What Russian classic writers thought about SNOW

Bring Back Spring

“The weather outside is vile: some kind of filth is falling down from the sky in huge quantities and forms a slush on the ground that neither runs off like rain nor piles up like snow, but turns all the streets into one big puddle,” fumed Korney Chukovsky.

Poet Pyotr Vyazemsky, meanwhile, felt much the same: “Cold again; yesterday something was falling from the sky — some say hail, some snow, some sleet — but, whatever it is, it’s disgusting,” he complained to historian Alexander Turgenev.

“Wet snow underfoot. And, in general, it feels like you’re walking along the first — unfortunately very long — landing of a dark staircase. And the sky above you looks as if it’s behind that dull, rippled glass they install in the lavatories of international train cars,” writer Vsevolod Ivanov sadly noted in his diary.

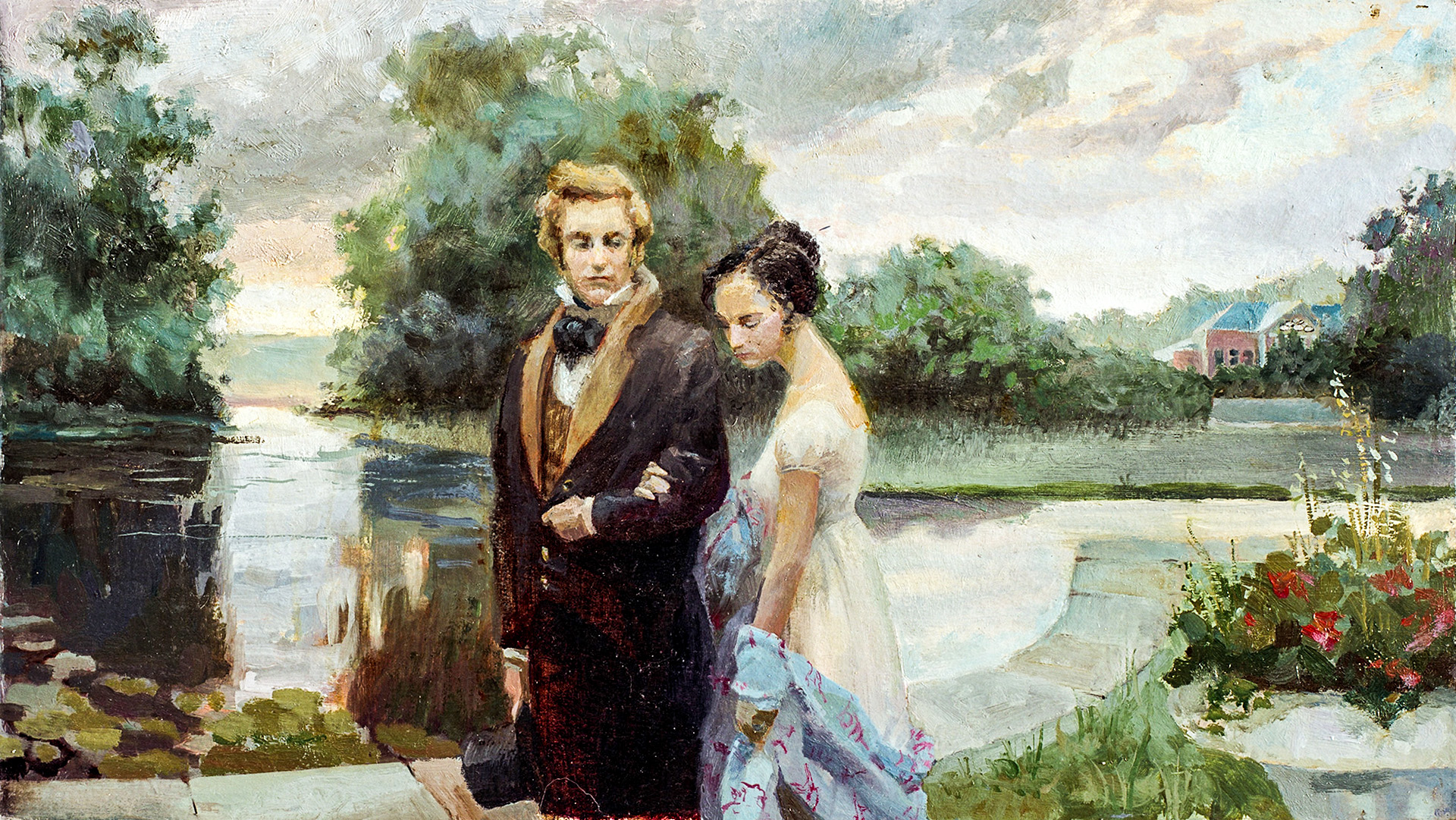

For Ivan Turgenev, author of ‘A Nest of the Gentry’ and many other novels, the familiar winter snowstorms provoked genuine anger: “A snowstorm has been raging since early morning — crying, groaning, howling in the bleak streets of Moscow; the branches of the trees outside my windows intertwine and writhe like sinners in hell and through all this noise comes the mournful ringing of bells… What weather! What a country!”

