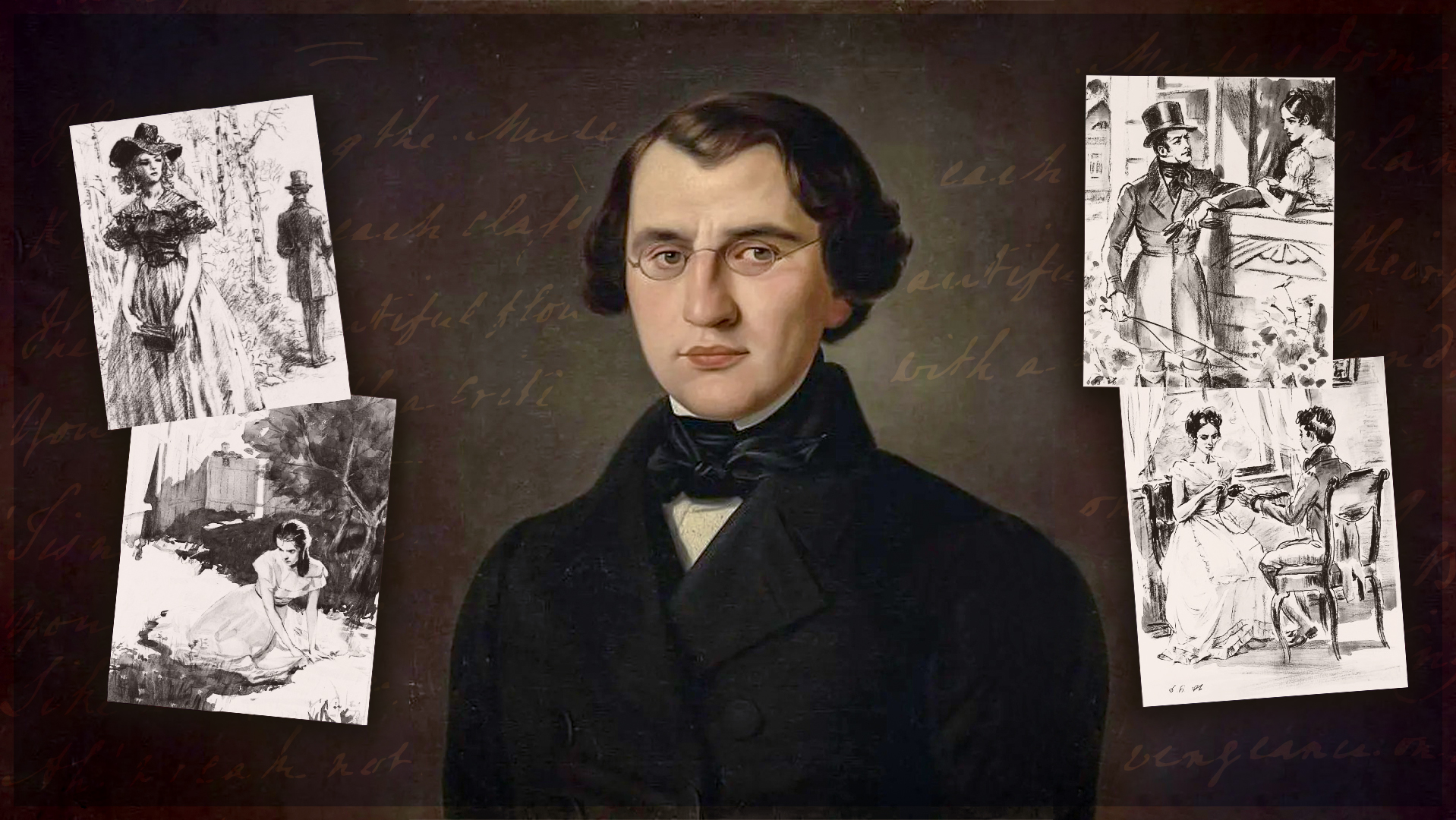

Why did Europe & Asia fall in love with the ‘Russian La Fontaine’?

