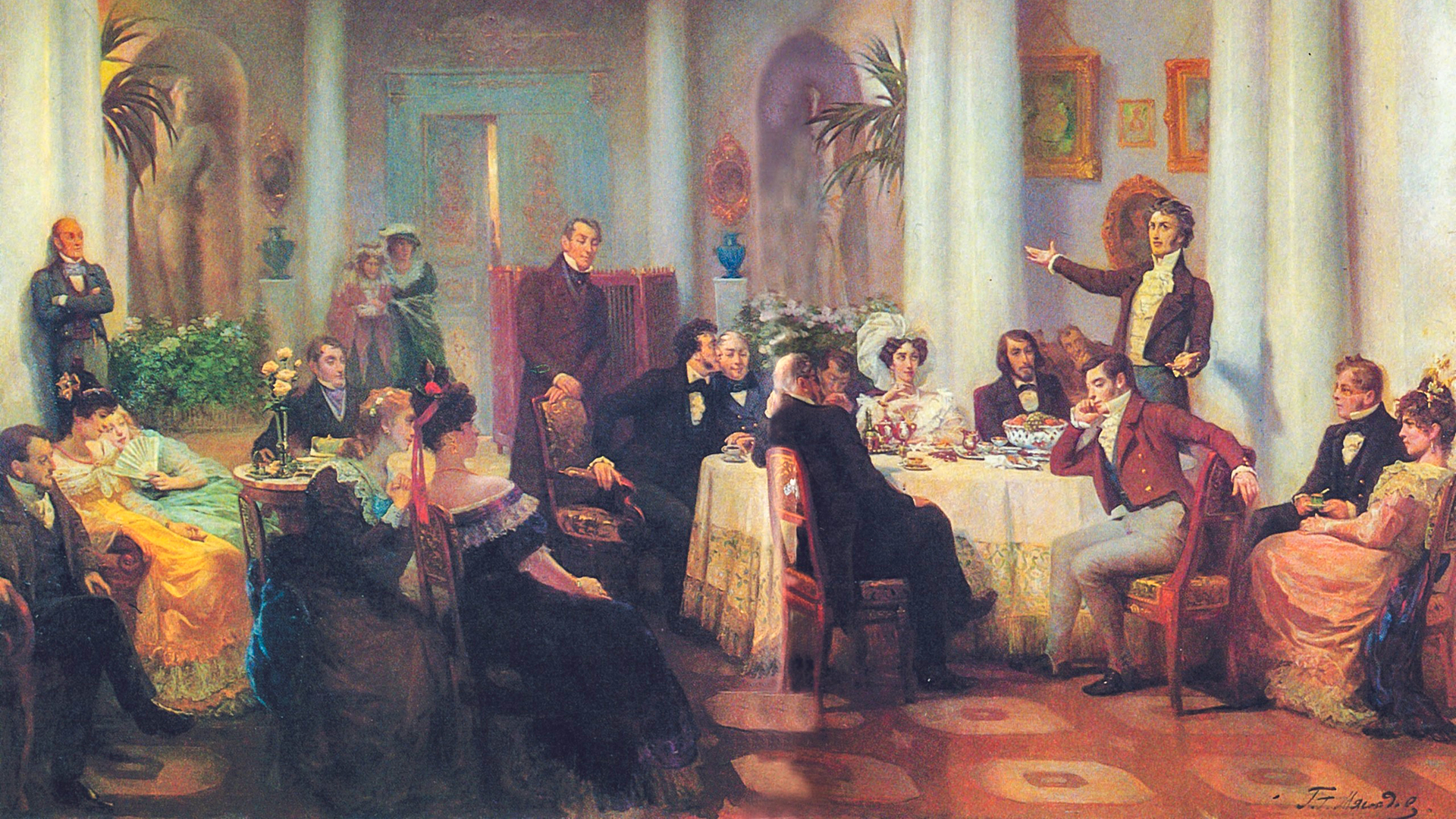

Among the nobility, the role of matchmaker was often played by relatives or socialites and potential brides and grooms had the opportunity to meet at balls. Bourgeois and working-class youth, meanwhile, could meet independently in urban spaces: in church, at work or during festive celebrations. However, in the closed, traditional environment of Russian merchants, a matchmaker was indispensable. With rare exceptions, merchants' daughters were forbidden to leave the house, so finding a groom was only possible through a matchmaker from a ‘brachnoe agentsvo’ (‘marriage agency’).

Mikhail Larionov. Matchmaker. Costume design for the ballet “THE JOKE”. 1915

Mikhail Larionov. Matchmaker. Costume design for the ballet “THE JOKE”. 1915

A matchmaker was usually a mature woman, often a widow, who knew life and people well. She collected and provided families with information about potential brides and grooms, balancing the fine line between advertising and credibility. A bride might be described not as "sickly", but as "gentle", not as "poor", but as "from a good, but not wealthy family, but modest and a skilled craftswoman". Regarding the groom, instead of "he drinks", he might be described as "cheerful". Instead of "old" he might be described as "respectable, well-adjusted".

If the groom wanted a brunette, he was promised a black-haired beauty, even if the bride was a downright blonde. Sometimes, after the wedding, it would turn out that the girl's hair had simply been heavily dyed with soot.

A still from Konstantin Voinov's film "The Marriage of Balzaminov" (1964)

A still from Konstantin Voinov's film "The Marriage of Balzaminov" (1964)

Since it was difficult for a stranger to enter a merchant's house, matchmakers resorted to various tricks. An experienced matchmaker would befriend the servants, extracting information about the hosts' personalities and inclinations from the maids and cooks. Only then, disguised as a seller of lace or needlework items, would she infiltrate the family, knowing how to make the right impression on the hostess.

