Why was water carrying an important profession in Tsarist Russia?

"The Moscow water carrier is a most interesting rogue. Firstly, he is full of self-esteem, as if he knows he's carrying the elements in his barrel. <…> Secondly, he fears no one: not you, not the magistrate, not the police officer! Even if you are promoted to general, he won't be afraid of you. If he doesn't bring you water and forces you to go to the tavern for a glass, you can't protest. "There's nowhere and no one to complain to – that's just the way things are," wrote Anton Chekhov in ‘Fragments of Moscow Life’. However, things weren't always so rosy.

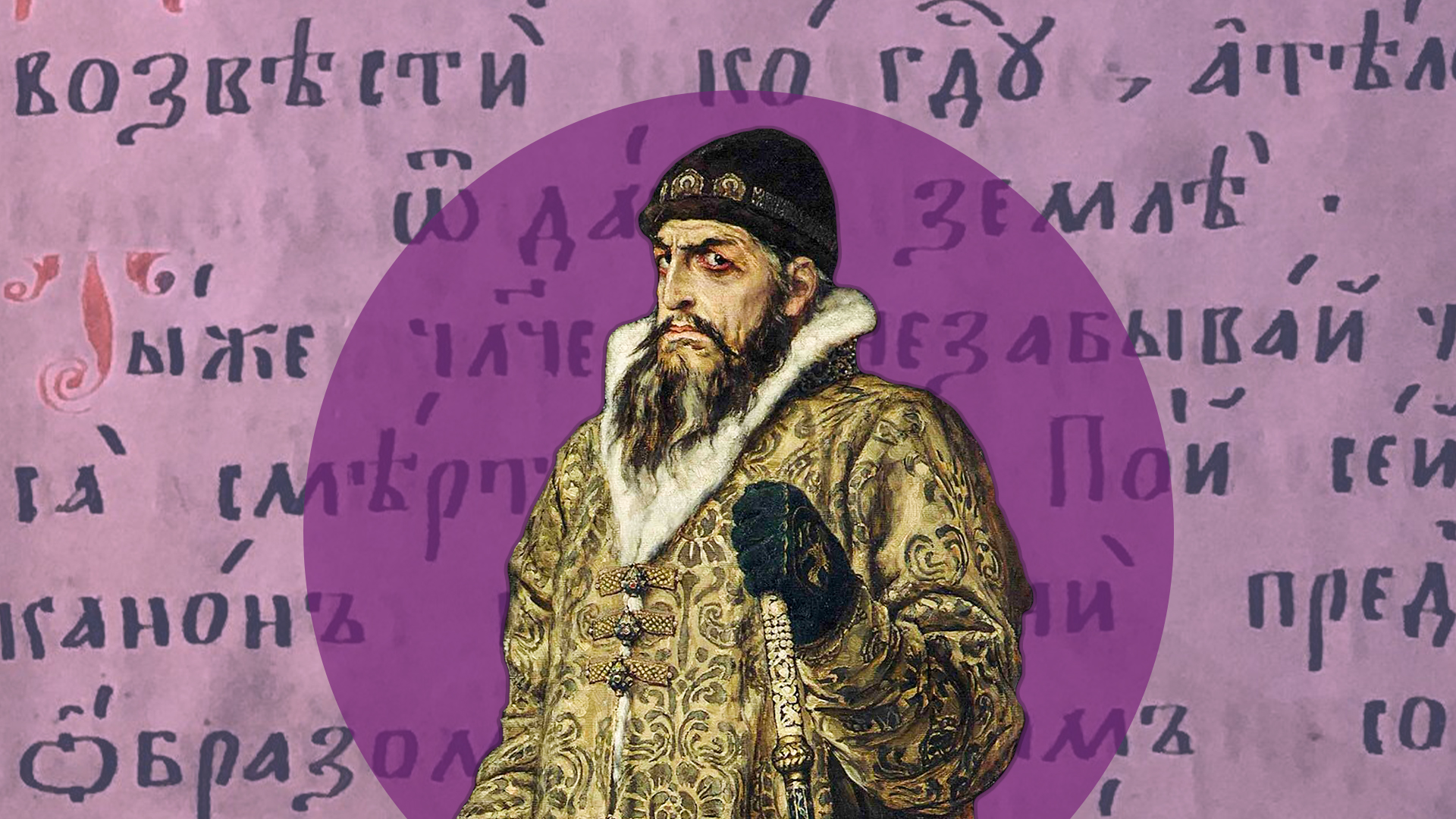

A water carrier at the end of the 19th century

A water carrier at the end of the 19th century

A centralized water supply was rare in the 19th century. The vast majority of the population, from tenement dwellers to shopkeepers and artisans, received their water from water carriers' barrels. They, in turn, drew water from the city’s rivers, wells and fountains.