‘The Crow and the Fox’, ‘The Swan, the Pike and the Crayfish’, ‘The Dragonfly and the Ant’, ‘The Quartet’, ‘The Monkey and the Glasses’, ‘The Elephant and the Pug’, ‘The Wolf and the Lamb’ – for three centuries now, ‘Grandfather Krylov’ has been teaching young readers the basics of morality and ethics through his fables. Quotes from his works are firmly ingrained in the memory of most native Russian speakers, if not with the porridge of early childhood, then with a pie from the school cafeteria.

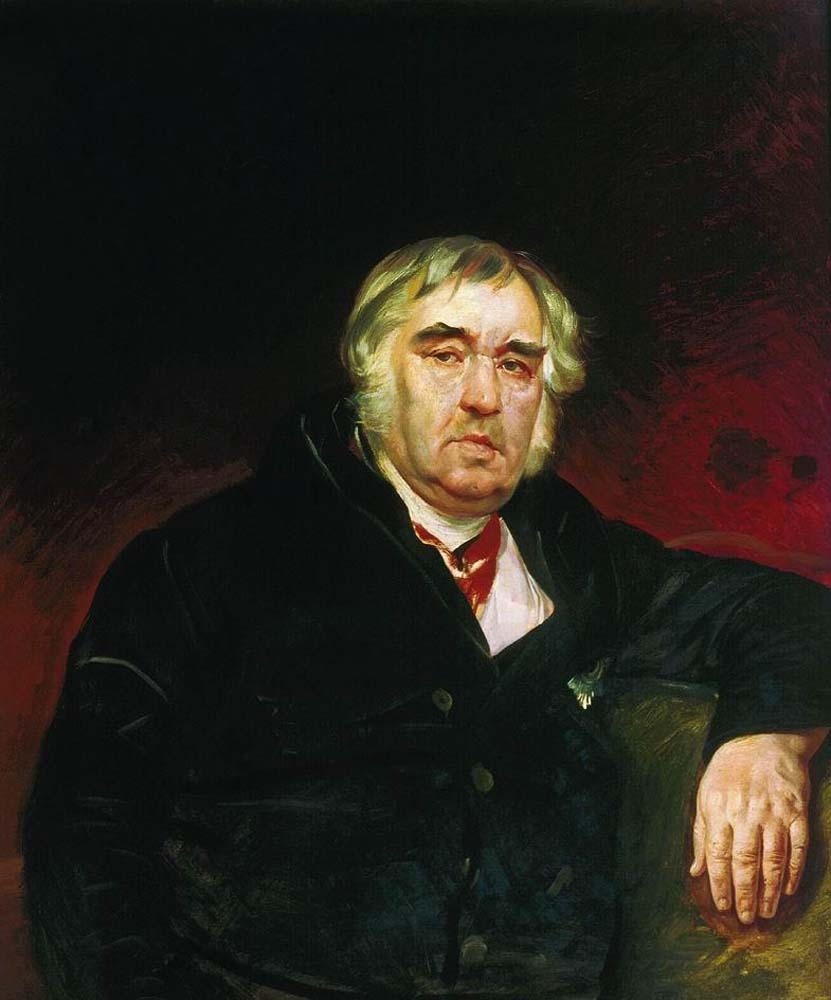

The kind, languid fat man in a velvet frock coat from Karl Bryullov's portrait, the slovenly glutton dozing off while visiting – in the second half of his life, Krylov consciously cultivated the image of an eccentric, working on a legend. However, this ostentatious simplicity was combined with encyclopedic knowledge, brilliant conversational skills and extensive, not always pleasant, life experience.

Valentin Serov. Illustration for the fable "The Crow and the Fox"

Valentin Serov. Illustration for the fable "The Crow and the Fox"

A Difficult Childhood

Turmoil accompanied Ivan Krylov almost from infancy. He came from impoverished noble families and was the eldest son of an army captain. In 1772, his father was sent to suppress the Yemelyan Pugachev uprising. Little Ivan and his mother followed him to the town of Yaitsky, but, due to the danger, they were transferred to Orenburg. Soon, this city was also under siege. Pugachev vowed to hang not only Captain Krylov but his entire family, including his son. These events left a deep impression on the child and would resonate repeatedly in his adult life.

