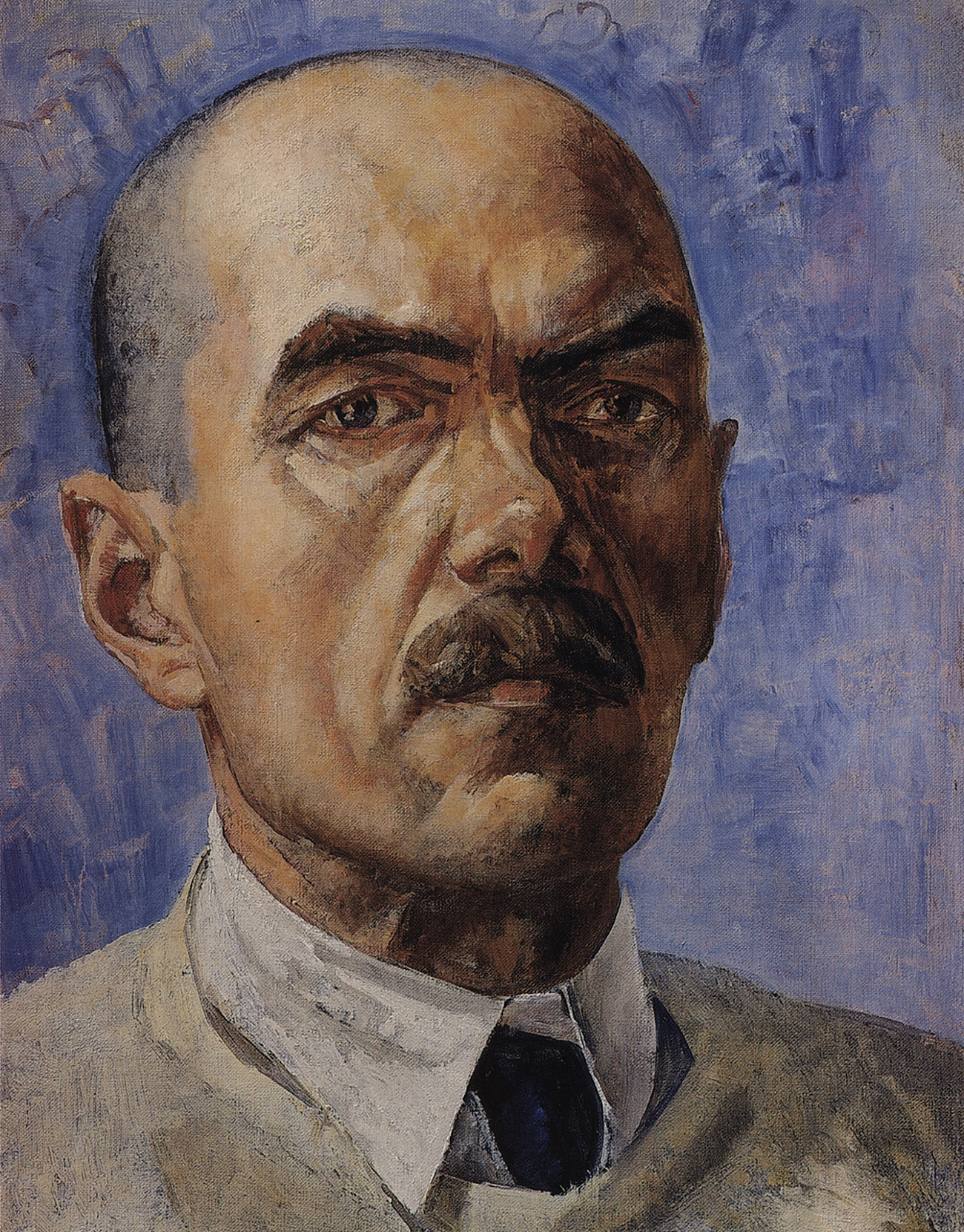

What's going on in this painting by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin?

