Who was the creator of the ‘Russian’ salad?

In the West, this dish is called ‘Russian’ salad, but, in Russia, it’s known by the last name of its creator, Lucien Olivier. His life, however, is shrouded in mystery. Some even believe he never existed at all: not a single portrait or letter of Mr. Olivier has survived.

Anna Kruglova

Anna Kruglova

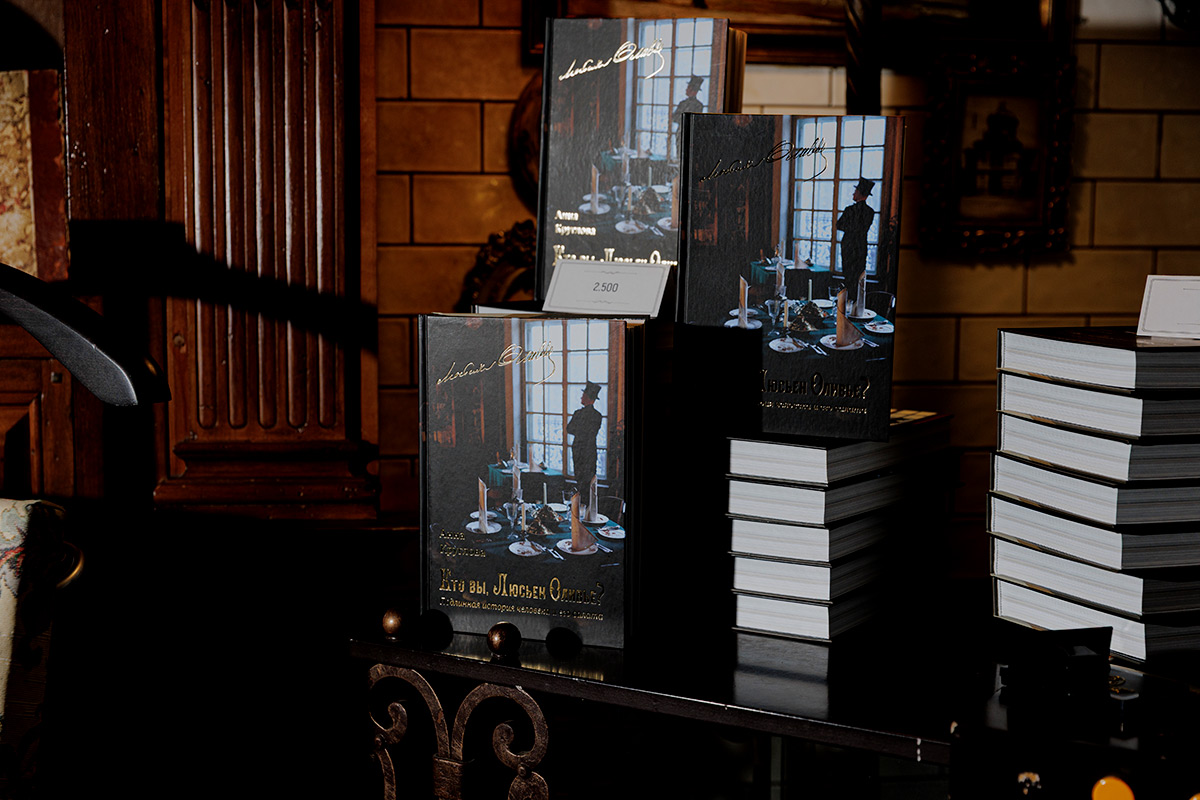

Journalist Anna Kruglova set out to unravel the mystery of the life of the legendary salad’s creator. She spent many months in archives, visited his former Moscow addresses and even found his telephone number. Anna shared all her discoveries in her book ‘Who Are You, Lucien Olivier?’