After the suppression of Pugachev's rebellion, Krylov's father, having received no awards, retired and moved the family to Tver, where he took the modest position of chairman of the provincial magistrate. He died soon after. Eleven-year-old Ivan became the eldest male member of the family (he had a younger brother, Lev) and the sole breadwinner, taking a job as a sub-clerk in the same magistrate’s office. He learned to read and write at home from neighboring landowners, who allowed him to attend French lessons with their children. From his father, he inherited a chest of books – classics, satirists and philosophers – which became the foundation of his self-education.

In 1782, the widow and her sons moved to St. Petersburg to apply for a pension. Ivan, meanwhile, was appointed a clerk in the Treasury Chamber. But, a career in government service did not appeal to him. He became fascinated with the theater and, at 15, wrote the libretto for the comic opera ‘The Coffee House’, peppered with idioms he'd picked up and overheard. At 18, he left the service, deciding to live by writing. However, the tragedy ‘Philomela’ and the comedies ‘The Mad Family’ and ‘The Pranksters’ were unsuccessful.

At the same time, he continued to educate himself: fluent in French, he began studying Italian, German and, later, Ancient Greek, poring over the originals of Homer and Aristophanes. His erudition, mathematical talent and violin playing impressed his contemporaries.

Valentin Serov. Illustration for the fable "Quartet"

Valentin Serov. Illustration for the fable "Quartet"

A Rebellious Youth

He found his niche in magazine satire. In 1789, he began publishing the monthly ‘Mail of Spirits’, in which, using correspondence between gnomes and a wizard, he sarcastically mocked officials for their tyranny, bribery and ostentation. The magazine lasted less than a year, had only 80 subscribers, but attracted the attention of the authorities. Legend has it that Catherine the Great invited him to "travel at public expense", meaning leave the capital.

The satirist didn't give up and, three years later, with friends, founded a printing house and the magazine ‘Spectator’, followed by ‘The St. Petersburg Mercury’ (1793), in which he continued to ridicule the authorities and nobility. This resulted in a personal audience with the empress. The magazine was closed and Krylov was effectively banned from publishing. Then, he left St. Petersburg.

1794-1806 was the strangest period of his life. He lived on the estates of acquaintances and served as secretary and tutor to the children of Prince Golitsyn. For several years, he immersed himself in the world of professional card games, traveling to various fairs. According to some reports, he was even banned from entering both capitals, due to gambling. These years spent "at the bottom" gave him a unique experience, which he later applied to literature.

In 1806, Krylov returned to St. Petersburg with three translations of La Fontaine's fables, a long-time admirer. Fabulist Ivan Dmitriev approved of them, saying: "This is your true lineage." That same year, his comedies ‘The Fashion Shop’ and ‘A Lesson for Daughters’, both scourging Gallomania, were successfully staged. But, from 1808 onward, he focused exclusively on fables.