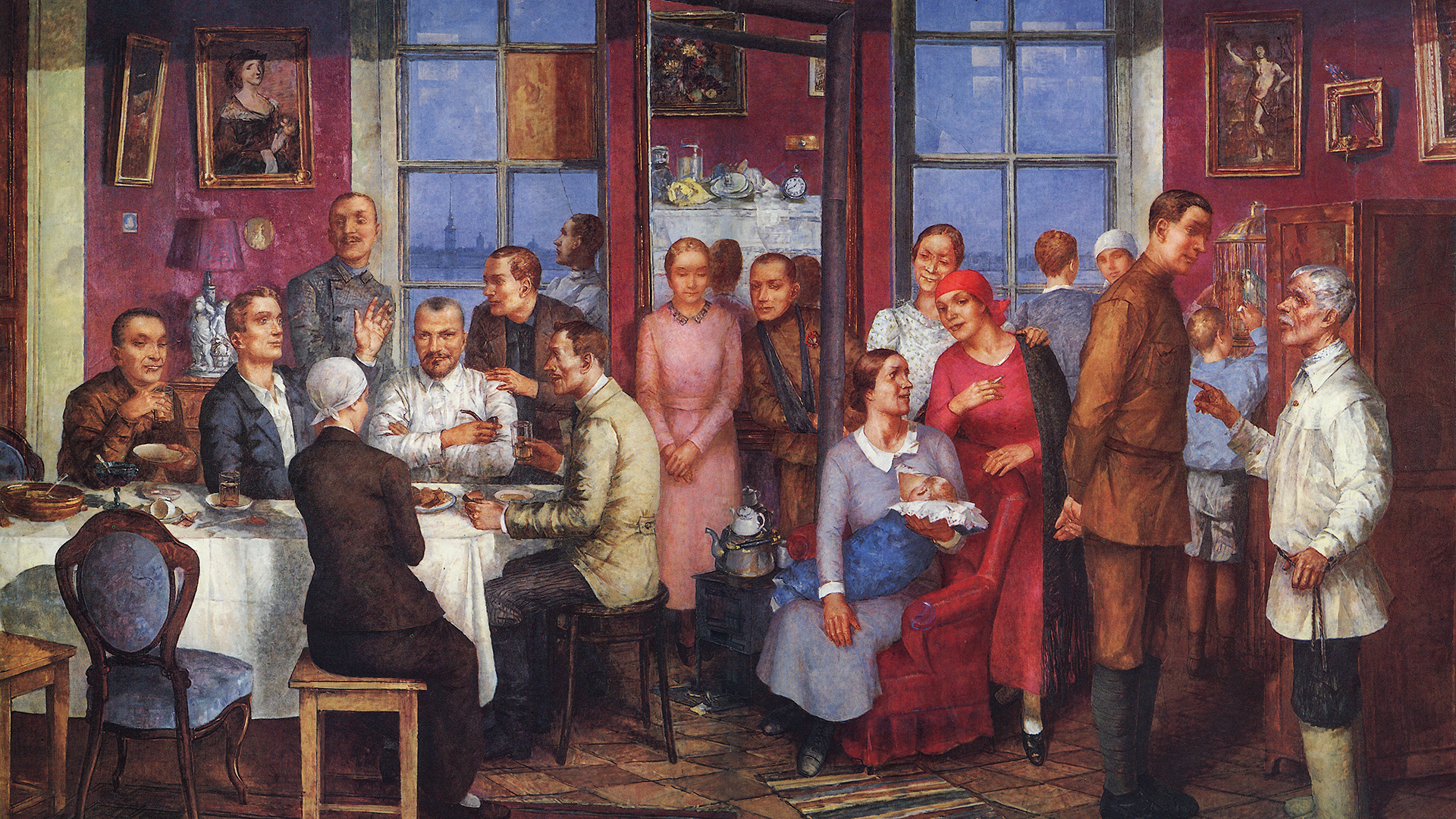

The irony of fate: Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin struggled to capture the painting's original theme on canvas. The artist was supposed to paint a piece about the Civil War for the ‘Industry of Socialism’ All-Union Exhibition. He wanted to depict the moment when the old owners were being evicted from their apartment and new, Soviet people moving in. However, the work was slow – the artist had no desire to depict overtly bad characters (which is precisely how the "bourgeoisie" was supposed to appear). He, instead, decided to expand the story of the apartment's change of ownership and focus on what happened afterward. Thus, in 1937, ‘Housewarming (Workers' Petrograd)’ was created.

