How a British aristocrat fell in love with Russia & taught the entire kingdom to love it

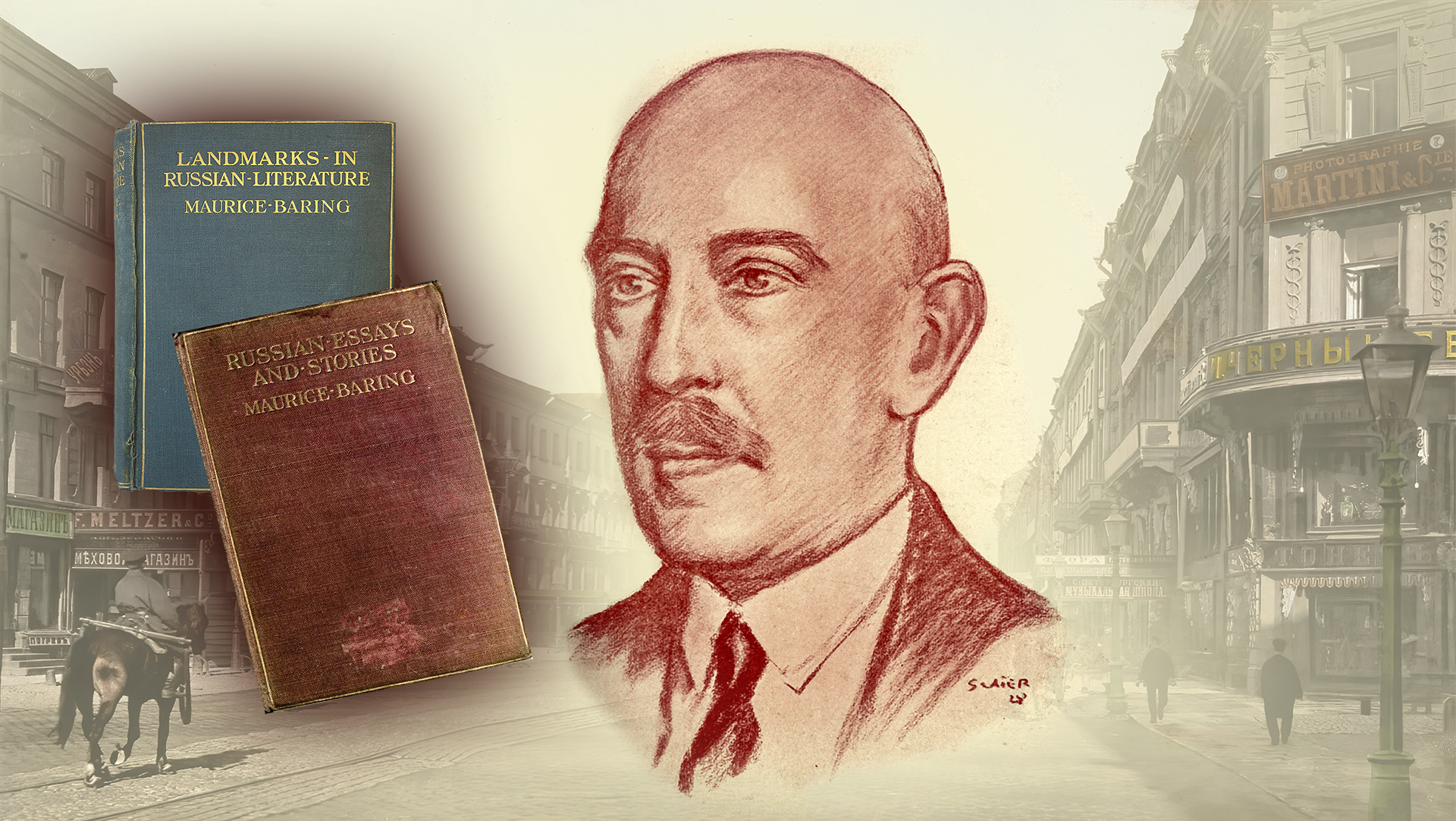

Maurice Baring spent several years in Russia and wrote several works about his observations. He is the man who “infected” H. G. Wells and Gilbert Chesterton with Russophilia.