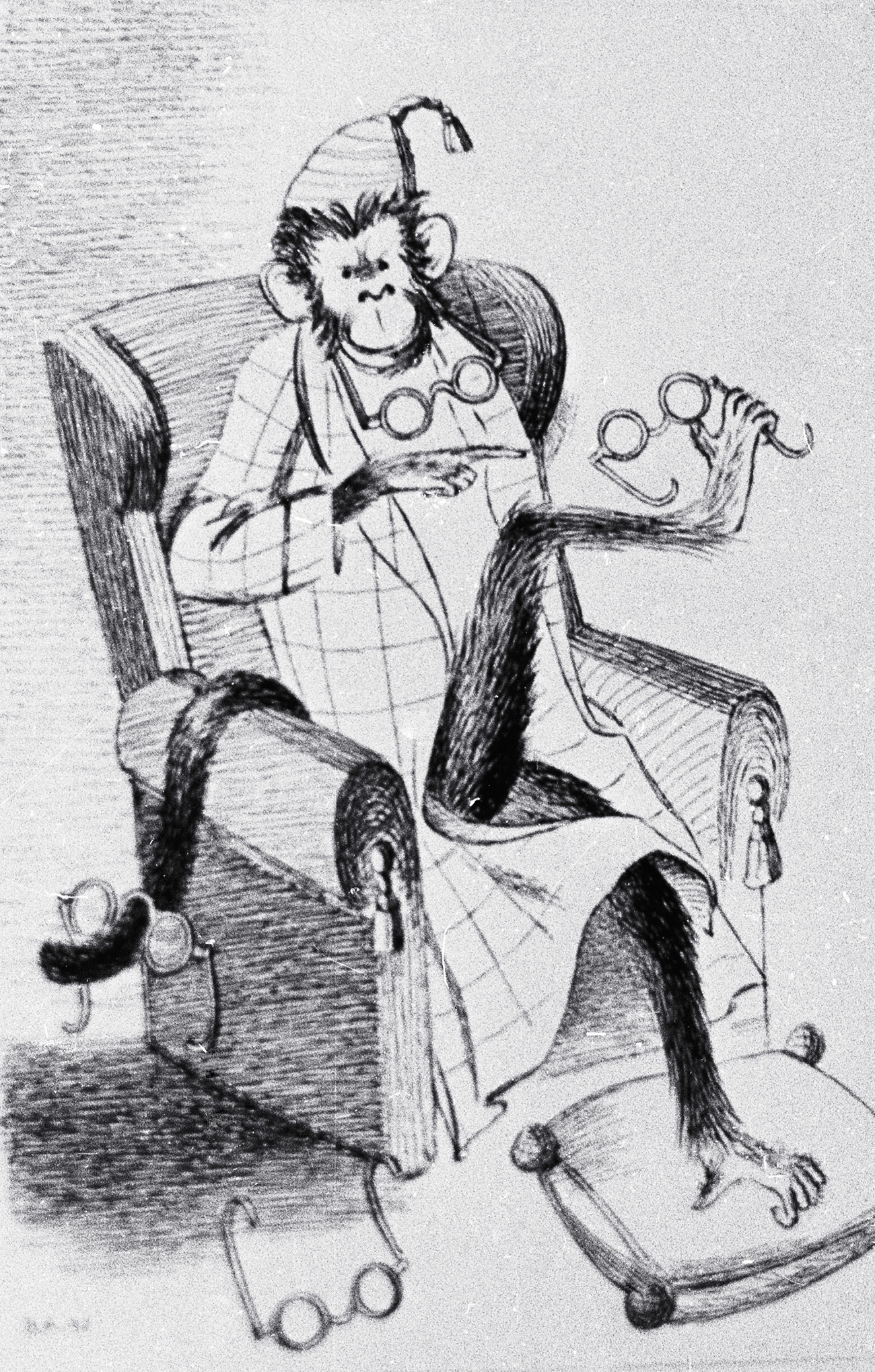

Nathan Altman. Reproduction of an illustration for the fable "The Monkey and the Spectacles"

Nathan Altman. Reproduction of an illustration for the fable "The Monkey and the Spectacles"

‘Grandfather Krylov’

A year later, his first slim book containing 23 fables was published. Its success was astonishing. Krylov revolutionized the fable, transforming it from a conventionally allegorical one into a short comedy or drama with vivid characters, brilliant vernacular and a poignant social subtext. ‘The Elephant and the Pug’, ‘The Quartet’, ‘The Swan, the Pike and the Crayfish’ – these catchphrases instantly became popular.

In 1812, he joined the Imperial Public Library as an assistant librarian and served there for nearly 30 years, working on bibliography. He was now a respected writer, favored by authorities. His fables, especially those from the wartime era (‘The Wolf in the Kennel’, which was associated with Kutuzov), became national treasures.

Karl Bryullov. Portrait of the fabulist I.A. Krylov. 1839

Karl Bryullov. Portrait of the fabulist I.A. Krylov. 1839

He never married officially. For many years, his common-law wife was a cook named Fenya (Fekla Ivanova), who bore him a daughter, Alexandra. Krylov provided her with an education and a dowry and left his entire fortune to her family. He was elected a member of the Russian Academy and awarded a gold medal in 1823. In 1825, Russian-Parisian Count Grigory Orlov self-published a two-volume collection of Krylov's fables, translated into French and Italian by 59 poets. This was followed by new translations into all major European languages, including Danish, Polish, Romanian and others.

Krylov died on November 21, 1844, of double pneumonia. His funeral was magnificent. In his memory, Krylov ordered copies of his final, ninth edition to be sent to all his friends. His monument, designed by Pyotr Klodt (1855) in the Summer Garden in St. Petersburg, is surrounded by figures of his fables' heroes, embodying the sage's eternal dialogue with the people.