Apartment with a View of the Neva

"About 20 people gathered in a large room with windows overlooking the Neva River – the owners of the house and their guests, simple, good people. In their very selection, in their facial expressions, their clothing, their movements, I show both the traces of the Civil War left behind and the beginning of a new, socialist construction project," Petrov-Vodkin wrote.

The plot of ‘Housewarming’ unfolds in 1922. The battles of the Civil War have ended and peaceful life has begun once again. A working-class family has moved into an apartment in the center of Petrograd (now St. Petersburg). The former owners are nowhere to be found – apparently, they left Russia. The paintings on the walls remind us of them – perhaps including a portrait of the apartment's former owner or a parrot in a cage, left at the mercy of the new tenants, being fed sugar by a boy.

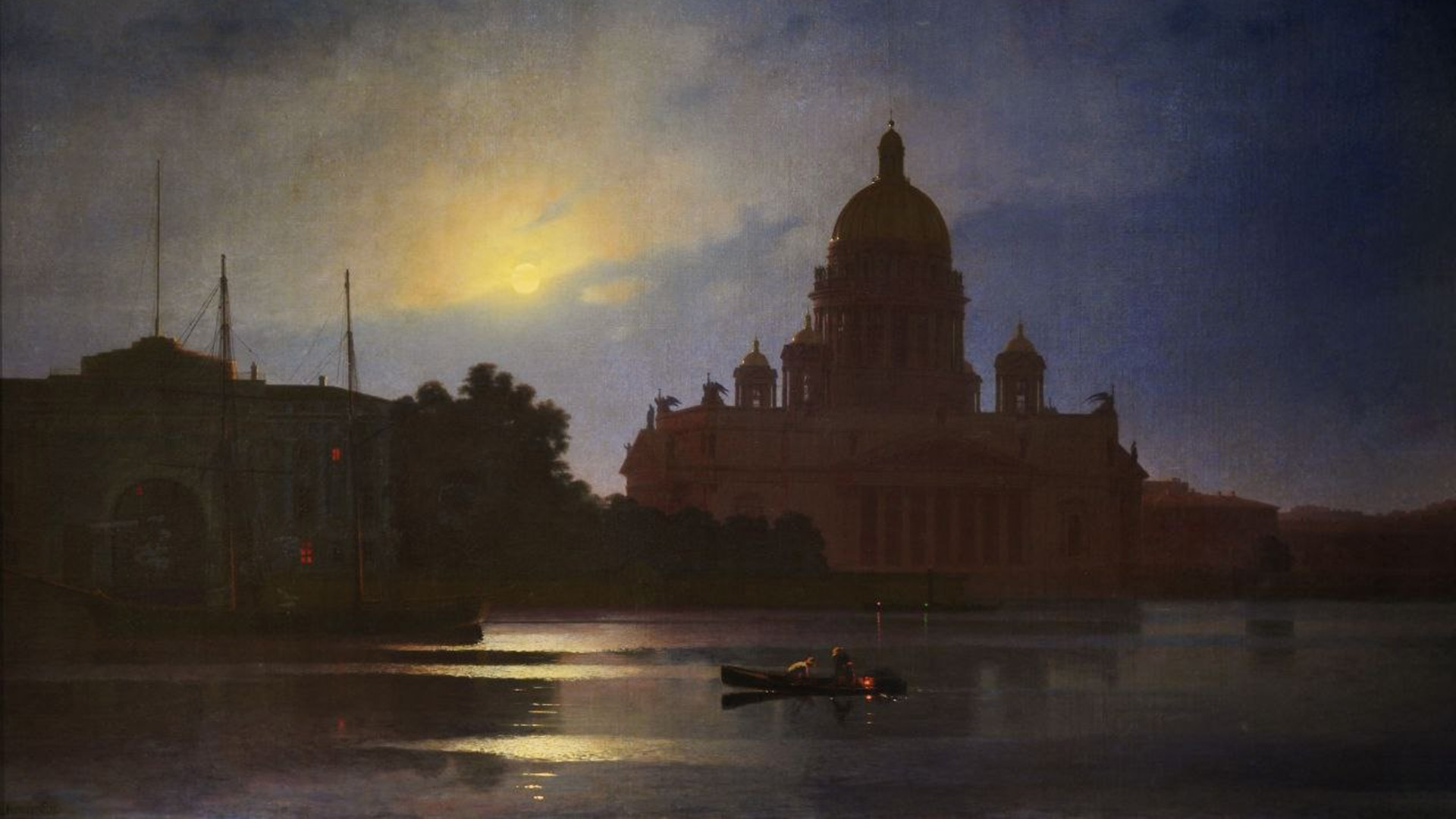

The once large apartment has been converted into a communal apartment – a table has been pushed right up against the interior door. The room's window overlooks the Peter and Paul Fortress: if we compare it with a city map, it appears that the painting's characters are celebrating their housewarming in a building on Millionnaya Street or Palace Embankment – right next to the Winter Palace. This is the very heart of the city, where, before the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, members of the imperial family, courtiers and aristocrats lived, embassies were housed and expensive apartments were rented out.

New Life

The painting is densely populated with characters, making it seem as if there's literally no room to move in this large room. Conversation is underway at the table – everyone is so engrossed in it that they've forgotten the simple food on their plates. A young man is talking and gesturing passionately. A man in a uniform jacket is listening in. He stands over the right shoulder of the apartment's owner, a man in a white shirt holding a pipe. A little further away, his wife is feeding their child in a red armchair, also engrossed in conversation with a girl in a red headscarf, who is smoking a cigarette.

