What did Arabs do under the Russian emperors?

The first ‘Araps’ or ‘Arapchats’ (a Turkish term for an Arab person or someone from the Arabian Peninsula, the latter often referred to children and teenagers) appeared in Moscow in the 17th century. They were mostly exotic “gifts” from Eastern embassies or European diplomats hoping to impress the tsar. The situation changed, however, with Russia's transformation into an empire. Peter the Great, eager to integrate the country into the pan-European cultural code, adopted many of the fashionable attributes of European monarchies. The ‘Black Pages’ were among them. Peter commissioned foreign artists (such as Adriaen Schoonebeck) to create a series of portraits depicting the tsar next to a Black boy. These images set a standard of prestige. Soon, having one's own "black boy" (real or depicted in a portrait) became fashionable among the upper classes – a sign of proximity to the throne, wealth and familiarity with Western customs. Empresses Catherine I, Elizabeth Petrovna, as well as future Emperor Paul I are depicted in formal portraits accompanied by Black servants. Empress Anna Ioannovna also has a sculpture depicting a black boy presenting her with an orb.

Paul

Paul

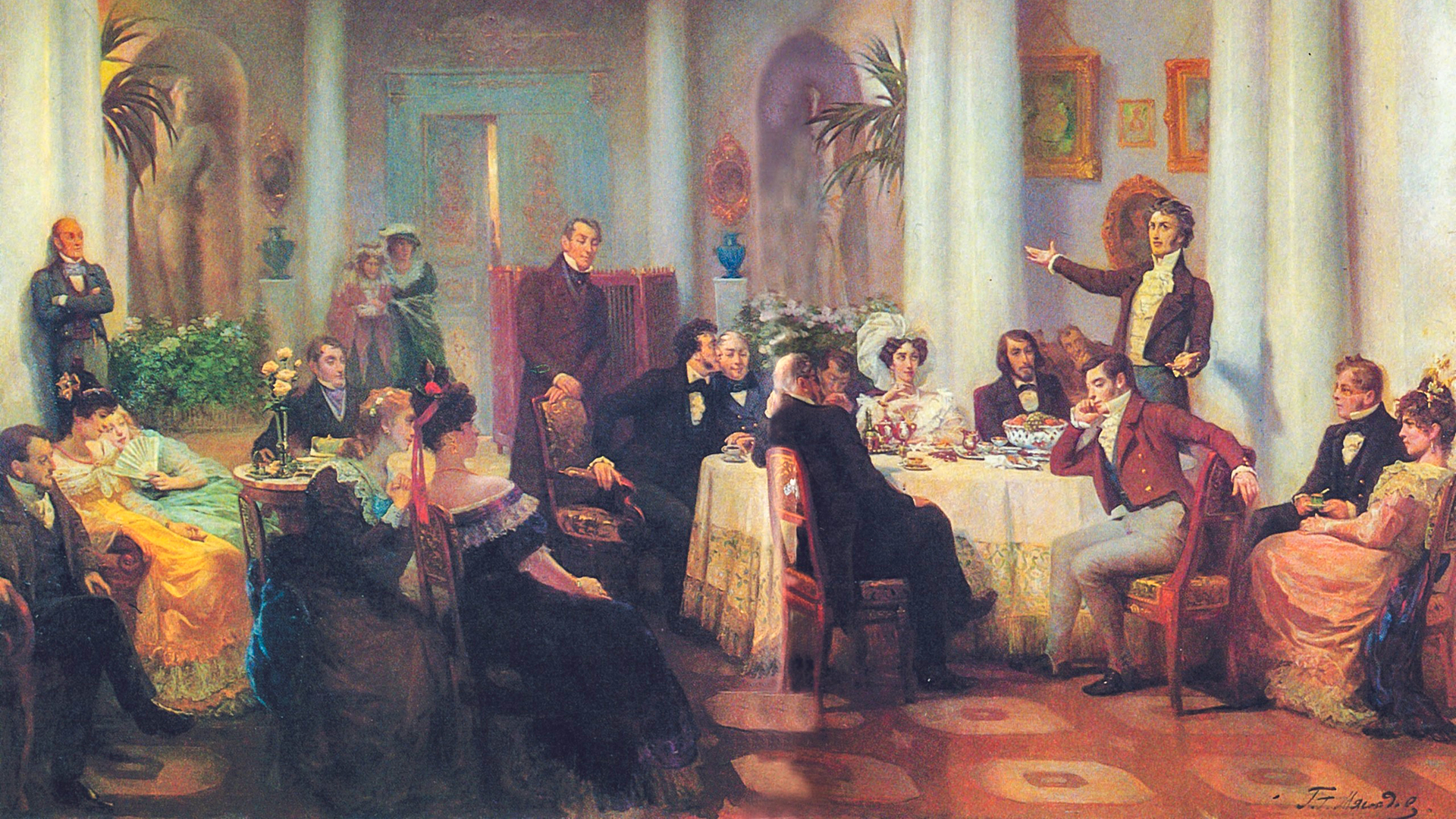

The status of court blacks was quite high. They were officially hired workers, awarded ranks and paid a fixed salary that could reach 600-800 rubles per year, a significant sum at the time. The Arabs' costumes were works of art: scarlet or blue trousers, gold-embroidered jackets, snow-white turbans with ostrich feathers or oriental caps. The cost of such attire could equal the entire annual salary of a mid-level official.

Araps typically lived at the palace and were taught the Russian language and literacy. Their main function was to create an imperial glamour. Araps accompanied the emperor on his visits, opened doors and participated in court masquerades. And conversion to Orthodoxy was a mandatory requirement for service at court.

Catherine I

Catherine I

The most striking example of the unique opportunities this service afforded was the fate of Abram Petrovich Gannibal, "Peter the Great's Arab". Having received an excellent education, built a distinguished career as a military engineer and risen to the rank of general, he shattered the notion that Araps at court were mere decoration. His story became a legend, later immortalized by his great-grandson, poet Alexander Pushkin.

Ceremonial costume of a court Moor. St. Petersburg, workshop "I. P. Lidval and Sons", late 19th – early 20th century. The State Hermitage Museum

Ceremonial costume of a court Moor. St. Petersburg, workshop "I. P. Lidval and Sons", late 19th – early 20th century. The State Hermitage Museum

By the 19th century, the staff of the Court Moor (later, ‘His Majesty's Own Moors’) was strictly regulated. Their number ranged from eight to a maximum of 20. Candidates were carefully selected: dark skin, tall stature and a distinguished appearance were all required. Often, dark-skinned sailors from ships calling at Russian ports or children of mixed marriages applied for the position of Court Moor.

This is a portrait of Peter the Great, Tsar of Russia (1672–1725), and his page boy

This is a portrait of Peter the Great, Tsar of Russia (1672–1725), and his page boy

The figure of the Moor survived several reigns. Until the early 20th century, their appearance at official receptions and balls was considered particularly chic. Memoirists noted that the empty doors of palaces, with no one left to ceremoniously open them, became a metaphor for the end of the era of imperial pomp.