He was born on April 27, 1874, in London. Lord Revelstoke, the future publicist's father, was the head of ‘Baring Brothers’, London's oldest bank, which held accounts for the Russian government. Maurice's uncle, meanwhile, was Constable of Windsor Castle, so, as a child, he would sit on the lap of Queen Alexandra – the sister of Empress Maria Feodorovna, wife of Russian Tsar Alexander III.

Maurice received an excellent education: He graduated from Eton College and then Trinity College, Cambridge. From 1898, he served as a diplomat in Paris, Copenhagen and Rome. However, he soon left the diplomatic service, began to travel and tried his hand at journalism. In 1904, he became a correspondent for ‘The Morning Post’ newspaper and, with the start of the Russo-Japanese War, was sent to the theater of war. The result of this assignment was the book ‘With the Russians in Manchuria’ and a passionate desire to learn more about these fascinating people.

He soon returned, immersed himself in the culture and mastered the language. The language was essential; Baring could not tolerate being dependent on translators. He quickly realized that "for one who speaks Russian and for one who does not speak Russian, there exist two absolutely different Russian peoples." For the next seven years, Baring lived between the two countries, although it seems his Russian periods lasted longer than his British ones. He lived most often at the Benckendorff estate in the village of Sosnovka – Baring had become close to the family of Russian ambassador Alexander Benckendorff during his diplomatic service in Copenhagen. The Benckendorffs, in turn, introduced Maurice to many prominent people. This is how writer Nina Berberova remembered him: "Baring is a remarkable figure, the kind that could only have emerged in England and only in the stable world of the early 20th century. Everyone loved him and he loved everyone; he was everywhere and everyone knew him. He simply adored the family of the Russian ambassador Alexander Konstantinovich and not only the ambassador himself, <…> and Countess Sophia and their adult sons, Konstantin and Peter, but also the ambassador's brother, Count Pavel Konstantinovich, the Hofmarshal and Minister of the Court."