Behind the women, a wounded Red Army soldier is attempting to woo a shy girl in a pink dress. He appears to have recently returned from the front – his arm is in a sling and the ‘Order of the Red Banner’ hangs around his neck. A commissar, meanwhile, is listening attentively to his interlocutor, an elderly man in felt boots.

The new owners have already begun to settle into the apartment: a rustic rug has been thrown on the parquet floor. Roughly made stools sit alongside elegant chairs, while the icon frame is empty – only a willow branch remains in the place of the icon.

The storm of the Civil War left its mark, too: a kettle is warming on a potbelly stove – the central heating in Petrograd was out at the time. The broken windowpane is boarded up with plywood. Only the landscape outside the window remains unchanged – a "bright white night".

No hints

It seemed Petrov-Vodkin had completely transferred his vision to the canvas – the war was over, the country had returned to peacetime. "These are the ones who will destroy the devastation and create everything that befits a socialist reality," the artist explained. But, the exhibition committee rejected the painting. Three times. This was an unpleasant surprise for the artist.

The issue wasn't so much his work as the realities of the time. Those who had moved into vacated apartments yesterday could tomorrow find themselves as "enemies of the people" and disappear without a trace. And the housewarming scene left an ambiguous impression. And the People's Commissariat of Heavy Industry of the USSR, which was organizing the exhibition, could not tolerate any allusions.

