Why were European tutors revered in Russia?

Who were they & why were they needed?

In the Russian nobility of the 18th-19th centuries, tutors and governesses played a key role in home education. Let's remember Pushkin's hero Eugene Onegin: At first, Madame was in charge of his upbringing, then she was replaced by Monsieur l'Abbé, who taught the child "everything jokingly", without strict morals, and took him for walks in the Summer Garden of St. Petersburg.

Governesses typically began teaching children from 5-7 years old. Their duties included teaching foreign languages, secular manners, music, drawing, as well as the basics of history and geography.

Then, boys aged 7-9 were transferred to tutors. They not only continued teaching languages and other subjects at a deeper level, but also cultivated masculine qualities in them – curiosity, intelligence and courage. Girls, meanwhile, would remain with their governesses, but their program also became more serious.

By the age of 10, primary education was considered complete and hired teachers were added to the faculty. As Alexander Chatsky sarcastically noted in Griboyedov's ‘Woe from Wit’, the nobility hired them "in greater numbers, at a lower price".

How it all began

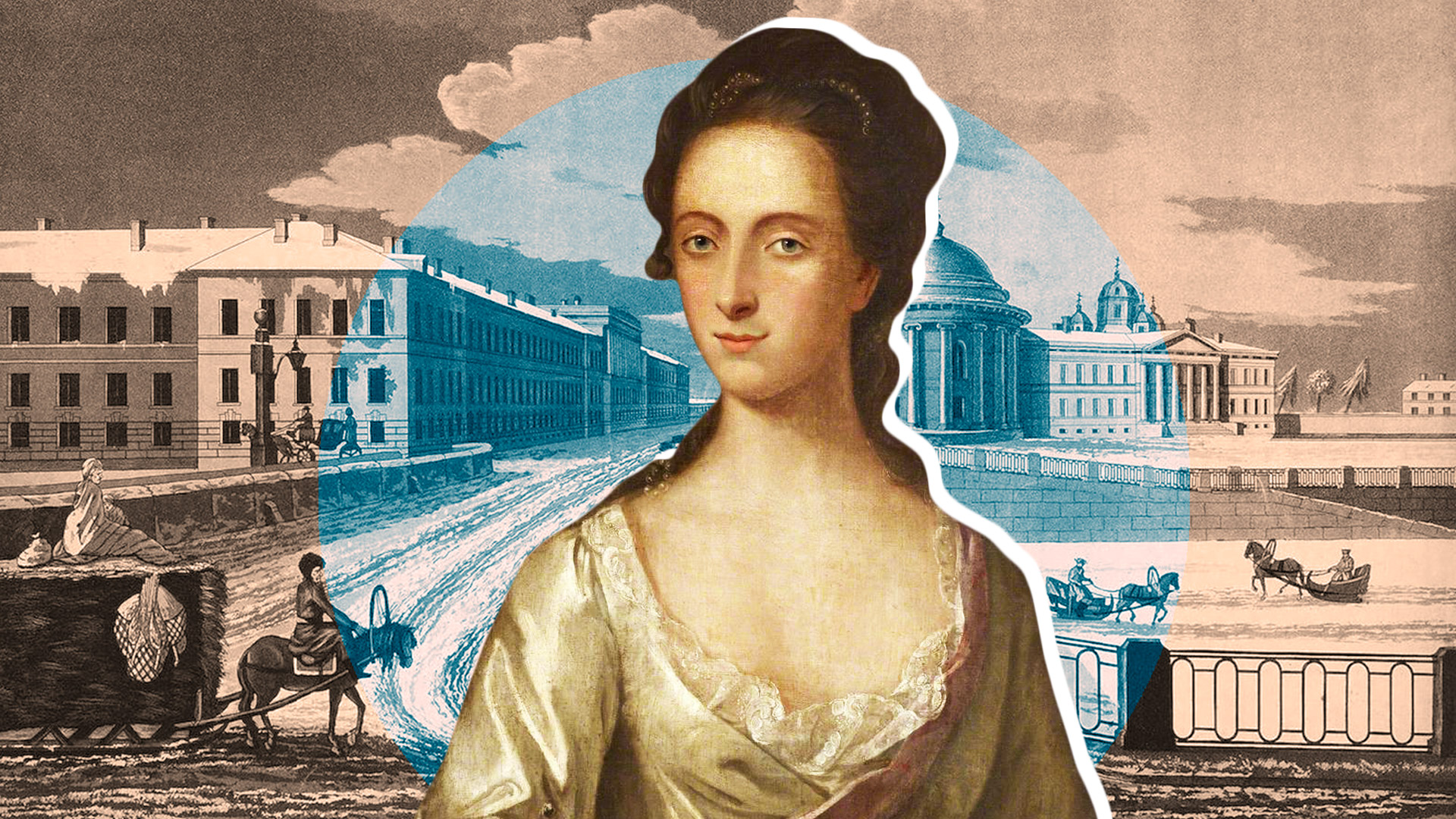

The first tutors appeared in Russia in the 18th century as part of the focus on European education. Their main task was to teach, first of all, secular manners and foreign languages. Because of this, there were often poorly educated people with a dubious past (cooks, tailors, soap makers) among them, whose competence was often left unevaluated. In 1757, Empress Elizabeth I even issued a decree requiring all foreign tutors to pass exams at Moscow University or the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. However, this rule was violated everywhere. Yet, despite this tendency, there were also highly educated people among the tutors. For example, Baroness Preiser, the governess of Ekaterina Dashkova, an associate of Catherine II and one of the most educated women of her time. Or Claire Clairmont, Mary Shelley's half-sister, who also worked as a governess in Russia.

After the Great French Revolution, many French aristocrats emigrated to St. Petersburg. For example, Pushkin's tutor was a French émigré named Count Montfort, an educated artist and musician, who instilled in the future poet a love of drawing.

Another wave of French tutors swept the country after the Patriotic War of 1812, when many of Napoleon's captured soldiers and officers remained in Russia. One of them was Jean Cape, the tutor of future poet Mikhail Lermontov. Thanks to him and his German nanny, Lermontov became fluent in French and German from childhood.

National fashion

In the 18th century, Germans, who were associated by many in Russia with pedantry, predominated among governesses. But, by the beginning of the 19th century, they were slowly being replaced by the French, who became the most numerous group. They were valued for their easy-going nature, refined manners and "Parisian accent". In fact, the ideal French governess had to be from Paris, have a lively, cheerful character, a flexible mind and manners that enlivened any conversation. French women often had a strong influence on the whole family. Even adults tried to imitate their manners.