1. A Moscow Frenchman

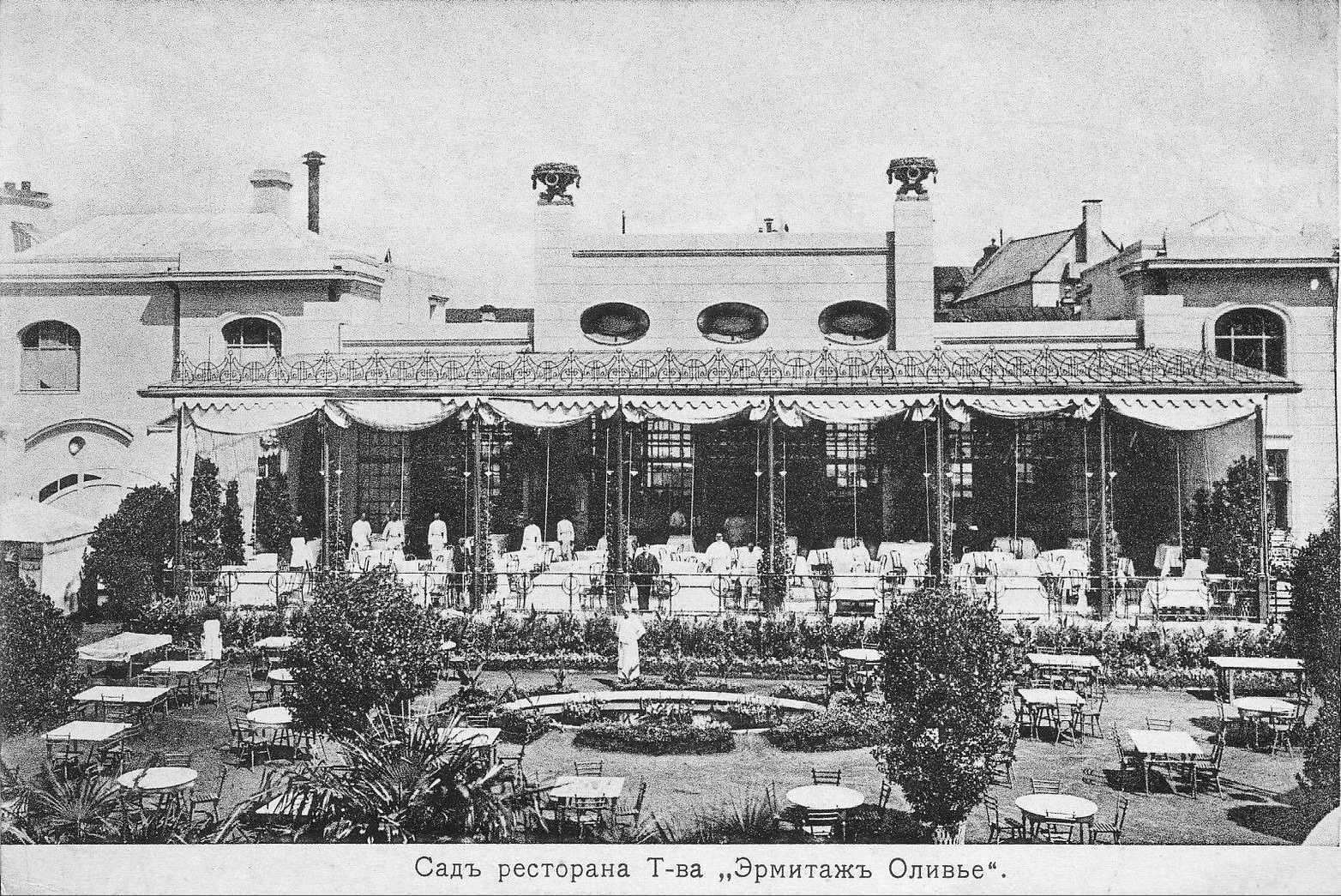

The ‘Hermitage’ restaurant, circa 1900-1901.

The ‘Hermitage’ restaurant, circa 1900-1901.

Lucien Olivier was allegedly born in Moscow on March 14, 1837. He was the son of a French hairdresser, who also ran a shop selling "fashionable items" on Petrovka Street. At that time, many French people were going to Russia, fleeing the 1830 revolution. Olivier's godfather was another Moscow Frenchman – a close friend of his father, Troquville (or Tranquille) Yar and the owner of the cult ‘Yar’ restaurant. Apparently, this determined young Olivier’s choice of profession.