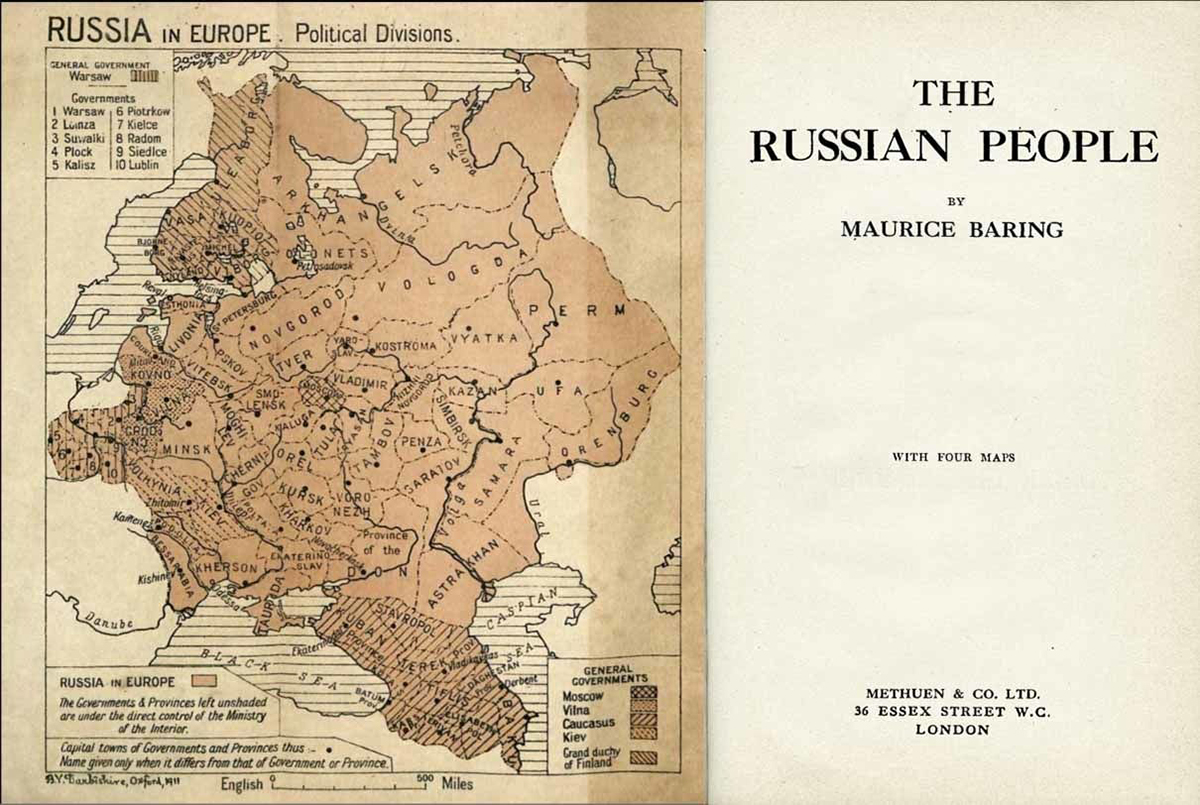

M. Baring's book "Russian People". 1911.

M. Baring's book "Russian People". 1911.

However, Baring did not only shine in the drawing-rooms of the Russian aristocracy; he penetrated all layers of society. Introducing himself as ‘Mauriky Eduardovich’, he talked to policemen, cab drivers, janitors and mingled with doctors, teachers and lawyers. For ‘The Morning Post’, Baring wrote reports on the work and dissolution of the Duma, essays on the turbulent political life of St. Petersburg, as well as literary reviews. For example, Baring was the first to tell the English about Chekhov in detail. In 1907, his articles on Russian life were published as a separate book, ‘A Year in Russia’.

In 1910–1911, two books by Baring were published in succession: ‘An Outline of Russian Literature’ and ‘The Russian People’. In the first, he introduces the English reader to the most brilliant Russian classics. The second book is, in essence, a commentary on the first. It’s impossible to understand Russian literature without understanding the nature of the Russian character. The Englishman thoroughly explains to his compatriots what Russian gaiety is and how it manifests in Gogol's work, tells where Turgenev's weak but enthusiastic natures come from, what depths are hidden in Chekhov's unremarkable characters and why they are so ironically sad. And, of course, he speaks of the abysses revealed by Dostoevsky.

H.G. Wells (sitting in a sleigh) and Maurice Baring (standing center) in the winter of 1914 in the village of Vergezha in Novgorod province, visiting the Narodnaya Volya member A.V. Tyrkov.

H.G. Wells (sitting in a sleigh) and Maurice Baring (standing center) in the winter of 1914 in the village of Vergezha in Novgorod province, visiting the Narodnaya Volya member A.V. Tyrkov.

But, his main book was the work ‘What Russia is Driving At’, published in 1914. In it, Baring touches upon almost all spheres of Russian life. He opens the work with a historical excursus, describes the Russian peasantry, talks about the life of the upper classes, explains the phenomenon of the Russian intelligentsia, elucidates how the state system is structured and where revolutionary sentiments come from, gives an idea of Russian education, the church, the judiciary and, finally, confesses his love for Russia.

The book feels, somewhat, like a farewell to Russia. That is probably why the last chapter, ‘The Spell of Russia’, seems the saddest. The author seems to sense that his parting from Russia is inevitable. And so it happened. In 1912, Baring set off on a round-the-world trip; in 1913, as a correspondent for ‘The Times’, he traveled to the battlefields of the Balkan War. His last visit to Russia was in 1914, when he accompanied his writer-friend H. G. Wells on a trip to St. Petersburg. After the Bolsheviks came to power, Baring never returned to Russia.

The full article (in Russian) can be found on the ‘Russkiy Mir’ website.