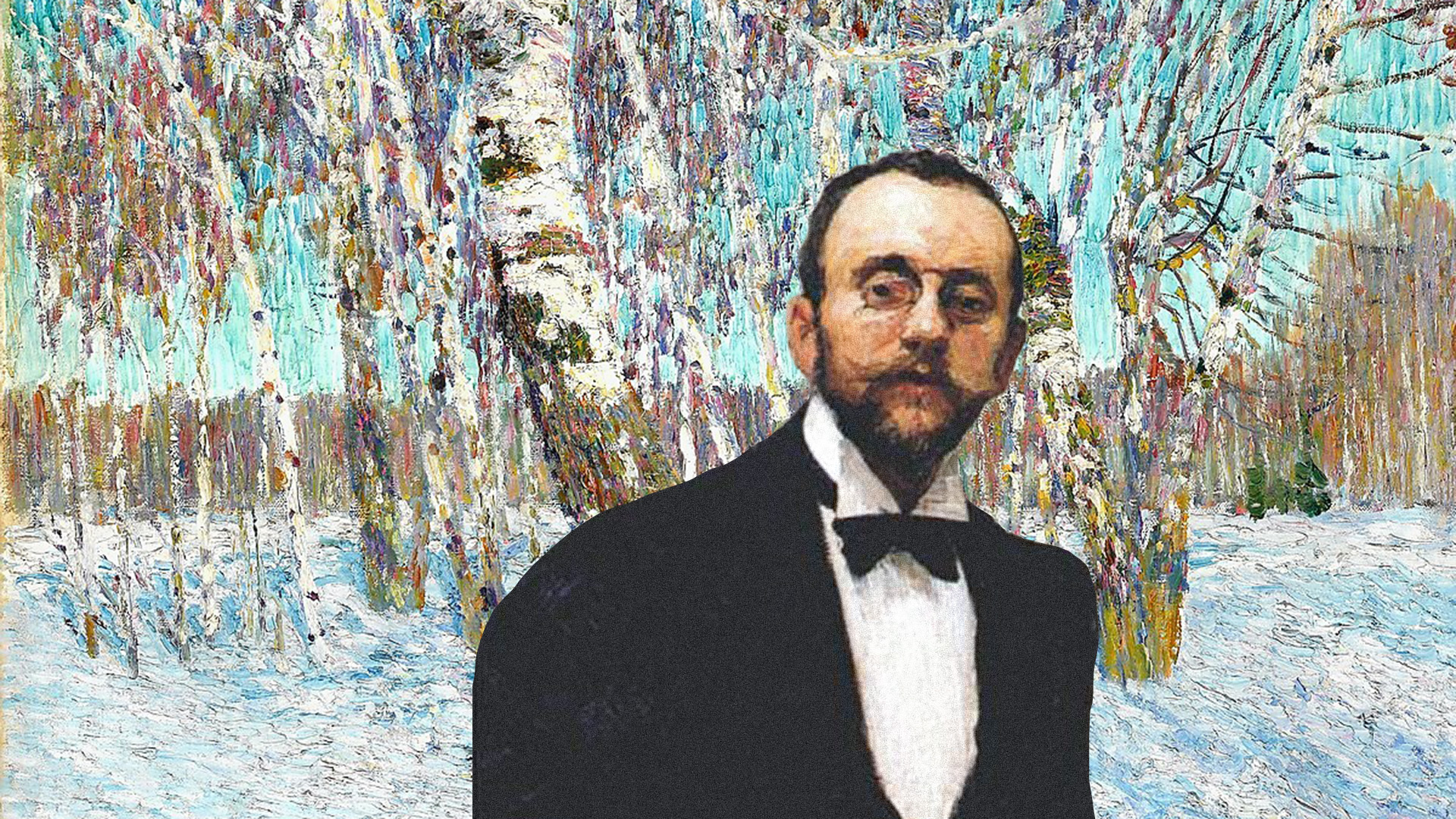

The ‘Industry of Socialism’ All-Union Exhibition opened in Spring 1939 in Moscow on Frunzenskaya Embankment. More than 1,000 works were selected for it. Among the exhibitors were Igor Grabar, Alexander Labas, Sergei Gerasimov, Arkady Plastov, Konstantin Yuon, Martiros Saryan and Boris Ioganson. Petrov-Vodkin did not live to see the exhibition open; he died on February 15, 1939. His painting ‘Housewarming’ was only first seen by the public in 1965, at a major exhibition of the artist's work at the Central House of Writers in Moscow.