A water carrier's workday began before dawn. He was usually a physically strong, resilient man. His main tools were a barrel (sometimes two), mounted on a sled in winter and a cart in summer. Such a barrel could hold 20-40 buckets worth (approximately 240-480 liters). His arsenal also included a pouring trough with a groove, which was placed on the back of the cart and buckets on a yoke for delivering water directly to apartments.

Water carriers. 1897 - 1909

Water carriers. 1897 - 1909

The work was physically hard. In winter, water carriers had to cut holes in the ice and work in the bitter cold; in summer, they had to lug full buckets up steep stairs in the scorching heat.

Water carriers would often form teams and could assign specific areas or houses to themselves. The fee for their services was low, but stable and usually charged monthly.

In large cities such as Moscow and St. Petersburg, there was a "gradation" of water quality. A "river" water carrier carried water directly from rivers and canals (the Moskva River or the Neva River). Such water was considered low-quality, turbid and suitable mainly for household needs, such as washing floors and doing laundry. The "spring" or "fountain" water carrier drew water from famous city springs or fountains (for example, from the famous Moscow "fountains" of the Mytishchi water supply system). Clean, clear and "tasty" spring water commanded a higher price and was mostly used for cooking and drinking.

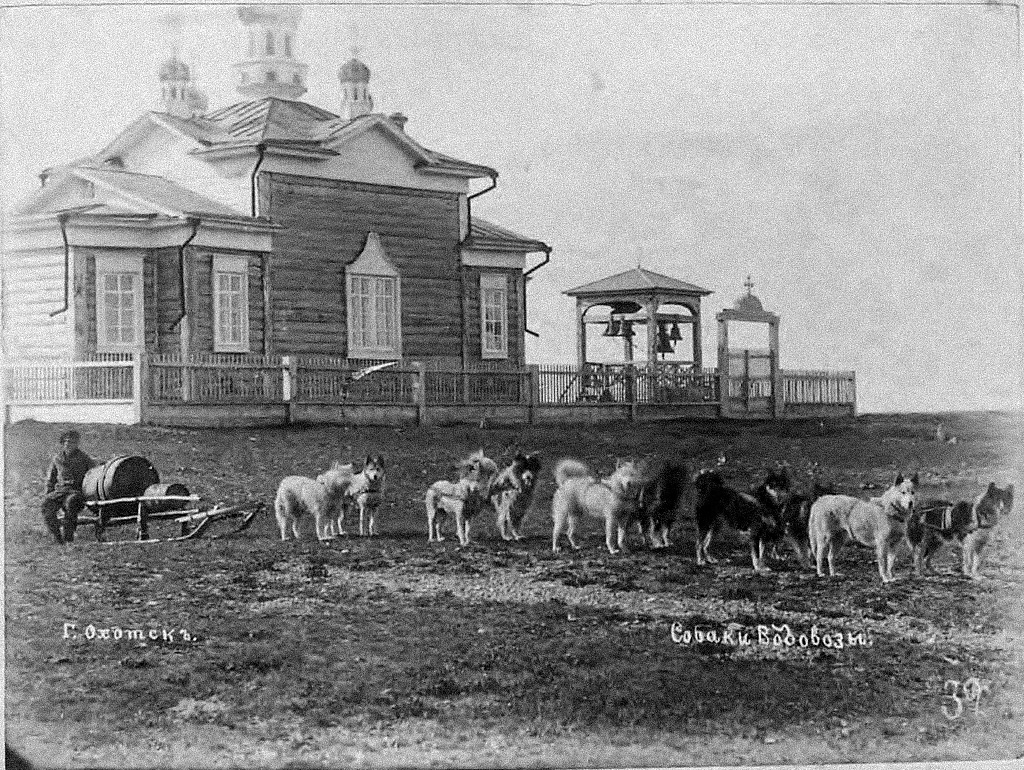

Water carrier dogs. Church of the Transfiguration of the Savior, Primorsky Region, Okhotsk

Water carrier dogs. Church of the Transfiguration of the Savior, Primorsky Region, Okhotsk

The water carrier's cry: "Vody-y-y!" or the slap of a bucket rim against a barrel was one of the city's most recognizable sounds, comparable to the cries of delivery men or the ringing of cabbies' bells.

With the widespread installation of centralized water supply systems in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the profession of water carrier slowly began to disappear. Wherever a faucet appeared, the need for a man with a barrel disappeared.