Anton Chekhov loved the warm Crimean winters and, when staying in Melikhovo near Moscow, never tired of complaining about the whims of the weather. “Our weather is outrageous. Today, for instance, at six in the morning, there was frost, a clear sky, the sun was shining and everything promised a fine day; but now, at eight in the morning, the sky is already covered with clouds, a north wind is blowing and it smells of snow. There is still a great deal of existing snow; travel is only possible on wheels and even then, with adventures… Cold! It’s boring without good weather,” he complained to publisher Nikolai Leikin.

Snow Inspires

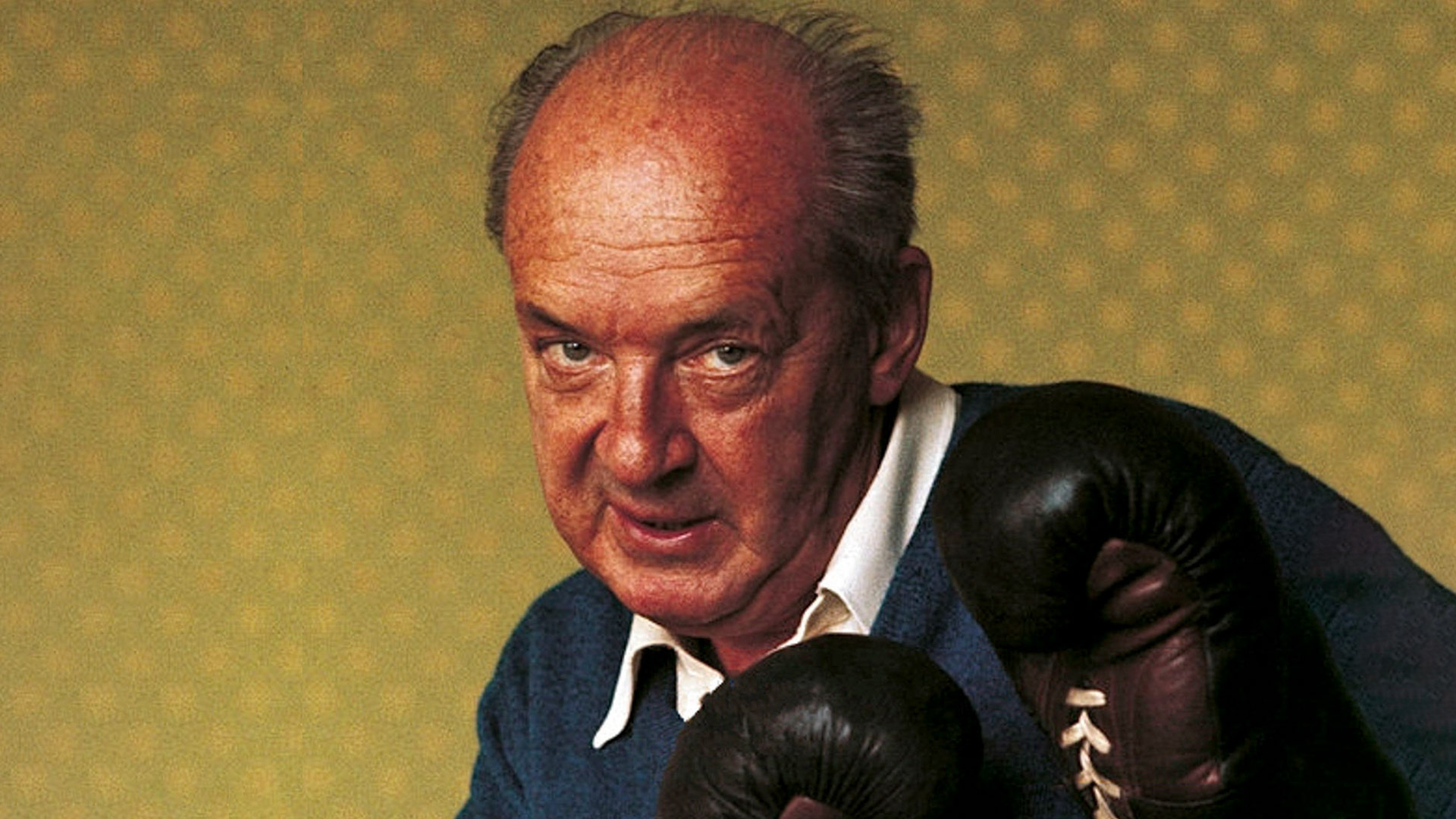

Precipitation doesn’t just drive people into seasonal depression, it also forces them to change plans. “At last, snow has fallen. I feel like going to Moscow – to wander about…” Chekhov once wrote to publisher Alexander Suvorin.

“I’m going to Moscow, as soon as I have money and there’s snow. The snow is falling, but money doesn’t fall from the sky,” Alexander Pushkin wrote to writer Ivan Velikopolsky.