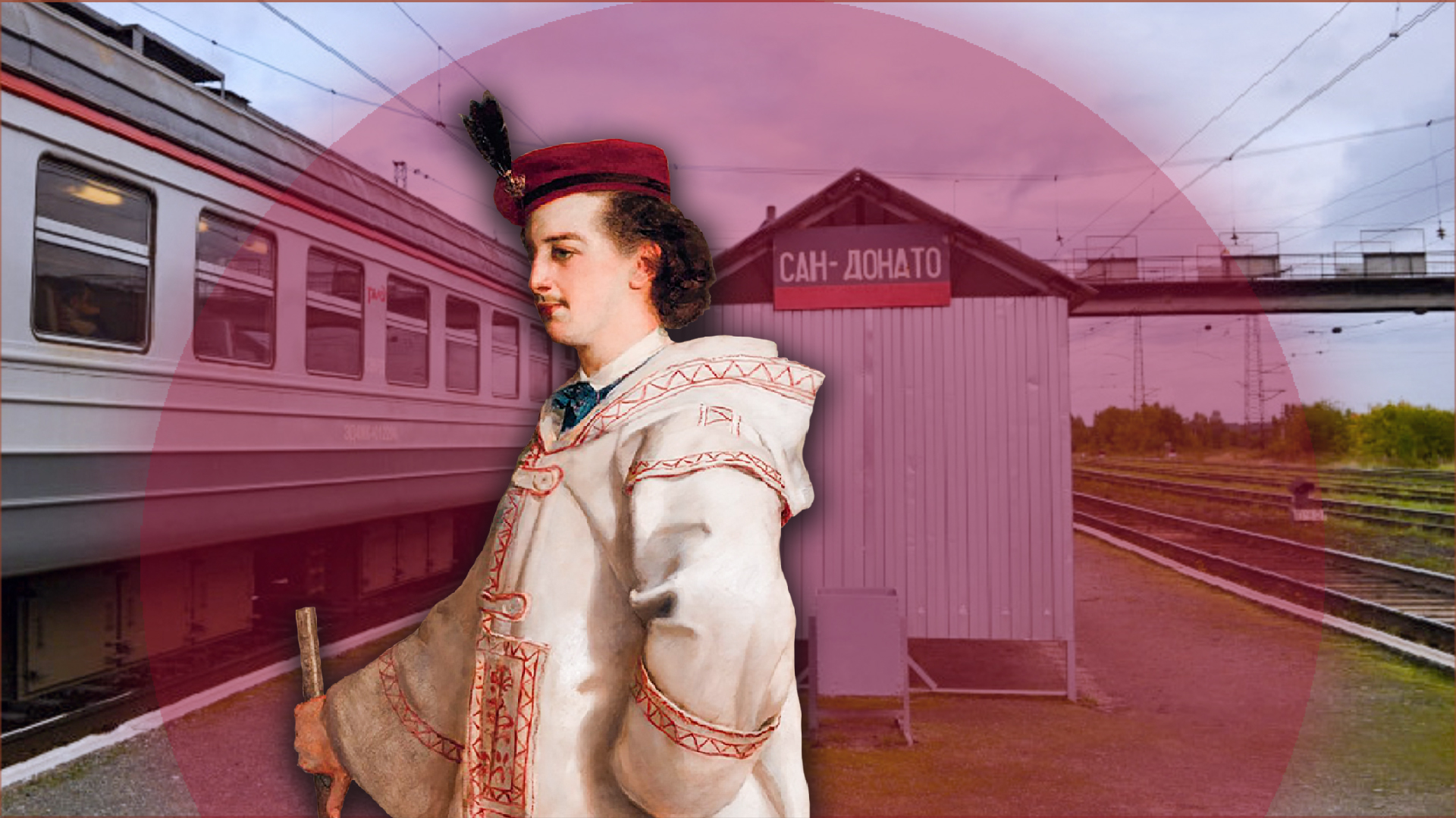

In the 19th century, the Swiss also appeared in the profession. They were considered to be close in qualities to the French, but less refined and more practical. One of them, Pierre Gilliard, was a governess to the children of Nicholas II.

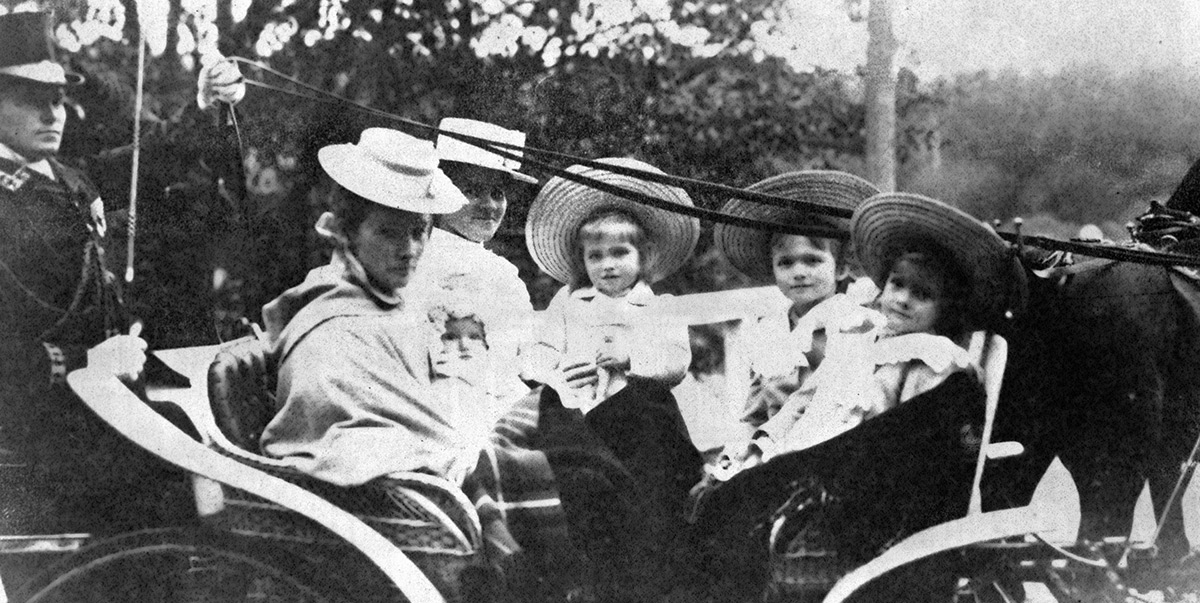

At the same time, English governesses also began appearing, embodying strictness and decency. They were also highly valued for instilling a healthy lifestyle: early rising, walks in any weather, gymnastics and general hardening.

Since the beginning of the 19th century, Russians themselves also began to appear in the profession: The Institutes for Noble Maidens introduced a pedagogical specialization. Later, "learned women" with pedagogical education received at higher courses or at foreign universities joined them. Even young men from impoverished noble families worked as tutors.

