Gender – one of the most mysterious grammatical categories in the Russian language

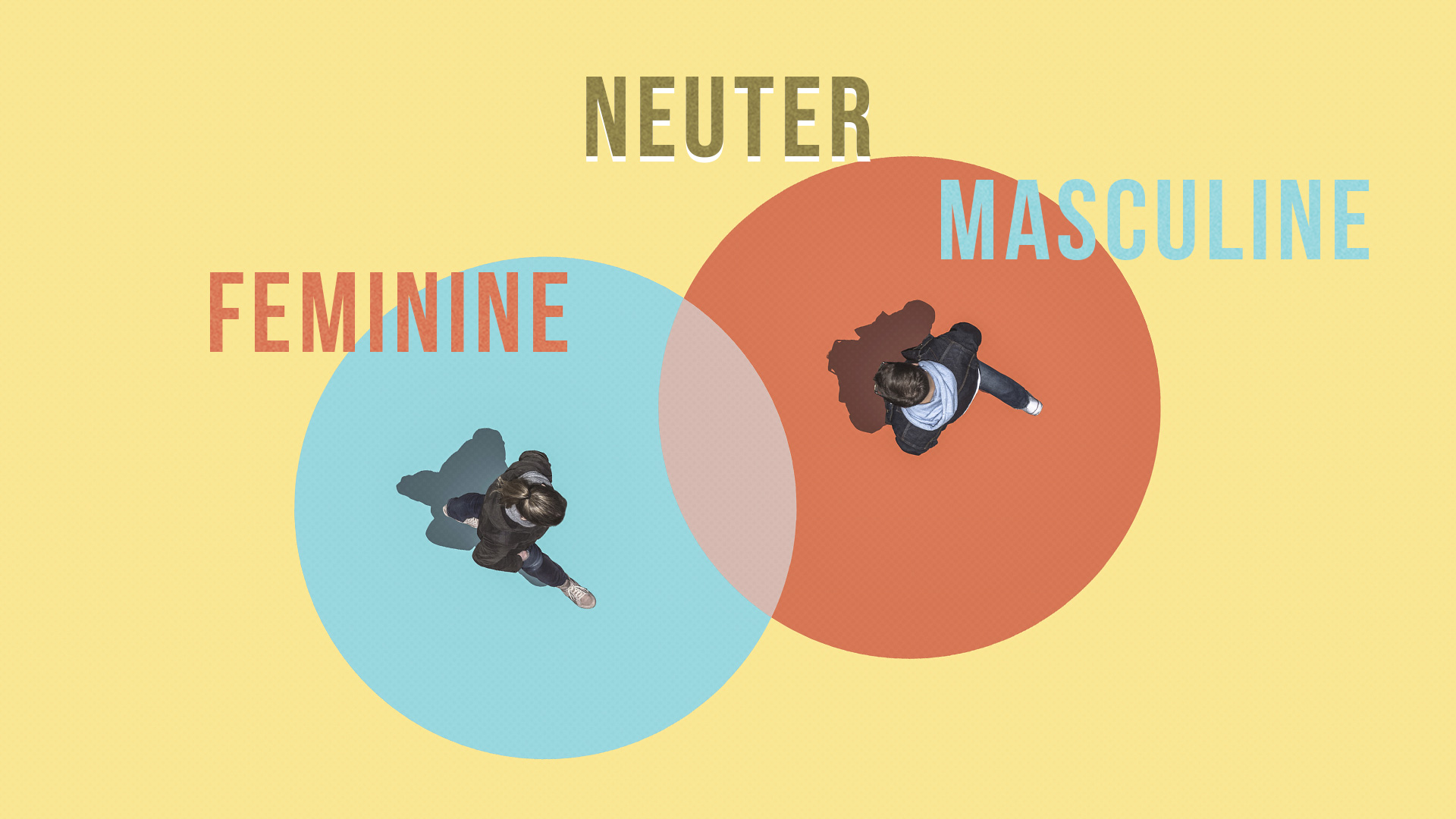

There are three genders in Russian: masculine, feminine and neuter. Masculine nouns make up about 46% of the modern language, feminine nouns 41%, while neuter nouns 13%.

How words were assigned a specific gender

Linguists have different opinions regarding the origin of grammatical gender.

“Proponents of the natural theory link the origin of the gender category directly to biological sex,” Andrey Gorshkov, an editor at Gramota.ru, says.

But, there are adherents of the morphological theory, who explain gender through the development of the language's grammatical structure.

With animate objects, it's all intuitive: ‘женщина’ (‘woman’) is feminine, ‘мужчина’ (‘man’) is masculine. Many animals even have different gender-related forms: ‘козел’ – ‘коза’ (buck/doe), ‘лошадь’ – ‘конь’ (mare/stallion).

The neuter gender, however, was associated with inanimate and abstract objects, such as ‘море’ (‘sea’), ‘небо’ (‘sky’), ‘поле’ (‘field’).

At the same time, some words in Russian have changed their gender over time: for example, the words ‘лосось’ (‘salmon’), ‘путь’ (‘way’/’path’), ‘лебедь’ (‘swan’) and ‘Суздаль’ (‘Suzdal’, a city outside Moscow) were originally feminine, but are now masculine. And on the opposite, ‘тень’ (‘shadow’) was once masculine, but now it’s feminine.

“This may be more evidence that grammatical gender itself is not related to the meaning of words and, consequently, not related to sex,” Andrey Gorshkov insists.

How to determine the gender of nouns

Since, most of the time, the grammatical gender of nouns is not directly related to the word's lexical meaning, the assignment of a noun to the masculine, neuter or feminine gender must be simply memorized.

And, often, the gender category in Russian and other languages (for example, German) does not match.

However, even native speakers have difficulties determining gender. For example, with borrowed words (‘кофе’ – ‘coffee’), abbreviations (‘НАТО’ – ‘NATO’) or compound words (‘интернет-страничка’ – ‘web page’).

Word endings can indirectly help in determining gender, although there are cases that don't fit any rules (for example, animate masculine nouns with ‘-а’ and ‘-я’ endings).

Masculine | Feminine | Neutral |

Zero ending | Ending in ‘-а’ and ‘-я’ | Ending in ‘-о’ and ‘-е’ |

|

|

|

There are many exceptions, and words ending in ‘-ь’ (soft sign) also pose a problem. They can be either masculine (‘конь’ – ‘stallion’) or feminine (‘лошадь’ – mare).

Common gender

In addition to masculine, feminine and neuter nouns, Russian has a group of words classified as ‘common gender’. This includes animate nouns that can refer to either a male or a female person, although they outwardly resemble feminine nouns more. For example, ‘умница’ (‘smart person’), ‘судья’ (‘judge’), ‘сирота’ (‘orphan’).

There are also words denoting professions that linguists define as candidates for common gender: ‘новый врач пришел’ or ‘новая врач пришла’ (these phrases determine by gender – it’s seen in an adjective and a verb, but both mean ‘the new doctor has arrived’, though the second version is more common in colloquial speech).

Due to the unnatural sound of such constructions to the Russian ear, there is a tendency to create feminized forms from profession names: ‘поэт’ – ‘поэтесса’ (‘poet’ - ‘poetess’), ‘продавец’ – ‘продавщица’ (‘salesman’ - ‘saleswoman’) have become the norm. But, today, feminists are inventing forms that still sound ridiculous: ‘режиссер’-’режиссерка’ (‘director’).