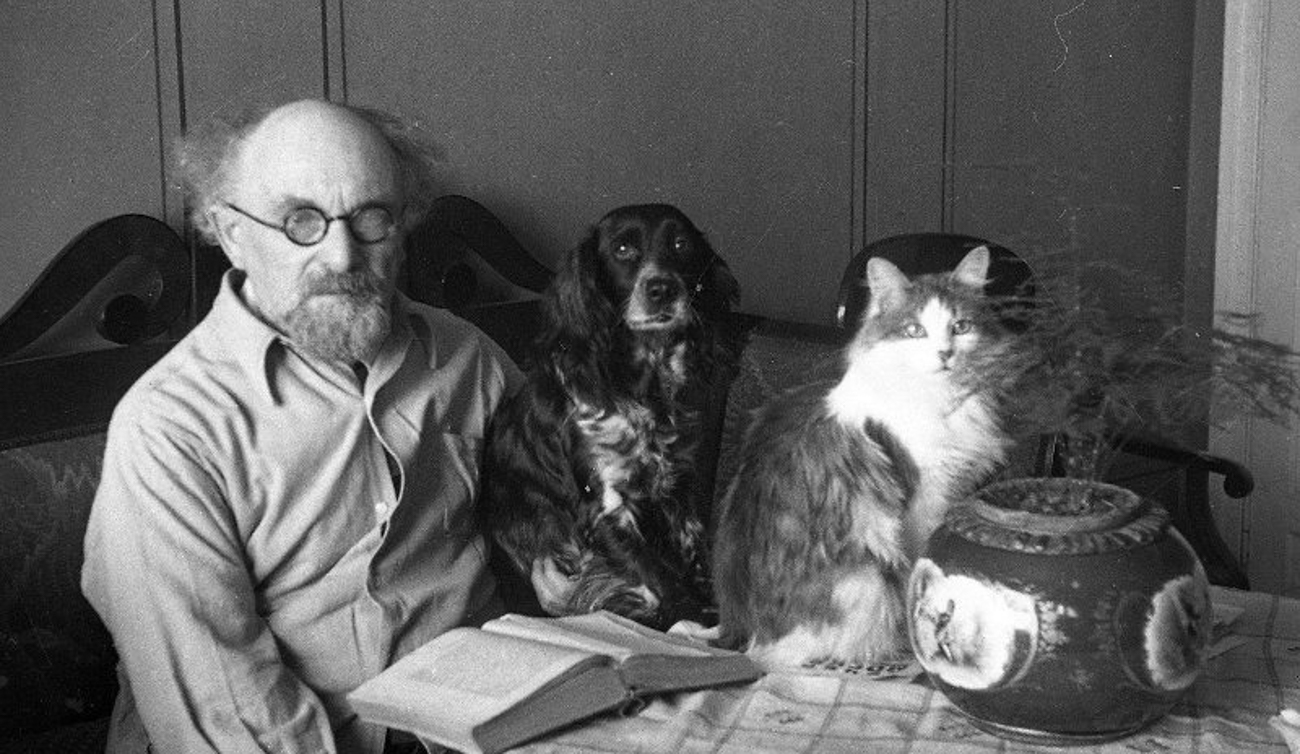

Leo Tolstoy sometimes stayed home without regret, working on another manuscript: “The weather is nasty, snow. I dictated and wrote ‘Youth’, with pleasure to the point of tears. Spent the whole day at home.” At other times, he simply chose rest: “Snow. Went hunting. A blizzard. I saw nothing. I did nothing all day.”

For poet Alexander Blok, a snowstorm became a source of inspiration: in the swirling snowdrifts, he once spotted a bright spot – an image that prompted him to create ‘The Twelve’.

“Have you ever walked through city streets on a dark night, in a blizzard or rain, when the wind tears and buffets everything around? When snowflakes blind your eyes?.. The wind swings the heavy hanging lanterns with such force that it seems they’re about to break loose and shatter to pieces. And the snow whirls ever more fiercely, flooding the snowy columns. The blizzard has nowhere to go in the narrow streets; it rushes about in all directions, gathering strength to burst into open space. But there is no open space. The blizzard spins, forming a white veil through which everything around loses its outlines and seems to blur.”

There Is No Bad Weather

“On the evening before last, rain fell on the fresh snow and then, overnight, turned into snow again. In the morning, the thermometer stood at zero and everything depended on that moment: if it had gone any higher, everything would have melted, but it went down and, by evening, reached –5°C. And the snow kept falling without pause and, today, Moscow lies under fluffy, white, untouched snow, reviving some unprecedented charm of old Moscow,” writer Mikhail Prishvin recorded in his diary about the beginning of winter in 1952.

And despite all the disdain from his peers, Leo Tolstoy was delighted by a winter day: “Went by tarantas to Shchelkunovka, then, from there, on horseback. Snow. Despite everything, twice such a feeling of joy came over me that I thanked God!”