Appearance

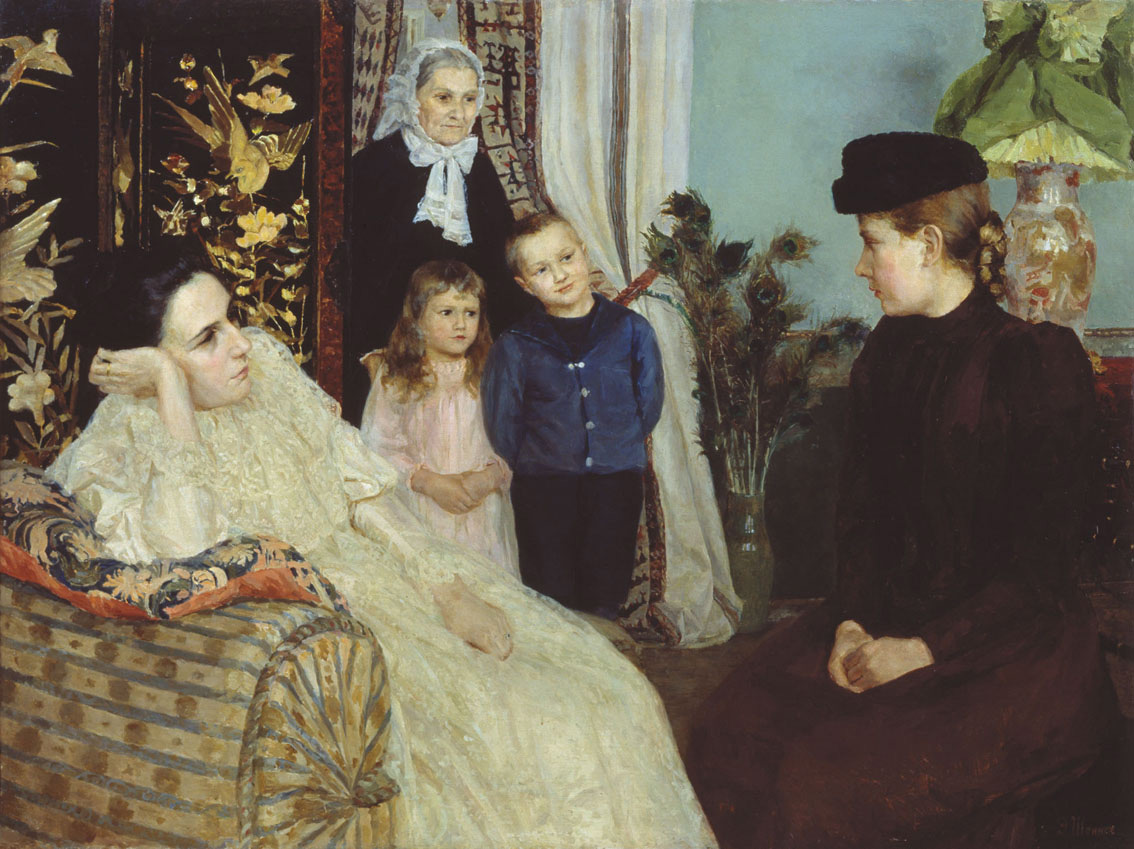

In the selection of tutors and governesses, much attention was paid to age, appearance and marital status to ensure peace in the home.

Youth and beauty were considered a serious drawback, causing concern among fathers and mothers of families. Among governesses, middle-aged women with an unattractive, even ugly appearance (often hunchbacks) were the most valued. Widows with adult children living separately enjoyed the highest trust.

A governess had to dress conservatively, without coquetry, comb her hair strictly and behave in a reserved, but refined manner.

Among the tutors, preference was also given to older, married men. A young and single applicant could only get a job if he was deemed to have a plain appearance. The ideal option was considered to be hiring a married couple: him – with the boys, her – with the girls.

Another of the key conditions for hiring were letters of recommendation from previous employers.

Room, pay & board in the house

The governess would most often live in the children's half: her bed would be in the children's room behind a screen or, less often, in the next room. But, still, in Russia, governesses were treated as members of the family and not as privileged servants (remember Bronte's ‘Jane Eyre’?). Their status was determined by their place at the dinner table: they sat either at the common family table or together with the children in the children's half. Payment depended on the competence of the teacher. Some received quite significant fees. For example, [FIRST NAME] Bruckner, the tutor of the princes Kurakin, received 35,000 rubles for 14 years of work, [FIRST NAME] Granmont, the tutor of the princes Dolgoruky – 25,000. Englishman [FIRST NAME] Windson, the tutor of the Uvarovs and Lermontov, meanwhile, received 3,000 rubles a year and lived in a separate outbuilding.