2. Moscow's leading restaurateur

Iinside the 'Hermitage', the beginning of XX century

Iinside the 'Hermitage', the beginning of XX century

In the 1860s, Olivier took the helm of the ‘Hermitage’ restaurant on Neglinnaya Street. French cuisine was very popular among Russian nobles and bourgeois at the time and Olivier, as it turned out, had a real talent for management. "In the 19th century, French chefs in Russia were not just in demand – they shaped gastronomic fashion itself," writes Anna.

Under Olivier's leadership, the ‘Hermitage’ came to be considered a truly luxurious establishment. The entire Moscow elite dined there. Olivier himself took orders for large dinners and oversaw not only the preparation of dishes, but also cared for the restaurant's atmosphere. "The kitchens in the busiest Parisian restaurants are mere closets compared to these vast and lofty halls," writes Anna, quoting ‘Hermitage’ regular, publicist Pyotr Boborykin.

3. He had a telephone number

The ‘Hermitage Olivier’ hotel.

The ‘Hermitage Olivier’ hotel.

Telephone service came to Moscow in 1881. At the time, having a phone at home or in an office was a true luxury. The cost of maintaining this technical innovation was comparable to renting an apartment! Yet, despite this, Olivier’s ‘Hermitage’ restaurant had one of Moscow's first telephone numbers.

4. Managed the buffet for the coronation of Alexander III.

"The Hermitage"

"The Hermitage"

In May 1883, celebrations for the coronation of Emperor Alexander III were held in Moscow. Lucien Olivier was in charge of the culinary part of the Moscow celebration in Sokolniki: the city's mayor personally asked him to do it.

Olivier had to arrange buffets and service for both the imperial family and the visitors of Sokolnik. He proposed the menu, table settings and staff uniforms. Furthermore, the ‘Hermitage’ restaurant became something of a press center for French journalists during that period.

And although there were many enthusiastic reviews about the refreshments, the press did not contain a single comment from Olivier himself.

5. Mysterious death

His grave in Moscow.

His grave in Moscow.

He died literally at the peak of his career, on November 14, 1883. It happened in Yalta, Crimea. The cause of death was listed as "heart disease". Olivier was only 46 years old.

However, the day before, he had been elected to the board of directors of the ‘Hermitage Olivier’ hotel and, a week earlier, as it turned out, he had sold his house in Moscow. According to Yalta local historians, writes Anna, Olivier planned to open a restaurant at this famous Black Sea resort. There is no precise data on this nor on what exactly happened that day.

He was buried in Moscow at the Vvedenskoye Cemetery and his grave has been preserved. By the way, Moscow tour guides often tell the legend that culinary students visit his grave seeking culinary wisdom.

6. The secret of the ‘Russian’ salad

The building of "The Hermitage" now is the home for the theater.

The building of "The Hermitage" now is the home for the theater.

The most mysterious thing: there was no ‘Olivier’ salad on the ‘Hermitage’ restaurant menu; there were no salads at all, only appetizers! However, other Russian restaurants had "salade olivier", specifically spelled with a lowercase letter, as a common noun.

Most likely, Anna concludes, the visitors themselves called one of such dishes "salade olivier".

Abroad, this salad is more prominently known as ‘Russian’. Recipes under this name can even be found in 19th-century cookbooks. The most famous example is the 1846 books by Charles Elmé Francatelli, chef to Queen Victoria of England.

Olivier himself left no exact description of his signature dish. Judging by the recollections of his guests, it was an appetizer with hazel grouse, crayfish tails and Provençal sauce. Many tried to replicate it, but no one surpassed the original.

7. Soviet revival

After Olivier's death, the restaurant continued to operate and offer all the same signature dishes. Even after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, a public catering establishment for workers was located in the building. It’s likely that old school chefs or, at least, their students continued to work there. However, the recipes were simplified to make the dishes more widely accessible. And ‘Olivier’ salad gained nationwide popularity, thanks to the publication of the recipe in all Soviet cookbooks and newspapers.