Serving a single family took a significant amount of time and money. Therefore, the fees of good matchmakers were high. For example, in Ostrovsky's play ‘The Marriage of Balzaminov’, the matchmaker asks for 2,000 rubles, signing a written agreement to ensure receival of payment.

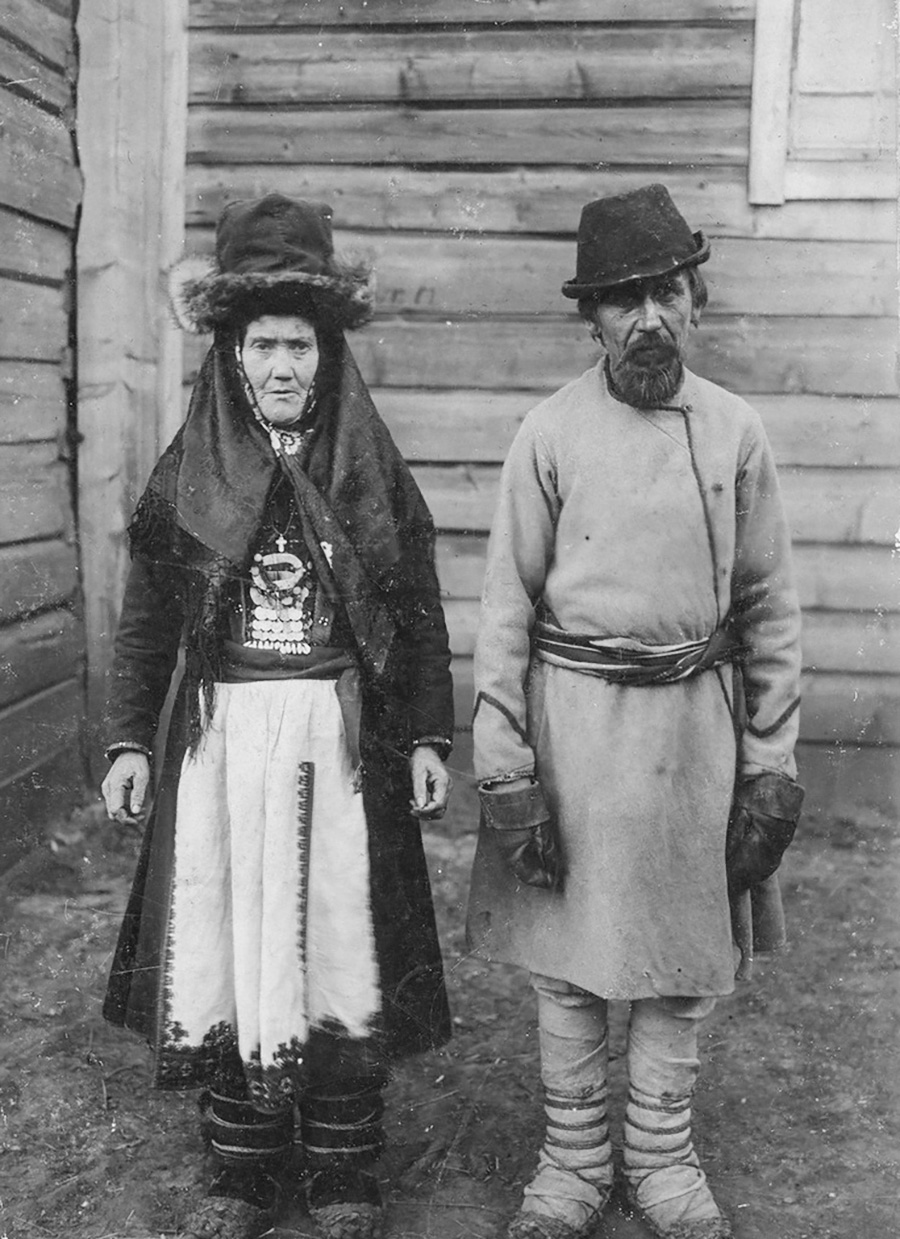

Matchmaker. 1910 - 1915 Republic of Mari El

Matchmaker. 1910 - 1915 Republic of Mari El

However, all the information gained enabled the matchmaker to navigate the other person's wealth as if it were her own and, subsequently, negotiate the dowry – one of the key elements of the marriage contract – knowing the cost of each item and being able to negotiate the best terms.

The matchmaker also arranged and organized the ‘smotrinny’ (‘viewing’) – ie. the first visit of the groom's family to the bride. The bride was dressed, seated in the red corner and expected to demonstrate submissiveness and modesty, keeping her eyes downcast. The matchmaker then directed the performance, advising when to stand and when to walk to demonstrate her stature and health. She also acted as a legal advisor: she guaranteed that the marriage was permissible from a church perspective (for example, that the groom was not a bigamist).

Wedding. The matchmaker speaks with the groom's parents. 1910. Kazan Province.

Wedding. The matchmaker speaks with the groom's parents. 1910. Kazan Province.

The matchmaker's job was not only lucrative, but also dangerous. If the groom or his family felt cheated, the matchmaker could easily be beaten. So, the risk of losing not only her fee, but also potentially getting bruises was part of the profession.

However, by the end of the 19th century, society had changed and young people now had the opportunity to communicate directly, which made the matchmaker's profession almost redundant. However, in patriarchal environments (for example, in religious communities), matchmakers still exist.